Thunderheads marched over the Red Rock Jewel Valley. Out in front, the raindrops of the vanguard splattered slowly at first, making earthy brown splotches on the red sandstone. Milarepa felt the first drops on his neck and looked up, surprised to see clouds marshalling overhead. Rain was scarce here. Praise Indra, he thought, and went back to collecting twigs from the tangle of grass beneath a clump of stunted cedars. Then came a thunderclap which resounded between the valley walls and the rain thickened into a sheet. He stood upright to look again. A wave of dizziness came over him and blurred his vision. His observance of the ascetic rites had left him haggard and emaciated. When his vision returned his stomach dropped as the great column of storm heads came into focus. A billowing mass of black clouds which rose for miles and miles and filled the entire sky. They crept above the river bed, beating their thunderous war drums and flashing their standards of brilliant lightning for all to see. This was no benevolent shower brought forth from the grace of the rain god.

Suddenly, a ghastly wind came ripping through the valley. The patter of the raindrops in stream was overcome by howling and the thin trunks of the few shivering trees of the riverbed were swept into bowed arches. It struck, so suddenly that it tore the handful of sticks from Milarepa’s hand and they barreled off out of sight. He had to get out of the valley.

Milarepa fought with the wind as he made for the shelter of the rocks by the northern canyon wall. The wind whipped his robes against his bone thin legs as he ran. As lightning struck the clump of trees behind him they exploded into splinters. He scrabbled up the path leading down from the mountain. His cave was not far. The rain poured harder, turning the path into a sluice of muck. He slipped again and again, holding tight to boulder and scrub to keep from sliding. His panting tore at his throat. He grew dizzy with each step and his vision became riddled with black spots. He came upon the wide ledge where his cave lay. The spots grew and grew. He flung open the rude wooden door and collapsed onto the stone floor, panting. His vision failed completely. His hunger had given way to nausea. He could not lift his arms.

He wondered if he would die. Twelve years of practice came to an end on the floor of his cave too weak to save himself. He thought of his guru. Oh, Marpa, how I need you now. And he remembered no more.

…

The rain broke around noon.

“Do you think they’ll call the meet?” the Runner asked the starting official.

“No, no. Got to keep going. Got to run. Got to run.” He grinned wide beneath the brim of his raincoat. “Got to run. No question about it.”

“Good, good.” The Runner said after too long a pause. “That’s good.” The knot in his stomach tightened. He hoped there was a hurricane.

At 3:30 the rain had ceased. The temperature had risen. The clouds remained overcast. The Runner was stepping onto the line of the 400 hurdles. His heart was thumping a mile a minute. Easy does it. He thought. Easy does it. Teammates lined the fence.

“Let’s get that 53” came the voice of his coach over the din. The Runner nodded. 53 seconds. He hopped from foot to foot. 53. 53. 53.

“Runners to your marks” came the starter’s voice over the microphone. 53.

“Set.” 53.

Bang. The man in the lane to his right went out hard. The Runner went with him. He sailed over the first four with ease. Nice and controlled. Nice and practiced. 53. He kept the man just in front of him. A good rabbit to chase. Over the fifth fatigue began to set in. Expected. He stuck to the rabbit like glue. 53. They leaned into the curve. Over the sixth. Still smooth. His lungs were heaving now. It would be time to make a push soon. Over the seventh. Now. It had to be now. He came out of the final bend throwing his arms back and forth like a locomotive engine. The rabbit chugged along just as steadily.

As the curve gave way to the final straight away he observed the rows of hurdles straighten themselves out from the stagger, just like ballet dancers in their final movement. Panic knocked in his chest. They came to hurdle eight. The Runner slammed his knee into the crossbar. Fuck! The Rabbit pulled away. He regained his balance and chased after him. The collision had thrown off his steps. No, no no! he thought as he slowed down to meet hurdle nine. Speed up! He came over the ninth row with all the grace of a sack of flour. The field surged ahead of him. It was hopeless now. Crawling over the tenth he crossed the finish line in dismay.

