We can all have a positive impact by incorporating sustainable behaviors into our daily lives, but not all impacts are equal. At universities, laboratory settings have especially high resource and energy demand, making them important targets for sustainability initiatives. Duke University estimates that lab spaces can require five times the energy of other campus buildings. For this reason, Tufts began work on the Green Labs initiative, which aimed to increase the overall sustainability of these spaces through a variety of means.

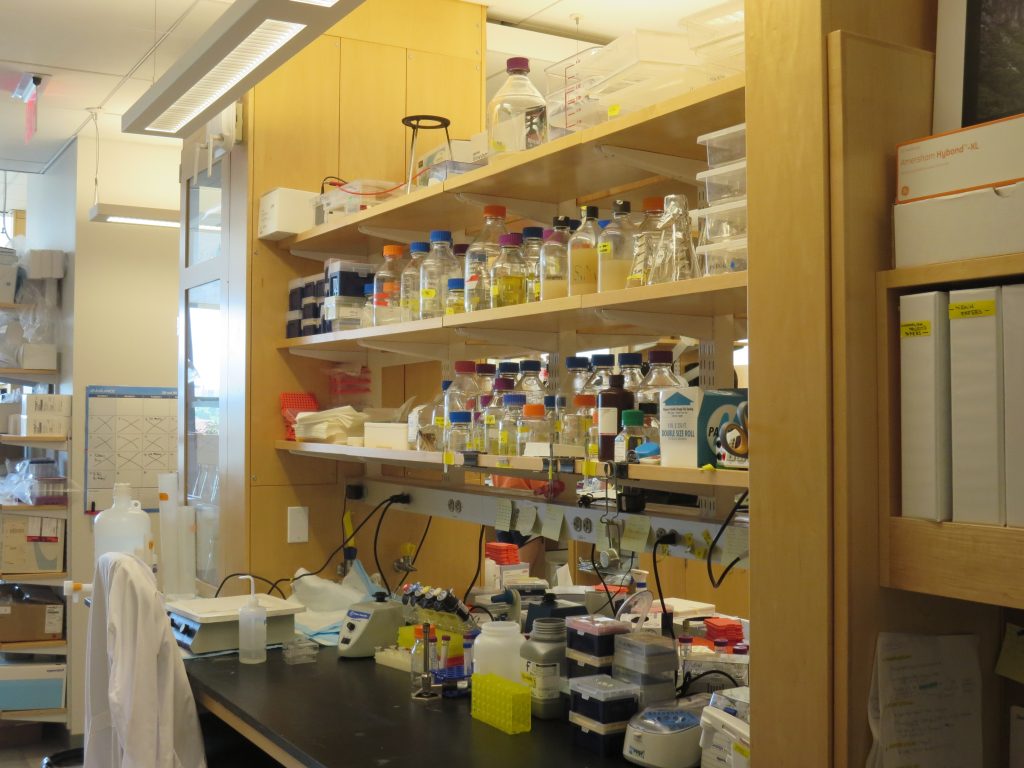

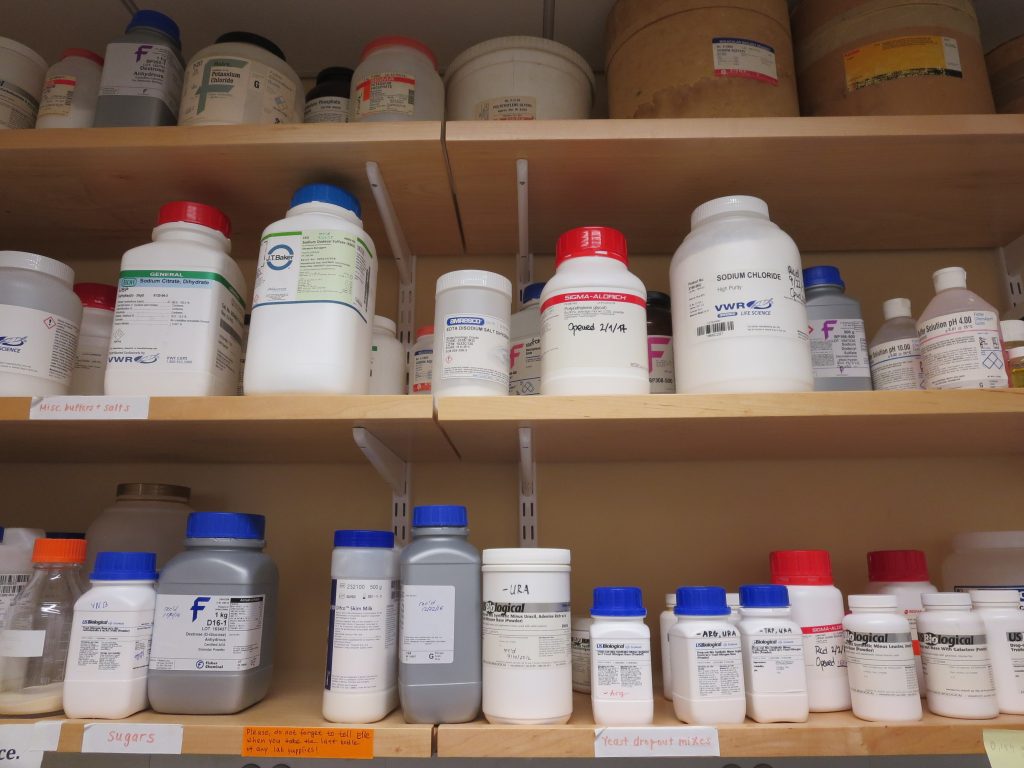

Across all three Tufts campuses, ten labs signed up to participate in the Green Labs initiative. Emily Edwards, who coordinates chemical and bioengineering labs in the SciTech building, has long been committed to increasing the sustainability of these spaces. Her department currently runs 14 labs, researching topics from solar panel development to filtration membranes to bioengineering with mammalian cells. When she first joined the department, Edwards wanted to reduce plastic waste in her labs, which use high volumes of disposable items like pipette tips, weigh boats, gloves, and vials. However, she found this to be nearly impossible because these materials are necessary for routine lab work, and are difficult to clean for reuse. In light of this, Edwards feels that energy conservation is the most practical way to reduce the environmental footprint of her labs. She worked to address this challenge through her participation in the Green Labs initiative.

Another major participant in the initiative was Sanjukta Ghosh, a lab coordinator in the biology department. Ghosh oversees nine labs at 200 Boston Ave, researching topics like molecular biology, genetics, and bioinformatics. Her building is LEED certified, and features sustainable technologies including daylight-sensitive lighting systems and open floor plans that facilitate equipment sharing. Ghosh has an academic background in green chemistry philosophy, and