Bridget Almas

Tufts University

For the last few years we have been laboring to bring the Perseus Digital Library into the next generation of digital environments, freeing the data it offers for others to easily use, reuse, and improve upon, while continuing to offer highly curated, contextualized and optimized views of the data for the public, students and researchers. This has proven challenging in an environment where standards for open data are still evolving, the infrastructure to support it is still nascent or non-existent, and funding to improve and sustain pre-existing solutions is hard to come by. We have been tackling it bit by bit, and have been making real progress, but still have far to go.

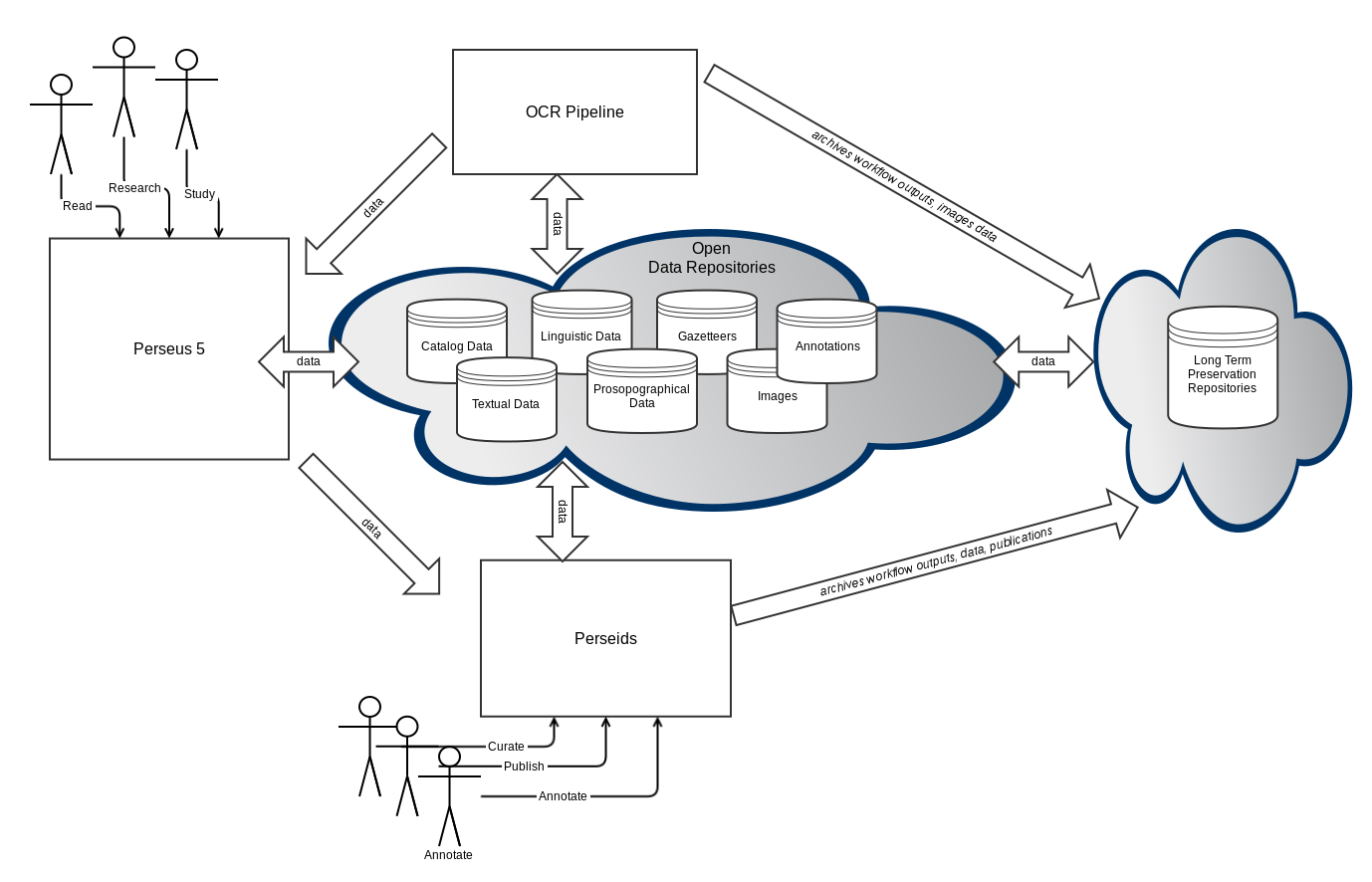

Today’s vision of the ultimate solution might look something like this:

In this vision, Perseus 5 is an up-to-date version of the current Perseus 4 interface, which still offers all the texts and related analytic and search services across highly curated collections (and readily supports this on a variety of different screen sizes and devices) but also:

- provides the ability for users to annotate and add their own contextual information

- can easily incorporate data as it comes off the OCR pipeline

- seamlessly incorporates data from other open access platforms

- in return easily makes its own data available to these platforms (both inside and outside the Perseus ecosystem)

- archives all data used by and in Perseus for the long term in institutional repositories

Making this happen requires thinking of each and every item in the Perseus Digital Library as a distinct, addressable, shareable and preservable piece of data. This includes:

- Primary source texts and their translations

- Secondary source texts and reference works

- Bibliographic metadata

- Lexical entities

- Lexical tokens

- Person entities

- Place entities

- Dates

- Images

- Artifacts

- Linguistic and Textual Analyses

- Assertions of relationships between any of the above data types

- Assertions of occurrences of any of the above data types as a fragment of or region of interest in another type

- Collections of like and disparate groupings of any of the above data types

At any given point in time, any data object in the library may be in a different stage of its digitization or curation lifecycle. We want to make what we have available as soon as it can be put online, and offer progressive improvements to the data as they become available, so the targets and scope of our publications and citations are constantly changing. We want to represent this data in a way that allows us to incorporate the millennia of accumulated data and scholarship on classical texts and languages seamlessly with the newly generated representations of today. And we at Perseus want not to be the only stewards of this data — we want our institutional repositories to help us preserve it for the next generations to come.