He panted for a while with his hands on his knees before walking to lay down in the grass on the infield, where he watched his rabbit celebrate with his teammates from his peripheral vision. He looked to the scoreboard at the head of the field. Maybe he thought. The digital orange flashed names and times. Jesus. He collected himself, threw his spikes over his shoulder, and walked back to the stands.

…

A day passed.

It was by the grace of some god that Milarepa awoke shivering in a puddle by the entrance of his cave. The still open door was buffeted on its hinges by the wind, making loud clattering thwacks against the outside wall. The rain continued to descend outside. He weakly rolled over, sat up, and leaned up against the wall of the narrow passage. His head swam, and his stomach groaned beneath his yawning ribcage. He blindly felt with a shaking hand for a sack of seeds on a low shelf beside coils of rope. Finding them, he shoveled them by the handful into his mouth. The storm had taken him by surprise.

When he finished the seeds in the bag he let his head rest against the wall of the cave, breathing heavily. He waited for his nausea to subside. His vision was starting to return, fuzzy. He whispered a soft prayer to the Buddha, thanking him for his life.

In his state of delirium he thought he heard voices coming from within the main cavern, echoing off the walls. He strained his ears against the rain. There was bustling and crashing on the floor of the cave, and, yes, someone was talking. He listened.

There was a deep gurgling sort of voice, like a tar pit speaking. It said, “…in fact, Fair Ones, there is a yogi who lives in this very cave who is revered as a great sage by all the people of the Dro Wo Valley.” It was talking about him!

“Oh! Very nice, very nice!” came a nasty screeching voice.

“They say he can perform magic. They pray to all the gods that one day he will return to teach them the Dharma, because, you know, the master at Dro Wo monastery is getting very old.” That master is Marpa! thought Milarepa. So, he is still alive. Milarepa often calculated Marpa’s age. He was already an old man when he had sent Milarepa to the mountains. He longed to see him. Marpa would have been able to help him.

“But, he cannot come down from the mountains.”

“Can’t do it, Chief! Can’t do it!”

“He cannot return until he achieves the enlightenment of the Buddha and becomes a master himself.” Who were these men, who knew so much about him? They must be from the Dro Wo valley. But what were they doing in his cave? And what was that scratching sound, rumbling sound? “He has been here for twelve years, Fair Ones! Twelve years. And not a single day of progress has he made in his great task. What use is a guru if he is not enlightened?”

“Not good enough! Not good enough!” Milarepa seethed. Surely by now, he had guessed people in the valley would be talking, wondering if he would ever return. But to come here to his cave and mock him! He stared into the dark of the cavern, seeing no one. They must be one of the gangs of robbers who had stumbled on his cave in the storm and, having guessed its owner, were having a laugh before making off with what little he had.

“To what people has he given guidance? Who has he led to path of the Buddha?” The remark stung Milarepa to the core.

Then came a sardonic deep throated listener with a parody of sobs. “Not a single one, Chief. Not a single one.” These fools! These criminals! Milarepa struggled to his feet and grabbed a walking stick leaning against the wall. He leaned heavily on the staff as he made his way in the direction of the voices.

“This yogi pretender has abandoned the poor people of the Dro Wo Valley. He will never return because he will never be enlightened. He is not wise enough. He did not study hard enough. And that is why,” came the leader, “to fill his absence, we must preach our dharma, Fair Ones.”

A round of applause.

The robbers erupted in laughter.

“Where are you?” He shouted, even angrier. He swiped his stick to and fro across the cave, hitting nothing. He almost fell in his weakened state, and steadied himself on the wall.

Fingers snapped from nowhere, and suddenly the wall torches, extinguished since yesterday, sprung to life. What Milarepa saw in the new illumination were not robbers at all.

…

The Runner felt, as he did each week, like something of a wash out. It wasn’t that he was slow. No! It was only that he couldn’t seem to run any faster no matter how he tried. Once again he had finished in 54.26 seconds‒ the same time as the last week, and the week before, and before that, and before that. He had run the same time for two years. 54.45, 54.09, 54.72. In fact, he had run the same exact race for two years. He would run a beautiful 300 meters, it would seem as though he was going to break from his pattern of frustrations and burst forth into the sunlight, only to implode in the home stretch. There was something about the seeing the finish line which panicked him and sent him careening into crossbars. He was stuck. Plateaued. And he was beginning to lose hope.

