Searching for Smugglers in Kabul, A Recollection

By Qiamuddin Amiry, under the supervision of Kim Wilson

While researching migrants and refugees, my former professor from graduate school had learned that Afghan migrants and refugees often used financial middlemen to facilitate their heavily smuggled journeys. She wanted to know more: Were financial middlemen likely to make a journey safer or more dangerous? How were migrants and refugees using those middlemen? And so on.

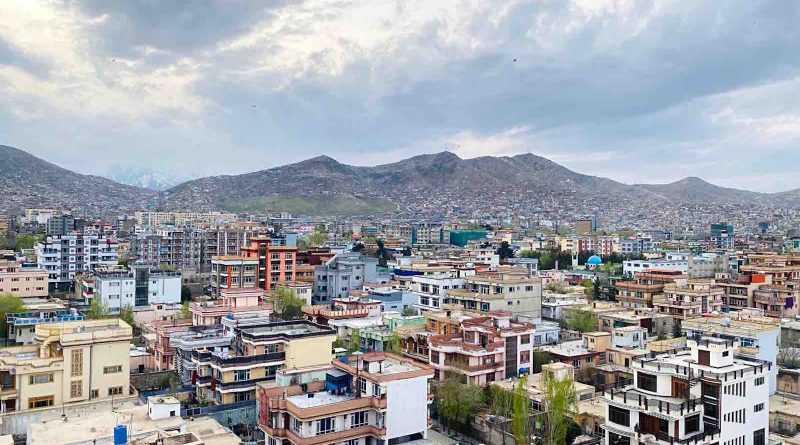

I was still living in Kabul. I had family members who had left the global south in search of better lives in the global north—some had even made it to Canada. I had journalist friends who had written about the subject, so I thought I knew a thing or two about migration. My professor asked if I would help her research. I said yes. Here are snapshots of what followed.

With a Nokia cellphone in his left hand, the money agent takes a step towards me and shakes a bundle of old floppy Afghani notes with his right. He leans in slightly and asks: “Chi dari? Dollar, kaldar, euro?” (Dollar, kaldar, euro, what do you have?) The on-foot money changers that populate the road to Sarai Shahzada, Kabul’s main money exchange market, think anyone walking towards the market might be looking to exchange money. I am not there to exchange money. They also top-up cell phone credits. I always thought they would be excellent “eyes” for the intelligence services, which is another reason why I continue walking without answering as he calls after me: “Aloo, chi bood?” (Which is it?)

On the sidewalk, sarafs (money exchangers) have arranged themselves more or less in a row, with their makeshift money tables in front. The entrance of the market is crowded enough that I allow the stream of human bodies to carry me inside. The sound of bundled money shaking and the cries of “Chi dari?” “Chi bood?” (What do you have, what was it?) swell as I enter.

While there are only 300 or so retail shops in the market, there are thousands of sarafs and traders. The way shops are stacked on top of one another and stairs squeezed into unusual places tell the story of sprawling and improvised growth. Outside shop 220 is a clutter of shoes. Next to the shoes, the pressure regulators of a pressure cooker spin madly. The smell of shorwa makes my stomach growl.

The retail space is miniscule. A man is counting money behind a cashier’s counter, which is right across from the entrance and spans the length of the shop. Two people, their backs to me, are standing in front of the counter. Just to the right, inside the shop, three men on a sofa are busy with their phones—one is playing Angry Birds. Facing the three men, I stand in a narrow space between a coffee table and the wall. This setting is not lending itself well to what I am about to ask.

After introducing myself to the men, whose eyes are fixed on their phone screens, I ask them what they might know about the roles of sarafs in helping Afghans migrate to Europe. I knew some things already, for instance, that sarafs would hold funds from families of migrants in trust (referred to as amanat in Farsi). The saraf would release the funds to the migrant’s smuggler when the migrant had safely reached a specified destination, for example Zahedan, Iran, or Istanbul, Turkey. Sometimes sarafs released funds multiple times over the course of one migrant’s journey. And sometimes only once. It was all negotiable. But, like my professor, I wanted to know more.

