How to bake pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo) empanadas

When I was growing up, my mom often bought pumpkin empanadas from El Aguila bakery in Fremont, Ohio. Let me tell you, there isn’t anything better with a hot cup of coffee.

As a kid, I never realized the important role pollinators play in creating these special treats. While many crops are pollinated by the wind (wheat, corn, rice), many fruits and vegetables are pollinated by insects. In fact, two important ingredients in my favorite empanada recipe benefit from animal pollinators.

Without insect pollinators, particularly bees, there would be no pumpkin, the main ingredient of the empanada filling. Pumpkin vines produce male and female flowers – this means that some flowers produce pollen, while other flowers bear fruits. Pollen from the anthers of male flowers must be deposited on the stigmas of female flowers for the vine produce fruit. Since pumpkin pollen grains are very heavy, pumpkin flowers cannot be pollinated by the wind. Instead, pollen grains must hitch a ride on a bee.

One of the cutest – and most important – pollinators of pumpkin are squash bees (Eucera pruinosa). Squash bees are solitary, ground nesting bees: a single female digs a nest for her offspring in the soil. Found in both the United States and Mexico, squash bees collect pollen exclusively from plants in the gourd family (genus Cucurbita), including pumpkin, zucchini, and summer squash. These little bees are super effective pollinators of squash plants, transferring up to 4 times as much pollen between flowers as honeybees.

Oranges, used to flavor the filling of empanadas, are another ingredient which can benefit from insect pollinators. Unlike pumpkin flowers, orange flowers are hermaphroditic: flowers can produce pollen and bear fruits. Orange flowers can be pollinated without help of insects if pollen from anthers is shed directly onto the stigma of the flower. However, orange flowers still are better off with bees than without. Without the help of an insect, flowers may be insufficiently pollinated, and will produce smaller and more acidic fruits. Sweet orange production is 35% higher for flowers visited by pollinating insects (like honeybees) compared to unvisited flowers.

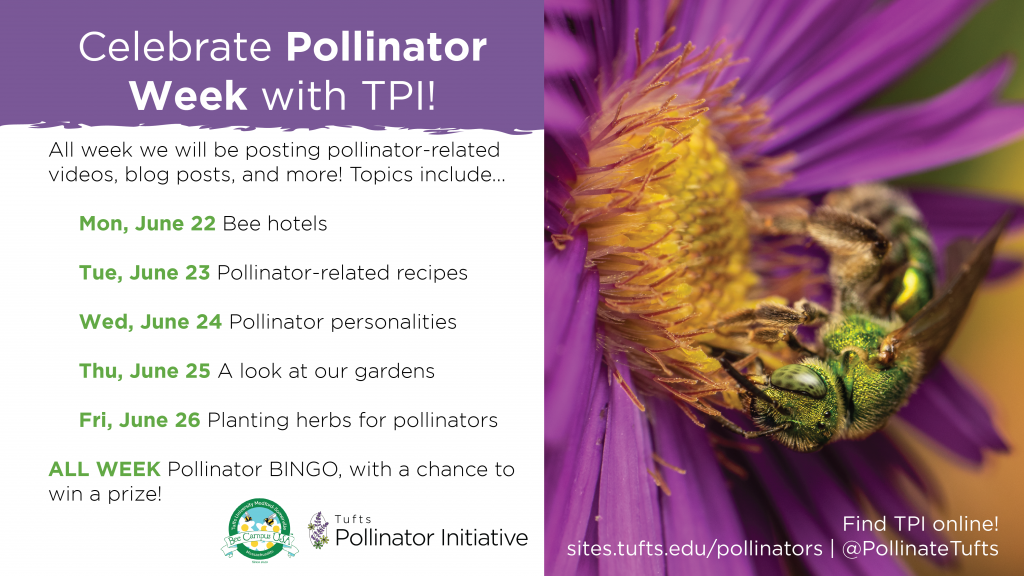

In honor of National Pollinator Week, I wanted to share with you one of my favorite recipes for pumpkin empanadas, modified from a recipe originally published by La Piña en La Cocina.

Pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo) Empanadas

Ingredients

For the Pastry:

- 2.5 cups all-purpose flour

- 1/4 cup cold butter

- 1/4 cup brown sugar

- 1/2 tablespoon active dry yeast

- 1 large egg at room temperature, lightly beaten

- 1/2 tablespoon cinnamon

- 2/3 cups warm milk (110 degrees F)

For the filling:

- 16 oz canned roasted and pureed pumpkin

- 1/3 cup brown sugar

- 6 star anise pods

- 1 cup of water

- 1 cinnamon stick

- 1 tablespoon orange juice concentrate

- Zest from one orange

For assembly

- 1/4 cup milk

- 1 lightly beaten egg white

Instructions

To prepare the pasty, sift flour into a large mixing bowl. Cut in butter, then cut in sugar, cinnamon, and yeast. Add the egg, and slowly incorporate milk until a dough forms. Knead for 6-8 minutes. The dough should be fairly sticky. If it is too dry, add more milk, and if it is too wet, add flour. Let rise about 2 hours.

To prepare the filling, boil star anise and the cinnamon stick in about 1 cup of water for about 10 minutes (or until about half of the water is evaporated). Add pumpkin, sugar, and juice concentrate to ¼ cup of this liquid, and cook until thickened, about 10-20 minutes. Let the filling cool in the fridge.

After the dough has risen, preheat the oven to 375 degrees F. Punch down the dough and divide into 1.5 oz balls. Roll out each ball until it is 4 inches in diameter. Place two tablespoons of filling in the center of the dough.

Brush the edges of the dough with egg white and fold the over dough and press out any air. Crimp the edges using a fork, or pinch to seal. Place the filled pastry on a greased backing tray. Repeat until all of the dough has been used. Once the pastries are all shaped, bush tops with milk. Bake for 20-25 minutes, until the pastry becomes a dark, golden brown. Makes 10-12 empanadas (which are best eaten within a day or two).

Enjoy! I hope you all have a very happy National Pollinator Week!

Citations:

Canto-Aguilar, M. A., & Parra-Tabla V. (2000). Importance of conserving alternative pollinators: assessing the pollination efficiency of the squash bee, Peponapis limitaris in Cucurbita moschata (Cucurbitaceae). Journal of Insect Conservation 4: 203–210.

Malerbo-Souza, D. T., Nogueira-Couto, R. H., & Couto, L. A. (2004). Honey bee attractants and pollination in sweet orange, Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck, var. Pera-Rio. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases 10(2): 144–153.