He walked back to the stands the long way to avoid the post-race ritual dialogue with his coach, where he was told he had done a good job, was asked how he thought, how he had felt during, and most famously “what happened in the last stretch?” It was then the Runner’s turn in this little dance to give some vague and evasive response, such as “I don’t know what happened there, coach, I just got tense towards coming around the last turn. Couldn’t get over them.” He would claim anything, from injury to the weather to poor sleep the week of due to coursework, to avoid discussing how each time he entered the final hundred meters a bolt of panic shot through his chest and his muscles contracted like cold rubber bands. He just had to shake it off. He would snap out of it.

As he approached the benches he avoided the eyes of his teammates as they bestowed the customary and unified congratulations on a race well run. They knew and he knew it had been ugly. He muttered thanks enough before throwing on his rain jacket. He sat himself down on one of the cold metal benches beneath the team’s canopy intent on brooding.

“You could have won that race,” came a voice from behind.

The Runner looked round to see who it was. “Oh, hey Farsfield.” He hoped he would go away.

Farsfield was older. He had sandy brown hair and freckles dispersed around his nose and cheeks. His big ears extended out beyond his square crew cut. He was prodigiously slim and tall and his uniform was always too big for him. During races he could be seen pulling his jersey back over shoulders. It was a little comical. But he was certainly fast.

…

Before Milarepa were five of the ugliest demons in all of Tibet, all laughing their awful laughs amidst the crashing and rustling.

“He’s here! Oh, he’s here!” It was the screeching voice. “That’s the one you were just talking about, Chief! Let’s eat him, Chief let’s eat him!” A bird beaked beast with bulging bloodshot eyes was rolling about on the floor laughing. His face had been wrinkled by a lifetime of scowling and frowning and teeth baring. A pair of black feathered wings and his skin was utterly covered in tattoos depicting scenes of battle. He was a living tapestry of horror and bloodshed. Cities crumbled upon his chest and arms. Soldiers fell to the sword. Armies burned and stole and left the smolder behind them.

“No, no.” Came the heavy voice next to him. “We’ve got to convert him. That’s the Chief’s orders.” Somehow his chuckling maintained an element of moroseness. He was a hulk of a body, with grey skin like rock and fangs the shape of scimitars protruding from beneath great fat lips. Even as he laughed his face was etched with the marks of sadness. As though he were a living stone who could not escape the birth of a carving he did not ask for.

A crash pulled Milarepa’s astonished attention to the floor on the opposite side of the cave. Two more demons were wrestling over a canvas sack of bhat. The winner at the moment was an impossibly fat princely figure, whose ears drooped with golden hoops and whose arms were covered in silver bangles. He was crushing a skeleton, whose sun bleached fingers still clung to the sack. “It’s mine you great oaf!” the skeleton rasped, pulling the sack close to his chest.

“I saw it first you little freak!” roared the prince on top. He was sweating profusely. The skeleton wriggled out from beneath him and climbed onto his back. He was choking him now with his necklaces. The prince spluttered, and dropped the sack. He reached overhead and threw the skeleton, whose bones clattered on the floor. They both dove for the sack.

“Here, Fair Ones, is the very man himself. Our gracious host!” The laughter redoubled.

“Oh that’s a good one, Chief. That’s good!” screeched the bird.

Milarepa now looked upon the last demon. He was standing on Milarepa’s bed, using it as his stage for speaking. He was taller than the others, and towered over them from the bed. Two great buffalo horns protruded from his head. His skin was deathly white, which enunciated his black sunken eyes, which were lidless and unblinking. But, his most striking feature was his impossibly wide mouth. It gaped in a sinister smile filled with needlepoint teeth, and was bordered by red lips the color of blood. His looks and demeanor struck Milarepa with a terror which he worked hard to suppress.

