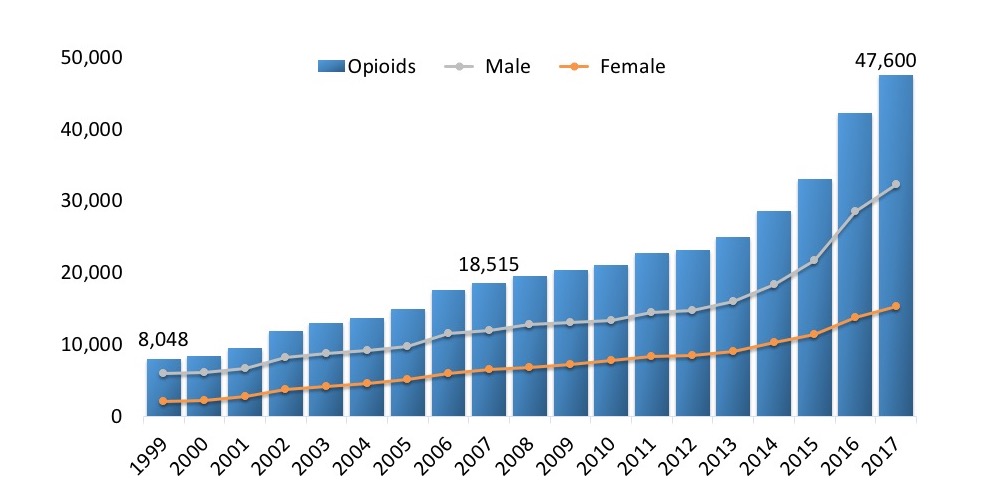

An average of over 130 people die of opioid overdose every day in the United States (6), a country that boasts a third of global opioid consumption but less than 5% of the global population (7), and one meta-analysis reported that 21-29% of patients who are prescribed opioids misuse them (8). These alarming statistics describe an ongoing American public health crisis known as the opioid epidemic. Beginning in the 1990s with an increase in opioid prescriptions from healthcare providers born of a combination of genuine and willful ignorance about their abuse liability (1), skyrocketing rates of opioid abuse and overdoses rapidly overtook the nation. The public sector has funneled substantial resources into a wide variety of attempted solutions, but the deaths continue to rise (Figure 4).

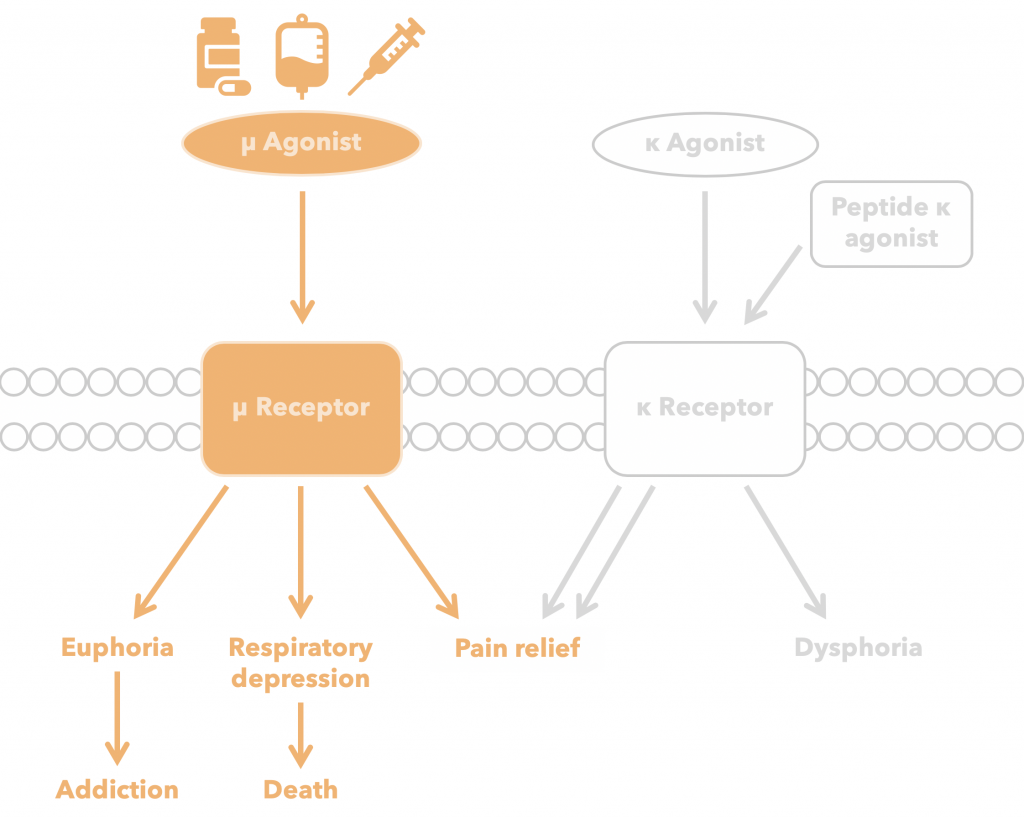

In the past decade, the predominant culprit of opioid overdose deaths has transitioned from prescription medications like morphine, oxycodone, and hydrocodone to highly potent, illicit derivatives sold on the street like heroin and fentanyl, although the former category still accounts for tens of thousands of fatalities (8). These are all small-molecule µ agonists, meaning they activate a neurochemical pathway that has potential for addictive euphoria and lethal respiratory depression. A major branch of the efforts against the epidemic is the development of opioids without these adverse side effects.

Even though small-molecule µ agonists’ abuse liability is ubiquitously recognized today, they remain the most prevalently produced and prescribed compounds for chronic pain treatment in the United States (1) . The need for continued investigation into alternatives is clear. While it is true that widespread adoption of a non-addictive analgesic by prescribers would not eradicate illicit opioids from the street, over 80% of heroin users begin with prescription opioid misuse (10), so formulating a non-addictive substitute would have substantial downstream as well as direct benefits. Although the opioid epidemic has many facets, it is indisputable that the addictive and lethal potential of small-molecule µ agonists are central to the problem, explaining the importance of the search for a non-addictive, safer alternative.

Figure 4 is very similar to the one on the answer page. The description for it makes a lot of sense regarding this pages contents, but the image itself I think I would change. This page is very informative about the history of the epidemic and pinpoints the main receptor responsible.

That makes sense! Using a modified version of this figure was originally suggested by Diren and Katie, and we think it highlights how the opioid crisis is fundamentally tied to the mu pathway. But thank you!

I thought an opioid crisis page would do well in the very beginning pages, so I suggest you move this to make it clear what question you are trying to figure out and solve.

See our previous reply.