Nothing says fall quite like pumpkins. They feature prominently in seasonal pies and Halloween decorations. Contests are held and won at county fairs by the farmers that can grow the largest pumpkins (some weighing in at more than 2000 lbs). Their appearance on the shelves of stores and farm stands marks the start of a season of aster and goldenrod, of cold nights and falling leaves, of root vegetables and mulled ciders. Amidst all this pumpkin hubbub, it is easy to take for granted our favorite orange squashes and lose sight of where they come from.

All pumpkins are a single species of squash, Cucurbita pepo, which is a scraggly vine native to the desert southwest. Over thousands of years, C. pepo was transported across North America and diversified through careful cultivation by native peoples and modern agriculture into many of the squash cultivars we love today: acorn, spaghetti, delicatta, and pumpkins. But it wouldn’t have been possible without some (tiny) help along the away.

Every pumpkin starts out in mid-summer as a female squash flower, a yellow starburst peeking through huge green paddle leaves. Squash plants are monoecious (mon-ee-shus), meaning that male and female parts occur in separate flowers on the same plant. So, one squash plant contains flowers that produce pollen (male) and others that produce ovaries (female). In order for a female flower to be fertilized and successfully produce a fruit (yes, all squash are fruit), pollen from the male flowers must be transferred to the female flowers. This is pollination.

In natural and agricultural systems, wild bees are the main transporters of squash pollen. Early in the morning, squash flowers open up and produce prodigious quantities of sugary nectar to attract pollinators. Once in the male flower, the bee is passively dusted by squash pollen which it transfers to the next female flower that it visits. And so on and so forth until afternoon when the squash flower closes, never again to reopen. Hopefully, during its single day of blooming, it received a visit from a bee!

Which bees, however? Squash bees (!), so called because they feed their offspring exclusively with squash pollen (plants in the genus Cucurbita). There are around 20 species of bees that specialize on squash, but in New England we have just one: Eucera pruinosa (formerly Peponapis pruinosa). But, this bee is not historically native to New England. Recent genetic analyses show that squash domestication and trade over thousands of years enabled the squash bee to colonize New England from the desert southwest via the Great Plains. Thus, the squash bee exists in New England solely because humans are unwavering in their love for squash. You can think about this in another way: if all of New England were to stop growing squash for a single year, squash bees would be swiftly extirpated from the area.

Since squash bees are pretty picky about the pollen they consume, their seasonal activity period is limited to peak squash flowering season in Massachusetts, generally from mid-July to early August. Males emerge first and quickly establish territories at the best place to find a female squash bee: squash flowers! Although male solitary bees are often considered only useful as mates, because of this behavior, male squash bees are uncharacteristically good pollinators; they contribute heavily to the $200 million annual industry of pumpkin production.