“Welcome home, Milarepa” said the Chief.

Recovered from his initial shock Milarepa wondered if perhaps he was hallucinating in his famished state, but the wreckage of his cave assured him he was not. The sanctuary had been destroyed if not ransacked. His books and scrolls lay torn and scattered. His figurines of the gods and goddesses had been melted down in his cauldron. Ash from the fireplace had been kicked across the cave floor. He mustered his strength, took a deep breath, and left the wall.

“Demons,” he shouted. “You must leave this place at once! This is holy ground that you defile. Lest the Wrathful Buddha descend upon you in his unspeakable anger, I banish you immediately! You will never again set foot in this sanctuary!”

Even the Skeleton and the Prince stopped wrestling for a moment to share in the renewed wave of roaring laughter. Milarepa’s anger fizzled into shock and despair. The demons made no sign of leaving.

…

Farsfield sat down next to the Runner and stared at him intently while adjusting his uniform. “You could have won that race,” he repeated.

“I know” said the Runner. Perhaps if he gave him short answers he would give up and leave.

“You’re faster than them” said Farsfield.

“I know that, too” replied the Runner curtly. Farsfield had a bad habit of not realizing, or not caring, when he wasn’t wanted

“Then what happened?”

More than a little annoyed, the Runner offered the usual. “Yeah,” he said with a sigh, “I don’t know what happened. I just locked up in the last 100.” He looked at Farsfield, trying to read his expression. It was blank. “Seems to happen a lot. Just unlucky, I guess.” The Runner tried to keep a pleasant and inquisitive smile on his face by exhaling through his nose.

“Bullshit” said Farsfield. “Accidents don’t happen every week.” The Runner dropped his smile.

“Look, I don’t know what to tell you, Farsfield. I got to the end and I started hitting hurdles. I don’t know why.”

Farsfield looked at him hard. “I don’t believe you.”

“Why don’t you go and watch the 5k, or something?”

Farsfield made no sign of getting up.

…

“What do you want?” asked Milarepa.

The Chief’s laughter subsided, and the others quieted themselves in suit. “We have come to convert you Milareppa. We are here to show you the virtuous path of the Demons.”

The two on the floor cheered and clapped. “Brilliant! Brilliant!”

Milarepa was indignant. “Do not try and tempt me demon. It bodes ill for you. I am a protector of the Dharma of Buddha Shakyamuni. I am a servant of the gods and an enemy to the Asuras across the sea. I am the student of Marpa the Translator of the Dro Wo monastery where I studied the Dharma for 10 years in yogic practice. I protect this sanctuary. You will leave here immediately and return to your holes in the mountains where you can do no harm.”

The all laughed again.

“You cannot cast out that which is yourself, Milarepa” said the Chief. Milarepa was puzzled. The Chief’s words didn’t make sense. His confusion must have shown because the Chief continued: “Think, old man. Have you remembered none of what Marpa taught you? The mind is inherently empty and still. It is like a signless ocean, smooth like glass.” The Chief began to gesture with his hands as if preaching atop Milarepa’s bed. “It is pure and perfect in its calm. It transcends all emotion; sorrow, joy, anger, lust, greed, envy.”

“But the mind, as soon as it engages in thought, is corrupted, because no thought is a pure expression. Thoughts are definitions. They are labels. They allude to characteristics, relationships, judgements. They distinguish one thing from another. Any thing is attached to a thought, and only exists as that thing because of how it is perceived. The most beautiful copper statue of the Buddha is only beautiful because it is perceived as such. There is no objective beauty. Only a definition conceived. Definitions such as these lead to dualities. Opposites. Because there is beauty there is also ugliness. Man sees the depths of sorrow because he knows the crests of joy. He wants because he knows what it is to have and not have. He is easily angered because he knows pride and shame.”

