Nutritional standards and quality certification of premixed infant cereals

Research in over 20 countries across Africa, Asia and Latin America suggests a new way to improve child nutrition, by setting standards and certifying the composition of premixed fortified cereals produced by local grain millers. Doing so could dramatically lower the cost and difficulty of delivering sufficient nutrients in a safe and convenient form during the crucial period of child development from 6 to 24 months of age.

After 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding, infants have outgrown the nutrients available in breastmilk alone but cannot yet digest a sufficient volume of other foods at family meal times. Premixed fortified infant cereals can fill the gap, allowing caregivers to boil up fresh porridge several times a day, ensuring nutrient balance and avoiding microbial contamination while gradually introducing everyday foods eaten by other family members at meal times.

A standard formula known as SuperCereal+ is used for infant foods that are donated in humanitarian emergencies and aid programs, but the commercial market for these products is largely unregulated. Parents are expected to meet infant needs from the same foods eaten by older family members. Preparing small quantities of high-density, easily digested baby foods is especially difficult between mealtimes, when specialized baby food is most useful.

Sampling and testing the foods currently being sold in 22 low- and middle-income countries reveals a very wide range of nutrient composition. Some of this variation is disclosed on the label, but in many cases the contents are not actually what’s advertised on the package. Test results show wide variation, both above and below the levels printed on product labels.

Introducing a common standard for premixed infant cereals would allow small and medium grain millers to enter the market with new products, competing on price and quality in their local markets. Since the mix of ingredients actually used cannot be detected by the buyer, an independent quality-assurance service is needed to ensure that each seller actually meets or exceeds the generic standard.

Recent work on this topic follows below:

- Trial results that fortified flours displace plain cereals, in MCN (2020).

- “First Foods” paper on infant diet quality, in Food Policy (Sept. 2019)

- IFPRI report on quality of infant foods in Malawi, with news story (July 2019) & slides for USAID (Oct 2019)

- World Bank ICABR presentation slides or PDF (June 2018)

- Microseminar video (7 min.) from Global Food+ symposium (Feb 2018)

- New York Times report on article in Maternal & Child Nutrition (Dec 2016) with photos of all packaging for 108 samples tested [reprint]

- Photo albums from infant-food tourism in Colombia (2017), Thailand (2018), Ghana (2018)

- Charlie Mace talk + video on paper-based testing for nutrients (2017)

- Friedman seminar presentation video, and slides in PDF and PPT (Feb 2016)

- Previous seminars such as slides and FASEB abstract of project results (spring and summer 2015), poster from the Micronutrient Forum in Addis Ababa (June 2014), and presentation slides at GAIN (June 2014), Tufts Medical School (Oct 2013), IFPRI (June 2013) and APHA (Oct. 2012).

- Scoping study in Ghana (2011): working paper and policy brief, presented in video + slides of seminar at Harvard School of Public Health (2011) and discussed in a short video (10 min) at IFPRI conference in New Delhi (2011), plus album of field photos (2010)

- Short summaries (2010): one-page concept note, and descriptions in the Tufts Journal and Tufts Nutrition magazine

History and links to publications on previous work

In this research, we ask whether child nutrition in developing countries could be improved by a program to test and certify the nutrient density of infant foods produced by local entrepreneurs. Currently, the infant-food market is dominated by high-priced products, like those being displayed by the pharmacist in the photo below.

These products are sold for many times the cost of nutritionally-similar alternatives developed by public health agencies. But when the lower-cost products are offered for sale, people rarely buy them. Our hypothesis is that people only buy the brand-name foods, even though they cannot afford enough quantity to meet their childrens’ needs, because they cannot observe these products’ nutritional content – so only a high priced brand name can be trusted at all. This kind of market failure was first described by George Akerlof, for which he shared the 2001 Nobel Prize in Economics.

Our research on this began with a market experiment in Bamako, Mali, measuring mothers’ demand for information about infant food quality. Our market experiment in offered women a variety of choices to elicit the tradeoffs they saw between the high-priced name brand, or a variety of other products including some whose quality is certified by Mali’s national food and agriculture research service.In our market experiment, mothers had an opportunity to make real choices between these products. This told us how much they care about various product attributes.

Mali, measuring mothers’ demand for information about infant food quality. Our market experiment in offered women a variety of choices to elicit the tradeoffs they saw between the high-priced name brand, or a variety of other products including some whose quality is certified by Mali’s national food and agriculture research service.In our market experiment, mothers had an opportunity to make real choices between these products. This told us how much they care about various product attributes.

|

|

|

Using the choices made by 239 women in and around the city of Bamako, Mali, we are able to calculate the value of quality certification. Using a rough budget for certification services, we estimated that the net welfare gains would be on the order of $20 per year per child of the relevant ages (6-24 months), which represents about one month’s worth of adequate nutrition for that child. The original research was funded by USAID, as part of a larger project on innovation in West African agriculture. The original publications, media coverage and a video about the research in Mali is posted below.

More recently, we tested the actual nutrient content of foods sold in 22 countries around the world, with results described in the most recent seminar video and article in Maternal and Child Nutrition as described in the New York Times’ Global Health column: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/19/health/baby-food-ingredients.html.

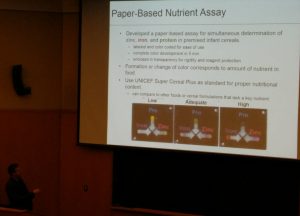

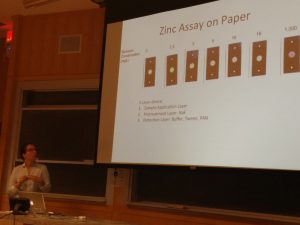

To facilitate the scale-up of new quality assurance systems, we are collaborating with chemistry professor Charlie Mace to develop much faster, less expensive and more robust methods of testing food samples for their nutrient content. Innovations in analytical chemistry could dramatically reduce the cost of testing, using techniques like the photo at right of Tufts undergrad Lauren Savage working on this project in mid-2016. Photos below are of Charlie presenting the latest prototypes at Harvard’s GlobalFood+ in February 2017. For insight into the future of quality assurance technology watch his whole presentation on a short 7-minute video!

To facilitate the scale-up of new quality assurance systems, we are collaborating with chemistry professor Charlie Mace to develop much faster, less expensive and more robust methods of testing food samples for their nutrient content. Innovations in analytical chemistry could dramatically reduce the cost of testing, using techniques like the photo at right of Tufts undergrad Lauren Savage working on this project in mid-2016. Photos below are of Charlie presenting the latest prototypes at Harvard’s GlobalFood+ in February 2017. For insight into the future of quality assurance technology watch his whole presentation on a short 7-minute video!

Citations and other links