To kick off 2020, several TPI members spent two weeks in Costa Rica on a tropical field ecology trip. While there, we saw a smattering of animals and plants, such as Costa Rica’s largest weevil, kinkajous sipping nectar from balsa flowers, and scarlet macaws; we harvested coffee on a farm in Santa María de Dota and learned to identify flavors associated with high quality beans; and released baby sea turtles into the ocean. All in all, an unforgettable trip.

Of course, we also got up close with diverse pollinators. This post, written collaboratively by TPI members, highlights our favorite pollinator groups that we saw.

Butterflies: Costa Rica is home to over 1,200 butterfly species of diverse colors and sizes. The blue morpho, known for its iridescent blue, has a wingspan of up to 8 inches! In contrast, skippers often have a wingspan no larger than 1 inch. Although they look very different, blue morphos and skippers are both fast fliers and difficult to catch (in net and on camera). Here, I snapped a picture of a skipper taking a drink from…a sweaty sock!

Although this may sound gross to us, sweat and mud puddles are an important source of sodium for skippers and other butterflies. Most butterflies only eat nectar, which provides plenty of sugar energy for flying, but is lacking in sodium. Among other things, sodium is important for water-regulation and mating in butterflies. I also had the opportunity to watch swallowtail caterpillars transition to adult butterflies. This caterpillar is in the “pre-pupal” stage—it’s beginning to shed its skin and spin its chrysalis. Once the caterpillar has spun its chrysalis, it is in the “pupal” stage. During this stage, the caterpillar undergoes many changes in order to become a beautiful butterfly!

Bats: Costa Rica is home to 112 of the over 1100 species of bats worldwide, giving the country one of the most diverse bat populations in the world, and making it an important site for bat conservation. Many native plants and crops in Costa Rica, including bananas, depend entirely on bats for pollination or seed dispersion. Bats spend their days sleeping in hollow trees and under palm leaves, and at night take to the sky in search of bugs, fruit, and nectar for food. Bats eat a huge number of mosquitos and can provide better pest control than birds in agricultural fields. They spread pollen when feeding on nectar and disperse seeds after eating fruits. And bats are the only mammal that can fly! Costa Rica is home to three species of vampire bats, and to several rare species like the honduran white bat. The next time you enjoy a banana, peach, or margarita (bats pollinate agave!) thank a bat!

Stingless bees: Although bumble bees (Bombus) are the dominant wild social bees in temperate areas, stingless bees (Meliponini) have full reign over the tropics. Throughout the neotropics, including Costa Rica, stingless bees are important crop pollinators and they are prized for their delicious and medicinal honey by bee keepers, who are known as meliponiculturalists.

Intriguingly, in addition to flowers, stingless bees also visit many non-floral resources for salt, including rotting fruit, muddy water, human sweat, urine, and even carrion. It is this last resource that sufficiently piqued the interest of two TPI members to study the foraging preferences of stingless bees on rotting meat. We hung up chicken baits that we had marinated in a variety of salt solutions and watched them over two days to determine if stingless bees are indeed going for salts when they visit meat or are instead looking for protein. Although most bees use pollen for protein, three species have switched over to a carrion-only diet, so this hypothesis is not unreasonable. What did we find? That six different species of stingless bees foraged on our baits and that they *do* have preferences: for un-soaked chicken and sodium but not for magnesium, potassium, or calcium. So, they likely visit meat for both salts and supplemental protein, and this was confirmed in our observations of Trigona fuscipennis workers flying off with pollen baskets full of meat!

Orchid bees: If you wander the forests of Costa Rica long enough, you’ll likely see a metallic green flash, darting between the trees in search of flowers. These are orchid bees of the genus Euglossa, which are among the most dramatically colored bees in the world, coming in iridescent colors ranging from bright red to blue and even violet.

Orchid bees encompass over 200 species (many of them less colorful) and constitute the most important and abundant pollinator group in much of the New World tropics. The bees are known to fly up to 40-km in a day, an astounding distance that helps tropical plants mate while far apart. They also include some of the longest-tongued bees in the world, like the gorgeous specimen of Euglossa asarophora pictured below. That long thin line extending beyond its body is its tongue, which is long even for an orchid bee! You can see how this might come in handy for reaching in very deep flowers for sugary nectar.

But orchid bees are perhaps most famous for their intricate relationships with orchids, and their highly unusual scent collection behaviors. In an effort to attract a mate, male orchid bees spend much of their day roaming the forest in search of specific scents, often those produced by rare orchids. When they come across a desirable smell, the bees scoop the smell into a specialized organ on their hind legs, where it is stored. Some orchids have evolved to produce no rewards other than the particular scent that their specialist orchid bee pollinator likes best! This trait comes in handy for humans, too: by putting out synthetic perfume compounds, scientists can attract the male bees in order to study them (or take pictures like the one of the green Euglossa above).