“Thoughts are like waves on the pure ocean of the mind, making the appearance of difference. But thoughts arise within the mind. They are of the mind just as waves are of the ocean. Therefore, the turbulence which man perceives around him is nothing but thought, which is in turn only his own mind creating distinction. He is tossed about on the swells of his mind’s ocean not realizing that he has created the storm himself. In fact our very own Marpa once said that‒

“All beings and all phenomena are of one’s own mind. The mind itself is a transparency of Voidness,” Milarepa interrupted. He remembered the lesson. “How does a demon know such things?”

“I know because you know, Milarepa. I am you. You created me. You created all of us” he gestured round at the wide eyed snarling audience.

“That is not true!” shouted Milarepa “I rid myself of you long ago.”

The Chief flashed his ghastly smile once more. “Oh, don’t be so surprised, Milarepa, it doesn’t become you. We never left you. Not for a moment. Oh, you ignore us in the worst of ways. You sit, day in and day out, wasting away in that saintly skull of yours, hushing us, bullying us, pretending we don’t exist. But sooner or later we were bound to bubble up. It was only pretend, you know. You wanted us gone so badly that you let yourself believe it when we seemed silent. But we were always there, dormant, just under the skin.”

…

Farsfield sighed. The Runner debated whether or not he should get up himself and leave Farsfield, but the gangly buzzcut would probably just follow him.

Finally Farsfield spoke. “That race had nothing to do with anything physical,” said Farsfield.

“What?” What was Farsfield getting at?

“There was nothing physical about it. You can run just fine.”

Alright, so Farsfield wanted to play therapist. The Runner clapped his hands to his knees. “Oh? What a relief! Then, what is it Farsfield? What’s my issue? Do you have a diagnosis?”

Farsfield swallowed what must have been some angry words, and settled on an eye of supreme annoyance before he spoke. “I watched you. I watched you run 300 meters of a beautiful race. I watched you look smooth‒ you were the only one not clapping the cross bars through the three. You lead with your right the whole time, right up until the last bend, which means your steps were on. Then, I watched you fall apart for no reason. You were stronger than them. You were quicker than them. You had better form. And I didn’t see you trip over your shoelaces. Something’s going on up here.” Farsfield tapped his skull.

“Look, I tensed up. Maybe I get tense when I’m tired. That’s what happens to people when they’re tired.”

“Yeah? Maybe. But we all watched you run 54 seconds last week in practice. It was a time trial. And you just sailed over those things. And you didn’t spontaneously combust three hundred meters in, either. No, you were smooth, like a gazelle. Just bounding. But you get in a race, where it counts, and you just lose it. So, no. I don’t think it’s because you just get tense when you’re tired. You were plenty tired last Wednesday and you finished just fine. Whatever this is, you’re making it happen.”

The Runner seethed. First Farsfield wouldn’t leave. Then, he insisted on trying to rip him apart. What was Farsfield’s issue, and why couldn’t he be content with polite conversation about the shitty weather, or something? But, beneath his seething was a kernel of anxiety. Farsfield was asking the questions he had gone to great lengths to avoid for the last two years.

Farsfield had made it clear that he wasn’t going to be dissuaded. So, with no foreseeable way out, the Runner gave as vague an answer as he could. “Alright, there’s some stuff going on, when I’m out there,” he said, nodding towards the track. “I’m thinking too much.” He had to drag the confession out of his oesophagus.

Farsfield’s face showed a genuine concern. “What is it?”

This stubborn little prick. “I really, really, don’t want to talk about this with you, Farsfield.”

Farsfield stared at him as if he were studying a specimen under a microscope. His eyes locked with his own and he intensified his gaze, searching his irises. “You’re not afraid of the pain,” he concluded. “You’re too used to it by now, it doesn’t bother you like it used to.”

“Farsfield, what are you doing?” The Runner shook his head in disbelief. He was trying to psychoanalyze him.

“It’s not burnout.” Farsfield had his hand on his chin like some goddamned philosopher. “You come to practice early every day. If it were burnout you’d be late.”

“You’re being ridiculous.”