has applied these sustainability concepts to her work at Tufts. She also acknowledges the environmental difficulties of lab work, which inherently creates a large plastic footprint. Ghosh has recently worked with vendors to purchase more recyclable materials including pipette tip boxes. Her labs also participate in vendor take-back programs, in which equipment manufacturers collect used items and donate or safely recycle them.

Fume Hoods

The single largest energy demand in lab buildings comes from chemical fume hoods, which are a staple of lab work. Fume hoods are used to protect researchers from dangerous materials or vapors by drawing contaminated air through a ventilation system. For safety reasons, these systems must run continuously 24 hours a day, whether or not they are actively being used. One energy-saving element of Variable Air Volume (VAV) fume hoods is their adjustable sash, which can be lowered or shut completely when they are not in use. This drastically reduces the energy demand of the ventilation system by slowing the fan. Many universities have designed “Shut the Sash” campaigns to educate lab personnel about the environmental benefits of this simple action.

Unfortunately for sustainability at Tufts, the vast majority of the SciTech building’s 50 VAV fume hoods have broken fan regulators, and are so old that replacement parts cannot be obtained. This means that shutting the sash on these machines does not reduce their energy demand. According to Edwards, it would be necessary to entirely replace many of the fume hoods to fix this issue, but funding is lacking. In contrast, the fume hoods in Ghosh’s labs are all equipped with automatic sashes, which use proximity sensors to open only when researchers approach. Ironically, this safety feature fails to save energy because the fume hoods at 200 Boston are not VAV, and therefore draw a constant amount of power regardless of their sash position. According to Ghosh, replacing these fume hoods with more efficient ones would cost millions of dollars.