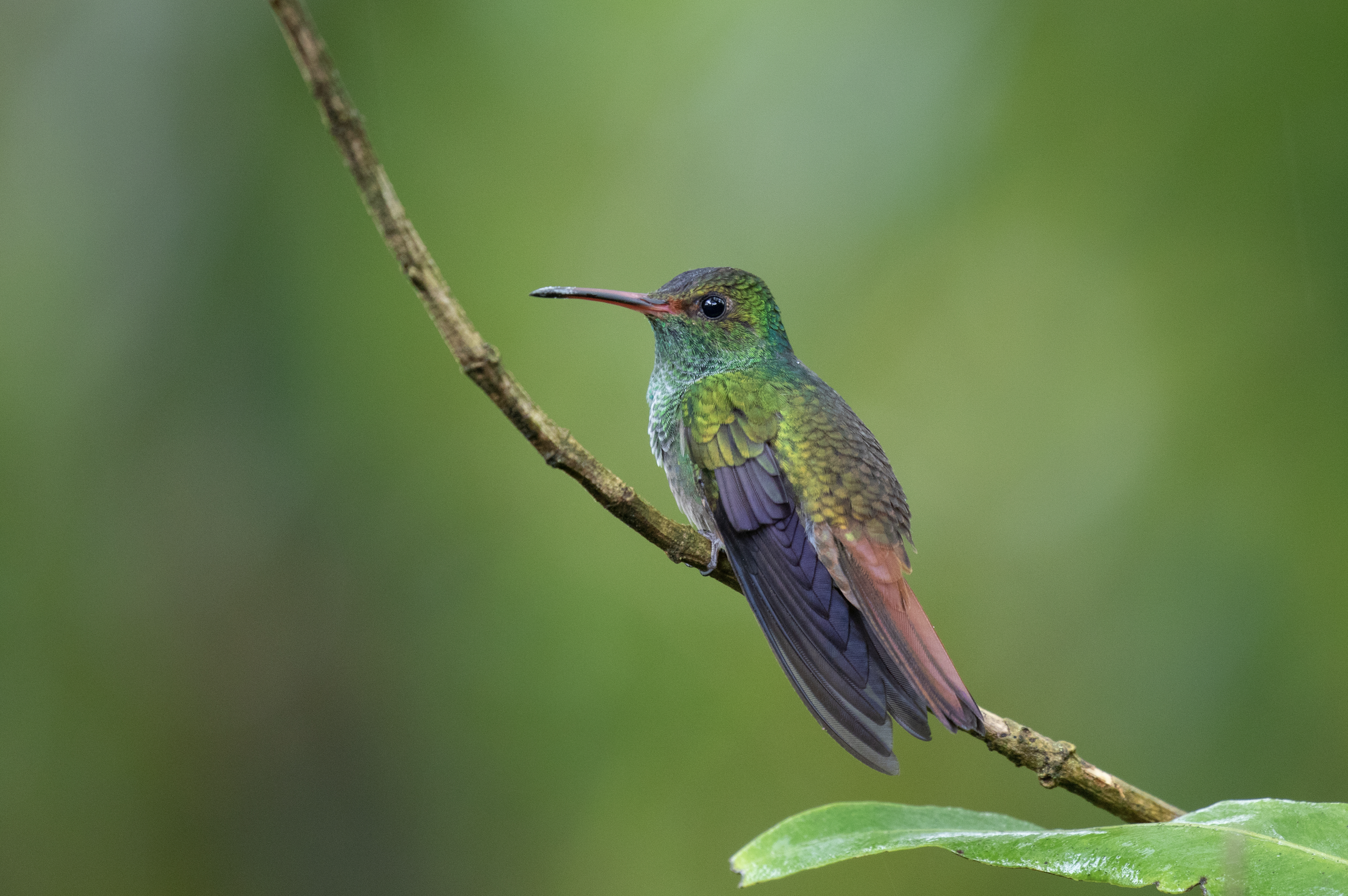

Hummingbirds: Hummingbirds’ extravagant plumage and fascinating behaviors make them some of the most well-known non-insect pollinators. While only one or two hummingbird species can be found regularly in the United States east of the Mississippi River, Costa Rica hosts an astounding 50 species, ranging from the widespread Rufous-tailed Hummingbird that can be found visiting flowers on city rooftops to highlands specialties like the aptly-named mountain-gems. Like many other groups of pollinators, hummingbirds include both generalists and specialists. Some species, known as hermits, have strongly decurved bills that are well-suited for accessing the nectar of curved Heliconia flowers. Unlike many other hummingbirds, hermits are not territorial. Rather than defend flower patches, they instead visit plants scattered around the forest floor along fixed routes, a behavior known as traplining (also seen in other pollinators, such as orchid bees!). As they forage, hermits provide a valuable service for Heliconia by carrying their pollen over long distances, often to other individuals of the same species – a difficult feat to achieve for a plant growing at low densities in the understory of a tropical forest!

Although our trip taught us a lot, it also raised a lot of questions. For example, we don’t know what most orchid bees nests look like, what sorts of microbes help stingless bees digest meat-based protein, and what will happen to mountain-gems as the tops of mountains warm. We’ll just have to wait until next time to go back to the tropics to do the science and find out!