“It’s not an injury. If you’d been running through anything serious for two years even you would have to say something. And it’s not‒

The Runner interrupted him. “Look, just because you dragged it out of me doesn’t mean you get to know all about it. You’re not Freud, and you’re not anybody’s fucking saviour. I’ve got some mental stuff kicking around when I race. Fine. You can satisfy yourself with knowing that you brow beat me until I said it. But, I will handle it. And I don’t need you, or Coach, or anybody else, playing doctor. I will figure it out, and I’ll run just fine. Now, why don’t you go bother somebody else?”

Farsfield looked as if he would blow smoke from his nostrils any second. “I don’t know why I thought I’d waste my time trying to talk to you. You’ve got it all figured out, right? You don’t need anybody’s help. Well, I’m going to give you my own, personal, theory of why you’ve run the same clusterfuck of a race every weekend for two years. You’re afraid.”

The Runner opened his mouth to protest. Farsfield cut him off. “You panic. Every time you come around that last bend, and you see the finish line, you fall to pieces. You panic and you get tense, and your muscles lock up like tetanus. And then you start falling all over hurdles.”

“I told you I will handle it” the Runner said, raising his voice. Teammates nearby started to titter uncomfortably and avoided looking under the canopy. “Look, I’ve made it pretty clear I don’t want to talk to you, so leave me alone.”

“Well,” said Farsfield. “Then I wish the best of luck.” And with that he rose, and made his way down the stairway to the track making metallic thuds with each step.

The Runner opened his mouth and faltered. He hadn’t meant to get so angry. He tried again. “I’m sorry Farsfield,” he called, “I didn’t mean it.” But Farsfield made no sign that he heard.

…

Milarepa was both awed and ashamed as he looked upon the demons and the destruction of his sanctuary. The room was silent now, save for the thudding and crashing of the two demons who had not ceased their wrestling since his entry. The demons stared at him. The Chief with his impossibly wide grin. What he saw, he knew, was a reflection of himself. In its states of chaos and disrepair. The broken shards of pottery. The beasts which blinked at him. The two who throttled each other in the corner. If Marpa could have seen he would have roundly beaten him. There was no greater evidence of his inability than what he saw before him. Milarepa felt as though he might be sick.

He breathed in.

But, an idea began to declare itself. His face brightened. If these demons were truly his own making, then he himself should also have the power to defeat them. But, as the Chief had said, he could not banish what was himself, so perhaps‒ oh how foolish I am to try to dispel these manifestations physically!

“Ghosts and demons, enemies of the Dharma,” Milarepa exclaimed. “I welcome you today! It is my pleasure to receive you! I pray you, stay; do not hasten to leave; we will discourse and play together. Although you would be gone, stay the night; before you came, you vowed to afflict me. Shame and disgrace would follow if you returned with this vow unfulfilled. Drink the nectar of kindness and compassion, then return to your abodes. ”

This time the demons did not laugh. In fact, they shifted uneasily. And suddenly Milareppa knew their names. He recognized them. He lay claim to them. They were none other than himself, and so they must be allowed to stay. “Anger” he said to the winged demon covered in tattoos “please won’t you stay in my house? I would cherish your most holy company.” Anger gawked before dissipating into thin air like so much smoke. “Sorrow,” he turned to the granite looking hulk, who put his hands over his ears. “I will prepare the most lovely bed for you if you would only stay the night.” And Sorrow too disappeared. “Greed” he spoke to the gaudy man, who looked at Milareppa even as he struggled for the rice. “Please, be my guest tonight and we will share the most wonderful stories.” A look of pure horror came into Greed’s eyes before he too dissipated. “Envy,” he said to the skeleton, who pounced on the bhat and shoveled handfuls into his mouth. The grains spilled from from his skull down his rib cage and scattered on the floor. “Envy, stay with me tonight, and I will make you the most delicious bowl of bhat you will ever eat.” And Envy, too gave a look of utter surprise, before he crumbled into dust and disappeared. “Where are you going?” called Milarepa, “I am no longer angry at you. I was only angry because I was afraid. But now that I know you are manifestations of my mind, I am so pleased to see you. We are the same. Please come back!” But they were gone. Milarepa rejoiced.

“If it’s one thing demons can’t stand it’s compassion,” came the Chief with a sigh.