The man in the middle looks up. “Didn’t you see the banner outside? The government has banned sarafs from getting involved. It is illegal,” he exclaims as he goes back to his cell phone. “I saw the signs,” I tell him. “But just being illegal doesn’t really stop people from going about their business in this country,” I remind him. And I think to myself, there must be another reason he does not want to do business. Without responding to me, he looks at his friends with a smirk on his face.

I know that smirk. A week ago, I accompanied a friend, who was sending $5,000 to a relative in Canada, through a similar shop. Once that saraf was done counting the money and writing things down in his ledger book, he gave my friend a phone number to pass on to his relative. “Ask them to call this number to arrange the pick-up,” he said. Was that it? We just handed him $5,000 and all we got was a number? Unsatisfied, I said, “Can we get a proper receipt please?” He looked at people around him with a smirk, that smirk, the one I now understand to mean: “Can you believe this guy?” As it turns out, he was right and the money my friend sent his relative went through. But still.

When the man in the middle of the sofa finally looks up at me again, I know this conversation has ended. So I leave.

On the way to my office, the taxi driver and I are chit-chatting. He says that he is thinking of selling his car and joining his brother-in-law’s family as they journey abroad. Curious, I ask the taxi driver about his desired destination. “Wherever we end up. Greece. Germany . . . anywhere is better than here,” he responds. After a moment of silence, he tells me about a family that allegedly won more than 5,000 euros. The wife won a beauty contest at a refugee camp in Austria. He shared this story as a warm feeling washed over his face. Hearing this, I felt a shade of that smirk taking shape on my face too.

In the office I learn that our colleague, Najib, who cooks, cleans, and takes care of our two dogs has not shown up today. He has left for Iran with the hope of getting to Turkey. I remember him telling us that he had a friend in Turkey whom he had last seen more than 10 years ago. The friend would help Najib get to Turkey from Iran. One of our colleagues had asked Najib why he was not going to Germany instead. “All you need to do is cross Tajikistan and Germany is on the other side,” he suggested. The young cook was considering this suggestion when someone laughed. “So, he decided to go to Turkey instead of Germany,” I think to myself. This reminds me of a neighbor who had asked me whether he should give $3,000 to a travel agent who could get him a visa appointment with the US embassy. I had told him that appointments were free and they did not lead to visas. A couple of weeks later I learned that my neighbor had left for Germany with his wife and their three-year old son.

Back in my office, we order some food. As we wait for the take-out meal to arrive, I ask my colleagues whether they find it shocking that people can get up and leave on a whim. As my friends start sharing story after story, I realize that perhaps spontaneous journeys are the new normal. One colleague shares that their nephew disappeared a couple of weeks ago. A weeklong search involving police stations, hospitals, and ditches led to no sign of him. Then, the nephew called from Turkey. He had moved. Another colleague shares that she knows of a family that had traveled to Iran to cross into Turkey. Instead of walking with the little group the smuggler had assembled, the smuggler instead told the group which way to go—pointing them straight toward Iranian border police.

Tahir, our finance person tells me that one of his relatives could not bear the hardship of the journey and turned back. I then realize Tahir’s relative could tell me about his arrangement with the sarafs.

The next day, I am standing outside a building under construction. Two tall, slim guys come out after finishing a hard day of work. I recognize one of them. He is my colleague’s brother. The other one is introduced as Bashir. We go to a nearby ice cream shop and find a quiet corner. Bashir avoids eye contact. He has worn a vague smile on his face since we sat down. I can’t tell if he is amused, uncomfortable, or just happy. I ask Bashir how he found his smuggler. Bashir tells me he found him through a neighbor’s son who himself had made the trip to Turkey. Haji Karim is Bashir’s neighbor, a well-respected one at that. Haji Karim’s son had a tie to the smuggler as well as to Bashir and Bashir’s two cousins. The idea was that once the three cousins reached Turkey, Haji Karim’s son would find them another smuggler to move them through Turkey towards Europe.