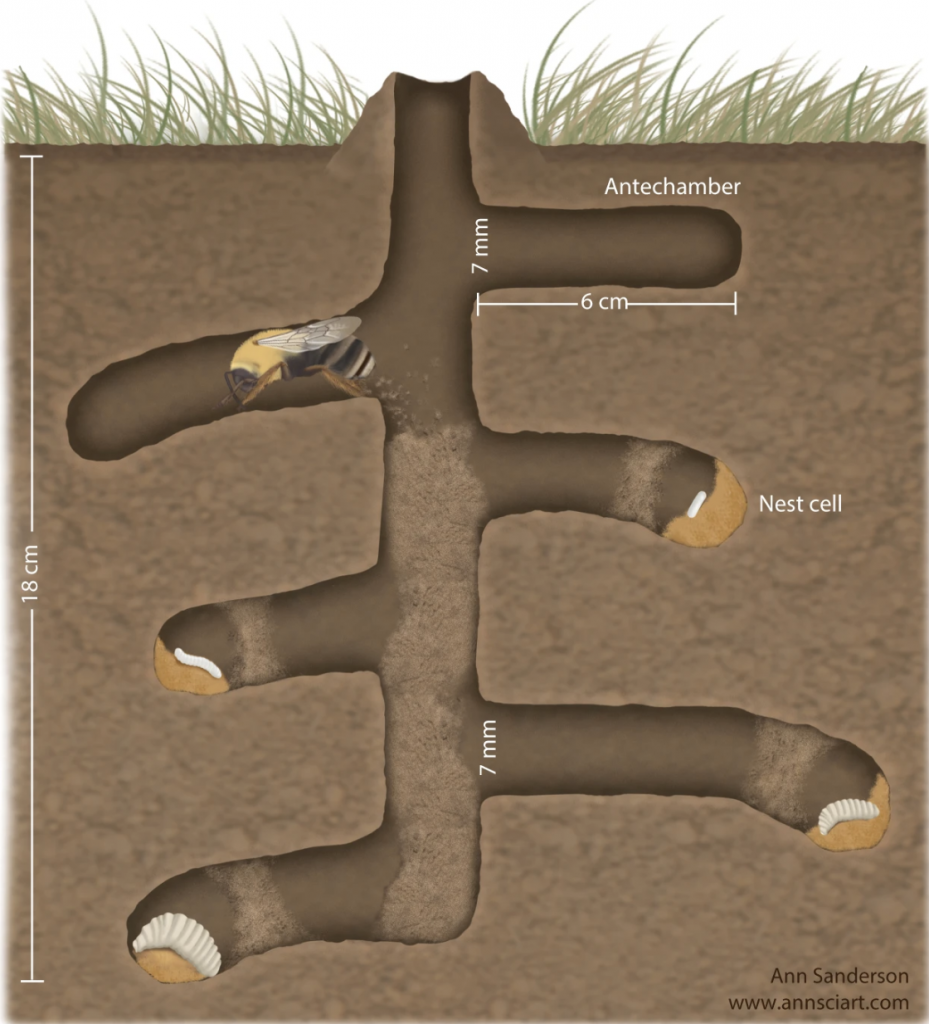

Once mated, female squash bees build their nests at the edges of squash fields in bare, packed soil. Because they are solitary, every female builds and provisions her own nest, though often nests will occur in close proximity to one another. She excavates a narrow tunnel through the soil, and every day prepares a chamber, fills it with a stiff oval of squash pollen and nectar (think play-doh consistency), and lays a crescent-shaped egg. This chamber contains everything the young squash bee needs to develop from egg to larva to adult. Squash bees will spend the winter underground and won’t emerge until the following summer when squash is flowering again.

How good are squash bees at making pumpkins? So good that many farmers refused to believe it. Historically, squash pollination was supplemented with commercial hives of honey bees and, in some cases, bumble bees. Yet, it has been shown that farm fields supplemented with managed bees do not produce bigger yields than ones receiving only wild pollination. There are two explanations for this. First, most other bees refuse to collect squash pollen for their offspring, possibly because of distasteful chemicals. Thus, managed bees are only visiting squash flowers for nectar and come into less contact with pollen. Second, squash bees are such efficient foragers and their daily schedule so synchronized with the daily schedules of squash flowers, that by the time other bees arrive, the flowers have already received sufficient visits to produce big pumpkins. Still, many farmers bring in managed bees to pollinate their pumpkins as an insurance policy.

This Halloween, if you carve a pumpkin or drink a spiced latte, thank squash bees. Our obsession with pumpkins enables these abundant pollinators to survive and grow in the most unlikely of places (even in the middle of Medford), and their unrelenting obsession with cucurbit pollen gives us more pumpkins than we know what to do with.

P.S. If you want to get a close up look at a squash bee, one afternoon, late next summer, find a closed squash flower in a garden. Chances are that a male squash bee is dozing inside, perhaps having found a mate that morning or just missed his opportunity. Look for goofy-long antennae, ochre hairs, and a boldly striped abdomen.