Freezer Challenge

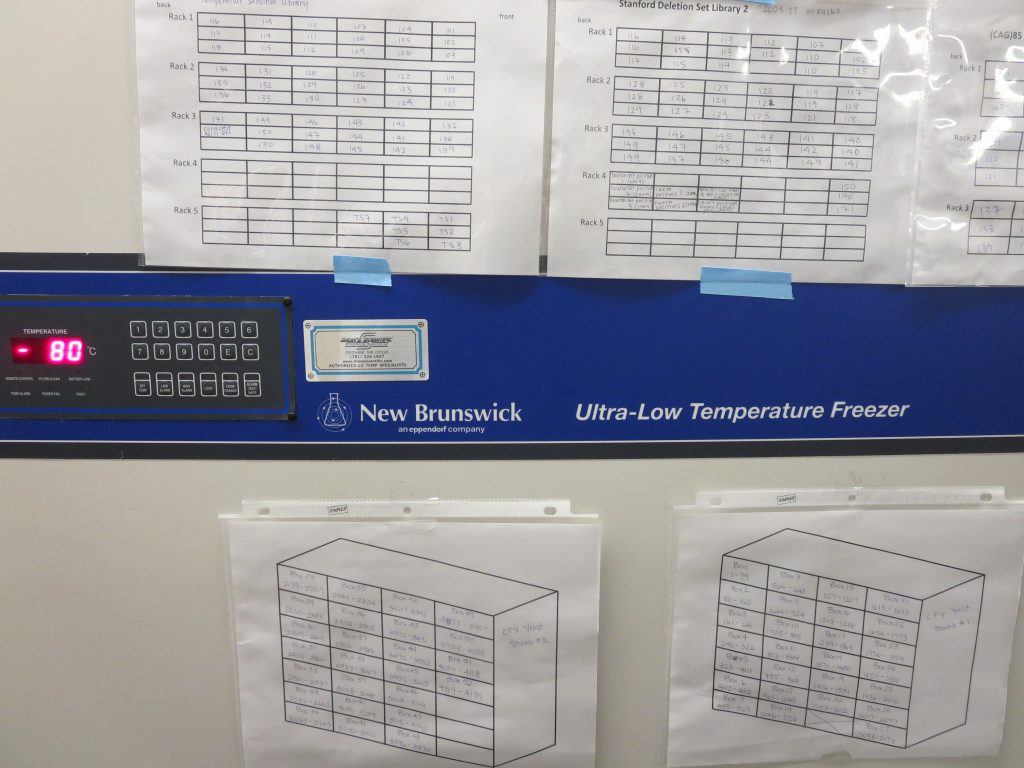

Another major energy draw for labs is refrigeration and cooling, as certain biomaterials must be stored in specialized freezers. “Ultra-low” freezers cool samples to -80 degrees Celsius (-112OF). The SciTech building has roughly eight of these ultra-low freezers in use, and Ghosh’s labs at 200 Boston have six.

Edwards and Ghosh both participated in the Freezer Challenge, a component of the Green Labs project, which set out to reduce the energy use of lab freezers. In order to operate each freezer more efficiently, a clear inventory of its contents was created, minimizing the time that the door needs to be open when searching for an item. The freezers also had to be regularly de-iced so that their doors could seal properly, keeping the heat out. Finally, it was important to remove unused items and consolidate partially full freezers, taking extra units offline when possible. At 200 Boston, old freezers have been gradually replaced with new, high-efficiency units, which use only one quarter of the power.

Other Initiatives

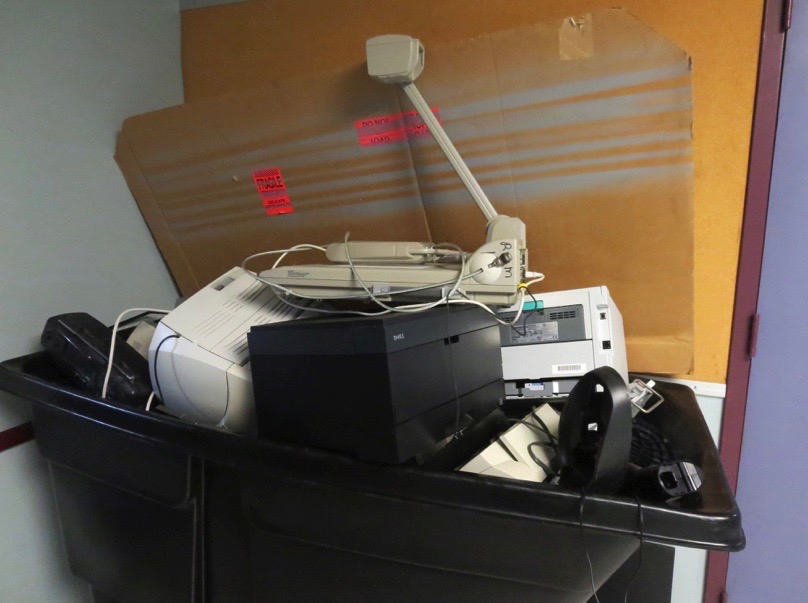

While optimizing the use of freezers and fume hoods may be the most direct way to increase efficiency, Edwards and Ghosh promote sustainability in other ways as well. Although recycling certain lab materials can be difficult, Edwards collects packing materials like Styrofoam and bubble wrap for reuse. SciTech has a dedicated recycling bin for electronics, which is used heavily when old workspaces are cleaned out. Ghosh also recycles all worn-out lab equipment, and donates functional equipment to other institutions, so virtually none of it ends up in the trash. In addition, Tufts sometimes receives donations from biotech companies, which is more sustainable and cost-effective than purchasing new equipment.

Tufts labs are making progress working towards their sustainability goals, but much work can still be done. Lab faculty, students, and administration must all collaborate to continue addressing the environmental impact of Tufts labs, thereby working towards a greener campus.

Find Us On Social Media!