When the three got to Nimrooz, Afghanistan’s only province that shares a border with Iran and Pakistan, they called a number supplied by the smuggler in Kabul. The number led them to a guide. As part of a group, they walked with the guide for three days to reach Pakistan. So, they had walked south to Pakistan and then west to Iran. When they finally found a ride, Bashir says he was one of sixteen people herded into a car that had room enough for five. Under pressure to move their human cargo, the local guide turned violent and beat them. Bashir had had enough and did not want to continue. So, he let his cousins go on toward Turkey and left the group, turning himself in to the Iranian border police. The next thing he knew, he was at a deportation camp, urdugah, waiting to be sent across the border back to Afghanistan. From there, he took a string of buses to Kabul.

For safekeeping, the cousins had not left the money designated for smuggling ($1,450 per person) with anyone. Instead, they pledged their uncle’s house in Kabul as a zamanat, or guarantee, to the smuggler. The understanding was that if the travelers arrived in Turkey and could not pay up, the smuggler had a right to sell the house. As it turned out, the two cousins arrived in Istanbul and paid the smuggler. The uncle said he never knew that his house at one point had served as collateral.

The next day, I visit a relative who has fallen sick: my mom’s cousin. Since my mom is in Tajikistan, it falls on me to go and say, “Get well soon!” The mood inside the room is heavy, and I gather that the old man’s deteriorating health is not the only cause. It turns out that the family’s youngest son, Amrullah, is in transit, on his way to Turkey. I had just recently become aware of the large numbers of people leaving Afghanistan. But suddenly, this once abstract concept of migration becomes very close. One-degree-o separation close. As I am thinking this, I realize migration has always been close to me. My family has been in Tajikistan for the past two years! Until that moment, I thought that migration was something other people did, something far removed from my reality. Now the more people I meet, the faster I see the distance between me and exiting Afghans disappear.

To console his mother, the older son, Ewaz, mentions that the smuggler is trustworthy. The juxtaposition of those two words don’t sit right with me. I look around to see if it has had the same effect on others in the room. Hard to tell. So I ask how they found a “trusted smuggler.” Ewaz explains that Amrullah’s smuggler had taken three “waves” of people from his neighborhood. This is the fourth. I half listen to someone in the room complain how it is not safe to walk in their neighborhood late at night, but I keep thinking of this third and fourth wave. I feel like something much grander should follow the word wave, like the third wave of feminism. But no, this wave is just about ordinary Afghans from a poor neighborhood in Kabul trying to leave town. At that moment, Ewaz receives a call from a relative. He is inquiring about the whereabouts of Amrullah, the youngest son, the one in transit. Ewaz explains that Amrullah had last called home from Quetta, Pakistan. “And yes, yes . . . yes . . . from there, they were going to Iran,” he says. I think of the route Bashir had taken. Kabul to Nimrooz, Nimrooz to Quetta, and Quetta to Iran. And I fight the urge to share Bashir’s story. I don’t want to add to their worries.

When I call a couple of days later, Amrullah has reached Istanbul. I want to learn about the rest of the route, but Ewaz doesn’t know. I can imagine that when one is facing a life-and-death situation, safety is the main concern, not the name of the place where he might inhale his last breath. Ewaz says that his brother had to stay with the smugglers until the family could put together the negotiated price of $1,200. “Stay with the smuggler” is a generous way of saying Amrullah was serving as collateral until the agent got paid. The $1,200 expected by the smuggler is $250 less than the cost Bashir had incurred during his passage. But I don’t articulate this on the phone, given that the Amrullah, only 17 years old, has been locked up for four days; the money has not yet been transferred to the smuggler’s agent in Istanbul. Before we get off the phone, Ewaz tells me that the fifth wave could not cross the border and turned back.