To do this scalably, we need an infrastructure which offers us general purpose solutions for the things that are common about each of the data types, while at the same time giving us the flexibility to treat each type of data as distinct when the need arises. For example, when dealing with a citation of a passage in a text, we need a solution that understands canonical citation schemes (Hom. Il. 1.1) and how to translate those into a string of lexical tokens from a specific version of the cited text. And when dealing with a citation of a region of interest on an image, we need a solution that can translate x and y coordinates into a box or polygon on an image itself. But we would also like the systems that manage the persistent identifiers for our data, and those that retrieve the metadata and objects associated with those identifiers, to be general enough to apply to all our objects, regardless of type. In this way, we don’t have to constantly reinvent core common functionality for each data type. And we would like the interfaces to such systems to be consistent not only within Perseus itself, but also across the ecosystem of data providers and consumers in the wider world of classical and modern texts, as well as linguistic and humanities data, so that we can share and interoperate.

The Center for Hellenic Studies’ Homer Multitext project did pioneering work in developing the CITE architecture to define machine-actionable, technology independent standards for identifying, citing and retrieving texts and text-related data objects. This has given us a solid framework within which to begin addressing some of these needs, especially when it comes to working with canonical texts and citations to them. Implementing the Canonical Text Services (CTS) URN specification component of CITE allows us to produce a semantically meaningful identifier which represents the position of a text in the hierarchy in which it is traditionally cited. This same identifier scheme can also be used to cite into the text at the passage level, within a specific version or instance of that text, or within the notional work the text represents. So, for example, while a traditional reference to Book 1 Line 1 in Homer’s Iliad as cited in literature might be “Hom Il. 1.1”, this can be represented as urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0012.tlg001:1.1, as a citation to the notional work The Iliad, or as urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0012.tlg001.perseus-grc1:1.1 in the specific ‘perseus-grc1’ edition of this work. (The CTS specification and the Perseus Catalog documentation explain these components more fully, but briefly, the other components of the URN here are a namespace, greekLit, a textgroup identifier, tlg0012, for the group of texts attributed to the author Homer, a work identifier, tlg001, for the work The Iliad and a passage identifier, 1.1).