Milarepa turned now to face this last demon, but this one’s name he still could not say. A cold chill crept along his skin. “Who are you?”

The Chief hopped down from Milarepa’s bed with a thump and stalked towards him, his cheeks still pulled into his ghastly grin. “I’m often hard to put my finger on. “But I am just behind almost everything you do, Milarepa. Every sermon you have ever preached. Every hour you spent in contemplation. Every prayer, and every offering.” The demon drew closer. “You’ve carried me your whole life, Milarepa.” He drew back. The tattered room was silent. Milarepa studied the Chief’s face hard.

“Fear.” The name fell from Milarepa’s tongue laced with the venom of his disdain.

“Yes.” The demon hissed.

“Then, Fear, I welcome you with an open heart. Would you kindly keep me company in my cave?” Against Milarepa’s great hope, Fear did not disappear.

“I’m afraid that’s not enough, Milarepa. Anger, Sorrow, Greed, Envy‒ you can free yourself of these because you can easily accept them. But I will always be with you.

“I will conquer you like the others.”

Fear laughed “You’re only lying to yourself, Milarepa! If you believed that I would already be gone,” he snarled.

“I tell no lies!”

“No,” said Fear, “I tell no lies.” He gestured towards himself with crooked fingers. “For 12 years you have sat in this cave, meditating, wasting away. You bear up, old man, against the elements. The night time cold that chills your bones. The sun that bakes these rocks. Up and down the mountain for firewood, chanting, chanting, chanting. Dutifully you inhabit the emaciated life of the ascetic. All of it,” he spat, “without making an inch of progress. No great enlightenment! Nothing but what you walked into the hills with!”

“And why? Man is afraid because he knows success and failure, and you, Milarepa, cannot stand to fail. You are afraid. Deeply, deeply afraid that you will die without ever achieving your quest. You will die disappointing Marpa, and leaving the rest without a leader. You wonder, late at night when your guard is down, if you’re even half the sage they claim you to be, knowing that you can never show your face in your village until you achieve what you set out to do. You cannot bear to look your master in the face, who you adore to your ruin, until you succeed in the trials he has given you. You are petrified by the prospect that you are not the man you hoped you were, and so I am enthroned.

The irony is that the very thing which motivates you to succeed is the same which obstructs you at every turn. You will never be enlightened so long as you live in terror. You will live with the grip of the world around your throat and choke on your own misery, Milarepa. Failure is an ever present possibility, hanging over the heads of every sentient being. I do not vanish because you can always fail.”

Milarepa stood speechless. He felt as though he were a window pane shattered by the powerful gaze of another. He felt like the shreds of the canon which swirled around the floor in the wind let in by the still open door. He lowered his eyes, crushed once again. It was true. All of it. He could not deny it. The thought of returning home having failed was more than he could bear. “All that you have said is correct.”

…

The Runner dropped his duffel bag on the floor of his room, and rummaged for his water bottle. He couldn’t stop Farsfield’s words from bouncing around his skull. Even when he wasn’t around he wouldn’t leave him alone. By now his anger had been replaced with a leaden feeling in the pit of his stomach. Farsfield had cut through him like wire through clay.

Finding the bottle, he strode to the bathroom sink to fill it up with water. The trouble was not getting tense in the last 100 meters. That was only a symptom. True, a symptom with an obvious effect, but not the root. The truth was just as Farsfield had guessed, though he’d never tell him that. Every time he reached the final hundred meters he panicked, without fail.

He caught a glimpse of himself in the mirror, and looked up. He looked haggard. Worn. What are you afraid of? He asked of his reflection. It stared back at him. He blew air out of his nostrils, waiting. Failure came the answer. He nodded, and continued to lock eyes with the reflection. Why? he asked. Because of what failing would mean answered the reflection.

What would it mean?

It would mean you weren’t good enough. You didn’t make the cut. It would mean you didn’t work hard enough. That you were slow. It would mean all your teammates and coaches watching you, wondering why you never quite lived up to their expectations. It would mean that you weren’t the person you thought you were, and that would rip you apart. You can’t fail. You’re not allowed to fail.