I ask my friend, Noor, who had introduced me to the money changer in shop 220, for the saraf’s number. I call the saraf and tell him that I hope I didn’t come across as rude with my questioning the previous day. The questioning that produced a smirk on his face. Hearing my conciliatory tone, he softens and says that there was trust at one point (between people migrating, the smugglers, and the money changers) but the trust has long since dissolved. I am enveloped in his words and want to know more. The saraf continues, “On many occasions, the passenger got to the destination only for the family to hear from the police that the passenger was lost in the Mediterranean. As you know, smugglers are hard to catch. They don’t disclose their addresses. They stay hidden from view. They conduct their business over cell phones—and the numbers keep changing. The saraf, the money agent, is the only one with a solid address.” I know this to be true. Sarafis, the money exchange stalls, are registered with the government. They have business licenses. Unlike smugglers, sarafs can be found. So, when the authorities need to go after someone, they know they will have better luck with a saraf than with a smuggler. When a few sarafs get pulle into court, others stop getting involved.

The next day, I tell Tahir, our finance person, about my phone conversation with the saraf and his take on trust among smugglers, sarafs, and migrants Tahir then tells me about a dealing he had with a saraf in 2011.

Back then, one of his friends was being smuggled. He was traveling to Sweden by air for a negotiated price was $22,000. Tahir was tasked with helping arrange the financing. Tahir knew someone named Shuja who knew the smuggler. Based on the smuggler’s advice, Shuja asked Tahir to “freeze” (hold) the money with a saraf in Sarai Shahzada, Kabul’s main exchange market. Tahir met with the saraf and the smuggler’s local agent. The saraf had a letter acknowledging the receipt of the money as an amanat, a kind of guarantee for the period of three months. Amanat refers to funds placed in trust with a third party.

The first time I heard the word amanat was under strange circumstances. At the height of the civil war in Afghanistan, a frail and quiet man in our neighborhood passed away. The family could not bury his body in the graveyard, which was on a hill. The graveyard was a strategic target for a fighting faction and thus bombarded regularly.

“What are they doing with the body?” I had asked. My mother said, “They have left it as an amanat with the soil in their courtyard, so that years from now when they can bury it in his final resting place, the body will be fresh and untouched.” I couldn’t help but ask my mother how the soil knew it was an amanat. To this, my mother gave me a no-more questions look.

In this situation, however, both parties knew the money was an amanat. Tahir wanted more concrete terms: the purpose of the money, the name of the traveler, his destination, and finally specific conditions under which the saraf would release funds to the smuggler. For the saraf, it was either a simple amanat, one without detailed instructions, or no deal. The saraf had taken the money, but, later, the deal between the smuggler and the traveler broke down. The traveler returned to Kabul from Dubai, without ever making it to Sweden. Shuja, the go-between, took $2,000 of the $22,000 fee (the travel tickets were extra) and returned $20,000 to the family.

I am learning more and more about the smuggling enterprise. Later, I meet with a friend of my brother, Tariq, who tells me his tale. He had won $4,000 on an Afghan TV show similar to Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? and planned to use it to leave Afghanistan. Tariq is married. Along with his wife, they had budgeted $3,000 for the smuggler’s fee. Tariq says that if passengers know one another and they travel as a group, the smuggler prefers that no sarafs get involved. When the group of 20 met, they agreed to leave their money with a trusted person in the neighborhood. That person would be responsible for transferring funds to the smugglers as the group safely reached certain destinations. In this case, the destination was Istanbul. The travelers made it to Nimrooz province, still in Afghanistan, where they got stuck for a week. They could not cross the border to Pakistan. They returned to Kabul and collected the money from the trusted designee. “The deal was: We get to Istanbul; the smuggler gets all the money. If not, we take back the money. It’s all or nothing,” Tariq tells me.

These stories lead me to believe I am right: The saraf system of guarantee is failing, not because it is illegal but because the business model is not working. Their fees, allegedly $1,200, is not a lot of money to keep in trust but it certainly can cause a lot of headaches. The alternative model of holding on to the passenger until his family has paid the smuggler works just fine. Human collateral is better than amanat because it gives some level of assurance to the family that they are in a “kar-tamam” deal, meaning that when the task is completed, the job is done.

QIAMUDDIN AMIRY

Qiamuddin is the Leadership Gift Officer at Colby College and a Fletcher alumn.

The author would like to thank the MetLife Foundation for supporting this research.

This publication was made possible in part by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

For questions contacts Kimberley Wilson at Kimberley.Wilson@tufts.edu