By Nery Calmo

Wandering through the bustling streets of Mexico City, I had no idea this trip would redefine my career path and open doors I never thought possible. During my time in CDMX, I embarked on a project examining the Mexican healthcare system, focusing on Indigenous communities and the impact of COVID-19. This project opened my eyes and showed me the importance of viewing the healthcare system from a perspective beyond the US lens. For example, while the US struggles with a physician and nurse shortage due to factors like debt and work-life balance, Mexico’s issue is not a lack of doctors but rather the need for better distribution across the country. This problem was exacerbated during the pandemic, highlighting the need for more efficient resource allocation and strategic planning to ensure that all regions, particularly rural and Indigenous areas, receive adequate medical care.

This project allowed me to dive deeper into a field of research I wasn’t previously aware of, exposing me to community health and the public health sector—areas often overlooked in the BSBME curriculum. By talking to doctors at the Cruz Roja Mexicana and leaders in Mexico’s public health field, I explored complexities and nuances I hadn’t known existed. I learned how policies and institutions have guided the country through the global pandemic, broadening my understanding and appreciation of this crucial field. For instance, I discovered how community health workers play a vital role in bridging the gap between modern healthcare systems and traditional practices, ensuring that culturally relevant care is provided to all populations in the country.

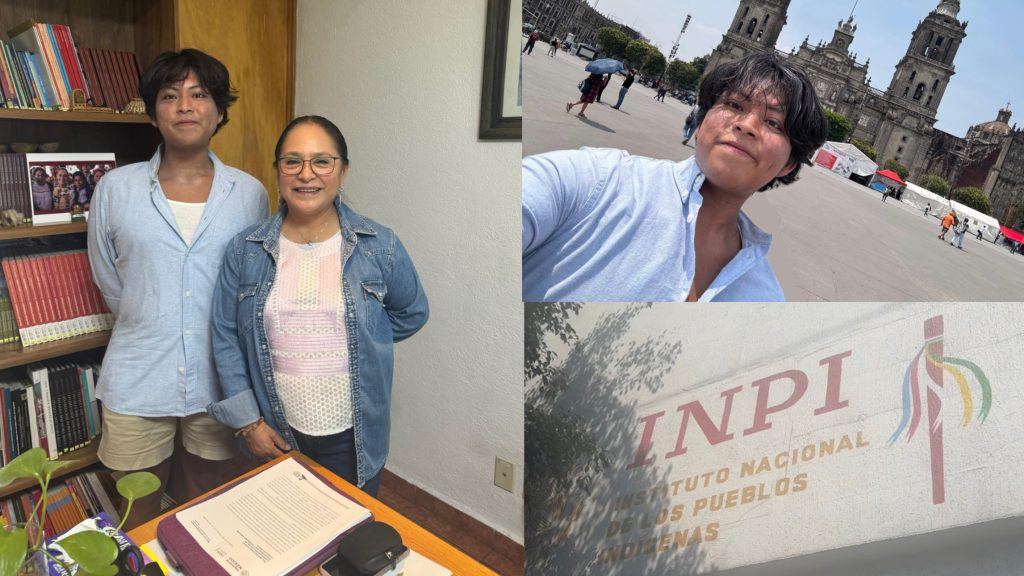

One of my main reasons why I wanted to explore this topic in particular is because of my background being Maya Mam and Guatemalan. After the genocide in GUA, many of my family members moved to Mexico to escape, leading to a significant portion of my family settling in the Yucatán. Due to Mexico’s proximity to Guatemala, I was eager to understand the healthcare systems and health policies in the country and how they impacted Indigenous communities like mine. Exploring Mexico’s response to the pandemic and learning more about institutions in place to help these communities such as INPI (Institución Nacional de Pueblos Indígenas), gave me a new avenue to explore and learn about. These institutions are crucial in advocating for Indigenous rights and ensuring that policies put in place are inclusive and supportive.

My interview with Dra. Bertha Dimas Huacuz at INPI was particularly inspiring as she aims to incorporate traditional medicines into medical education in Mexico to provide equitable healthcare for Indigenous communities, ensuring that their cultural practices are respected and integrated into modern healthcare. I was struck by the collaborative efforts of various organizations and government bodies in Mexico working towards a more inclusive healthcare system such as her initiative to train healthcare professionals in culturally competent care and the integration of traditional healing practices into public health strategies to address the needs of Indigenous populations and reinforce the importance of culturally sensitive healthcare. This conversation really resonated with me and revitalized my desire to hopefully one day attend medical school because it’s people like Dra. Dimas Huacuz who are not afraid to spark change that are worth looking up to; and gave me hope to one day do the same and give back to my community and finally heal from the traumas of the past.