But everyone fails. The reflection stared back blankly. If everyone fails, he asked, why should I be any different?

Maybe you’re not. The Runner frowned.

…

“Look at me and say it,” Fear whispered. Milarepa could not bring himself to meet the demon’s eyes. “Look at me, Milarepa. Look into my eyes and say it.” Milarepa did not move. Fear took Milarepa’s chin in his icy grip and jerked his head up to face him. “Sing me my psalms.”

Milarepa stared into Fear’s empty, black, eyes. “All that you have said is true. I have lived in terror of defeat such that I have utterly failed. I am destitute. I am broken. And,” he faltered, “I am giving up.” There was a certain relief in voicing what he had long dreaded to say.

Fear looked wary. “Tell me of your terror.”

It was over now. He had tried, and he could not succeed. The greatest disaster of his life had been realized and he felt light as air. “Fear,” Milarepa stared at the demon with intense earnestness, “I have failed. And since I have failed, and will never have a mind free from you, it is only right that you be my guest. But, since I have not enough to feed you, you must eat me.”

Fear tightened his grip on Milarepa’s jaw. “Cease your ravings, old man.”

“Fear, you must eat me! Please! You are my guest and I have not enough to feed you. You must eat me!

Fear stepped back, “Get away from me,” he snarled.

Milarepa let out a fierce yell and ran at the demon, who stumbled backwards and braced himself against the wall behind. Milarepa placed his hands around Fear’s jaw, and pried it open. “I have failed because of you, Fear. Now I place my head in the mouth of failure! I accept that I have failed! I rejoice that I have failed! I praise the Tathagata in his kindness for allowing me to experience such an utter and total defeat because I am no longer beholden to you!” And he thrust his head inside of Fear’s mouth.

Fear shrieked, and vanished as if he had never existed at all.

Milarepa stood panting in a cold sweat, with his head thrust forward in the space where Fear’s mouth had once been. He took a deep breath and smiled. He felt as if he had lived inside a leaden shell his whole life and had only just burst through the cracks and emerged.

He set to sweeping up the mess the demons had left in his cave. When he finished, he knelt down in the middle of the floor, and fell into a deep calm.

…

The Runner took deep breaths in through his nose in lane three as he hopped from foot to foot.

“Runners, to your marks” came the static voice of the official. He looked out at his teammates lining the fence. Each of them has hit their walls before, he told himself. He picked out Farsfield’s face, before setting down into the blocks. I am no different. Did he not eat, sleep, and breathe like the rest of them? Was he somehow above harrows and pitfalls of humanity? He would fail. He would fail again, and again, and again. This is just the way it was. And if he fought it, denied it, renounced it. Well, he would he would stay stuck, and scared, and unhappy.

“Set.” The Runner brought his hips to the sky. So what was failing? He had failed, already. For two years. And the only punishment was his own agonizing. The world still turned, after all. He was responsible for his own misery. Let it go, he thought. And his muscles relaxed.

Bang.

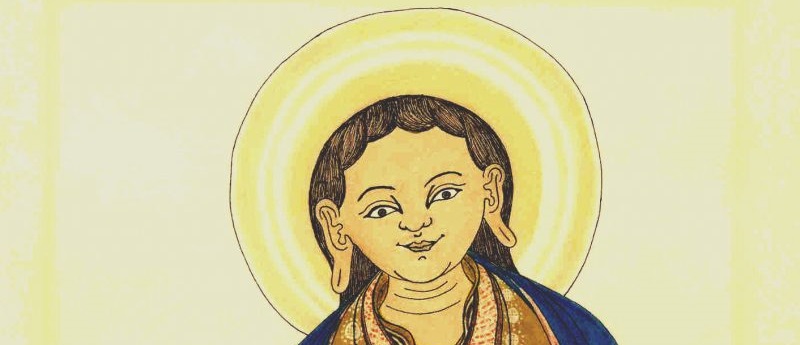

milarepa by omnos is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Return to the introduction to Athlos: A Journey through Running

Or Check out the complete list of Athlos posts