But as a domain-specific protocol, CITE has also introduced interoperability questions, particularly when we want to leverage more general data management solutions from other domains and to be interoperable with institutional repositories. It is essential that we be able to leverage software and tools for working with our data that come both from within and outside our domain, and that are backed by communities of developers, in order to ensure the long term sustainability of those solutions. We need solutions which allow us to implement the domain-specific advantages of CITE within the context of a broader, more general framework.

The following use cases offer a closer look at a few of our highest priorities.

Persistent, domain-sensitive, identification of a text throughout its lifecycle

We need to be able to apply the aforementioned CTS URN scheme through the entire lifecycle of a text in the digital library, starting at the point at which a digital image of a manuscript exits the OCR process and is available in uncurated HOCR. At this point we should be able to put this text online, have it catalogued and assigned a CTS URN identifier so that it can be citable and reusable as data under this identifier. As the text is further curated, whether by the crowd or by individual scholars or groups of students, and undergoes revision and change on its way to a fully curated TEI XML edition, new versions are created, requiring new version level identifiers, all of which should be resolvable backwards or forwards to their ancestors or descendants. Annotations and derivative versions and analyses which are made on the early versions should be easily and automatically portable to the newer, improved versions as they come online. Citations which reference fragments of the text should be robust and automatically resolvable across versions. And while perhaps not every distinct version of a text in this lifecycle should be preserved for the long term, certain points will be flagged as requiring an archive copy – for example, at the end of a semester after a classroom of students has undertaken collaborative curation as a scholarly exercise. These archive copies which might normally be assigned handles as persistent identifiers by the institutional repository need nonetheless to retain a link to the CTS URN based identity.

