As you start (or finish?) your holiday shopping, here are some gift ideas to spread the love of pollinators.

For beginner and/or experienced gardeners

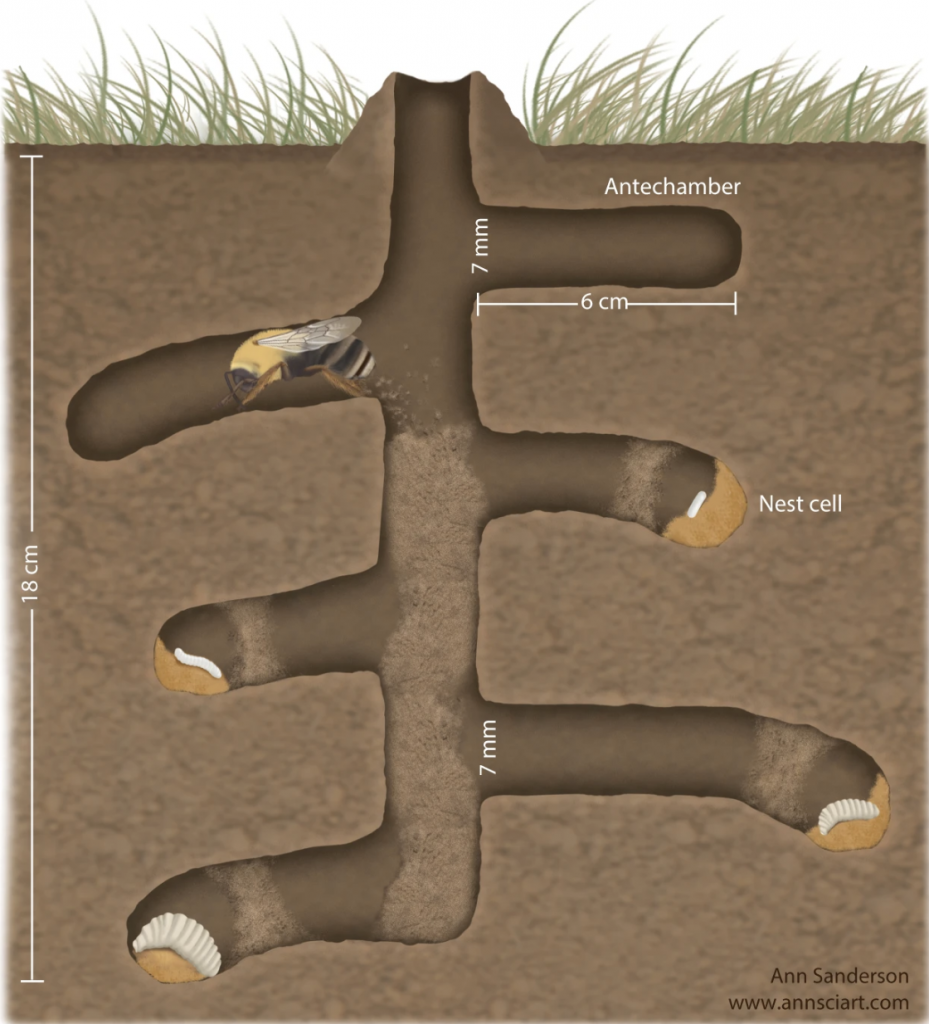

- Bee hotel/DIY kit: Bee hotels are a fun and easy way to support native bees in your own backyard or garden. While most people think about honey bees when they think “bee,” 90% of bee species nest alone in tunnels or holes. Putting out a bee hotel near your garden will provide more real estate for these bees. Here is a list of various bee hotel options.

- Pollinator introduction kit: This kit from Prairie Moon Nursery includes Pollinator Palooza seed mix (the mix we give out), a bee hotel kit, and a book on attracting native pollinators.

- Pre-planned garden: For those who would like a pollinator garden but don’t want to do the planning, Prairie Nursery (not to be confused with Prairie Moon Nursery) sells a variety of pre-planned pollinator gardens complete with plants, planting instructions, and a design map. All gardens include a variety of perennials that will keep your garden blooming (i.e. providing food for pollinators!) from spring through fall.

For readers

- Subscription to 2 Million Blossoms: The gift that will keep on giving through 2020, 2 Million Blossoms is a new quarterly magazine dedicated to transporting its readers to the world of pollinators. In the first issue, readers will get “distracted by bees” in my photo essay about bees on a Pacific Northwest prairie, like the brilliant green sweat bee, and the wildflowers they visit.

- The Bees in Your Backyard by Joseph S. Wilson and Olivia Messinger Carril: This is one of my favorite books about bees! In this book, readers learn how to identify native bees that are likely in their backyard (in North America) and what they can do to help the bees. Gorgeous photos accompany easy-to-read text.

- Honeybee Democracy by Thomas D. Seeley: My love for insect pollinators started with honey bees. Although they are not native to North America and are more of a domesticated animal than a wild pollinator, we can learn a lot about our native pollinators from studying honey bees! In this book, honey bee biologist Tom Seeley describes the amazing ways in which honey bees work together to make decisions as a group.

For foodies

- Honey: Raw honey is one of the sweetest gifts to give (pun very much intended). You can often find local beekeepers at holiday craft fairs selling their delicious honey (sometimes gorgeous beeswax candles too!). If you can’t make it to a craft fair or they’re just not your thing, there are companies that will ship raw, delicious honey right to your door! Some of my favorites are: GloryBee, Boston Honey Company, and Savannah Bee Company. If you’re local to the Boston Area, check out Follow the Honey , a brick-and-mortar where you can find (and taste!) honeys from New England and around the world. Honey varietals make great gifts—that friend from Canada will go crazy for Canadian White Gold.

- Save the Bees Pinot Noir: Proud Pour’s Pinot Noir from Oregon will pair beautifully with that holiday roast chicken. As a bonus, proceeds go towards replanting wildflowers on farms local to where the wine is purchased!

- Beeswrap: I love my beeswrap! An environmentally friendly alternative to the plastic baggie, beeswraps are fun fabrics coated in beeswax that are washable and reusable, and perfect for wrapping up that sandwich or snack. Beeswrap can also be used in place of plastic wrap to cover and store leftovers.

For fashionistas

- “Plant these” long-sleeved shirt: Support pollinator-friendly gardening as well as an artist with this adorable shirt from Etsy.

- “Protect the pollinators” short-sleeved shirt: While TPI mainly focuses on insect pollinators, this shirt spreads pollinator love by including hummingbirds and bats in addition to insects.

- Bee Amour jewelry: Made by a beekeeper in Texas, this jewelry is inspired by some of our most well-known managed pollinators, honey bees. Some of the pieces are even cast from actual honeycomb!

For the person who doesn’t need anything

- Donate to a non-profit organization in their name! Here are some of the organizations working to protect pollinators:

Happy holidays from TPI!