Concurrent annotation and curation in a distributed architecture

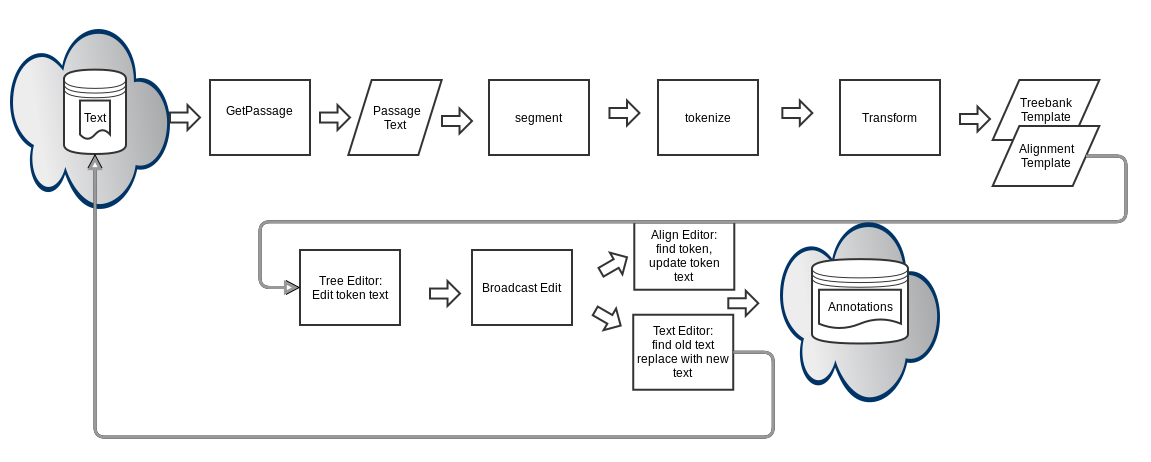

Going hand-in-hand with the need to be able to persistently identify a text and its derivative versions throughout its lifecycle is a need for annotation and curation tools which can operate both independently and together on texts as data, retaining the identity of the original data source(s), capturing and adding to the provenance chain details of any transformation of other operations the tool or its user performed on the text, and returning the improved data immediately back to its source repository for versioning and archiving. The following diagram depicts such a workflow in which a text is identified in a repository, a passage of it is extracted for annotation (in this case treebanking and translation alignment), in the process of annotation corrections to the underlying text are made, the improved text is returned to its source and the annotations are preserved separately:

Thinking about the requirements implied by these use cases, there is a core set that can be applied regardless of which type of data we are talking about. We want actors (be they people or machines) to be able to:

- assign a persistent identifier to a data object

- associate descriptive metadata with a data object

- reference a data object

- reference a fragment of a data object

- associate provenance information with a data object

- aggregate like objects

- aggregate disparate objects

- create templates of object types for reuse

- reference a specific version of an object

- reference an object before it has been published and have the reference be valid throughout the object’s lifecycle

- create data objects which reference other data objects

- reference a data object which comes from an external source

- update a data object which comes from an external source

- update a data object which we create

- assert relationships between data objects

- reference assertions of relationships between objects

- preserve data objects

- perform analyses across sets of data objects

- produce visualizations of collections of data objects and their relationships

- reference visualizations of collections of data objects and their relationships

- preserve visualizations of collections of data objects and their relationships

- notify consumers when new versions of data objects are available

- consume updated information about data objects from external sources

- provide data object metadata in a variety of standard output formats

- associate users with data objects

- search and filter data objects by various criteria, including access rights and provenance data

- identify users

- authenticate users

This is by no means an exhaustive list, but it’s enough to give us an idea of what we might need when we talk about infrastructure for managing this data, particularly when we look at them in the context of our workflows. And we are not alone in these needs. The Data Fabric Interest Group of the Research Data Alliance (RDA) recently issued a call for use cases for data management across a variety of different research domains in the sciences and humanities. Analysis of these use cases resulted in a position paper identifying core components of a data management infrastructure. These include:

- Persistent Identifier (PID) Systems

- Identity Systems for Actors

- Registry Systems for Trusted Repositories

- Metadata Systems and Registries

- Schema Registries

- Category/Vocabulary Registries

- Data Type Registries

- Practical Policy Registries

- Reusable Policy Modules

- Distributed Authentication Systems

- Authorization Record Registries

- Protocols for Aggregating and Harvesting Metadata

- Workflow engines and components

- Conversion/Transformation Tool registries

- Repository APIs

- Repository Systems

- Training on and Documentation of Solutions

There are some things that may be missing from this list as well, particularly around the needs for dealing with collections, referencing data fragments, and annotations on data which is undergoing curation or change, but the point is that the need is real, it transcends domains, and solutions will be developed.

If at Perseus we had access to these solutions today, we could focus on the things that are unique about our data, designing the user interfaces, visualizations, annotation, curation and analytical services that would drive new research, without worrying about building the underlying infrastructure to support the data. But in order to take advantage of the solutions as they are built, we must be part of the discussion about the requirements, push for our use cases to be considered in their design, and take part in testing, implementing and sustaining the solutions.

I see participation in RDA’s interest and working groups, presenting our use cases and helping to build the collective solutions, as a long-range tactic, but we also need to make concrete progress today with those tools and services that are available now and that might be able to become part of a broader digital infrastructure supporting the humanities. With the Perseids project we are building a platform for collaborative editing, annotation and publication from a core of existing tools, services and standards. In the process we are experimenting to see how we can use APIs and data transformations to connect the tools and produce sharable data. It is a messy process at times, but we are beginning to see real results.

Our strategy therefore is to participate at both ends of the spectrum, so that when things meet up in in the middle we will have a solution that is sustainable for the future.