My Sites

Log in to create or edit your sites.

IMPORTANT SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENT: Content freeze 7am June 19th until 7am June 23rd. Read more here.

Need Help? Email edtech@tufts.edu

Site-Wide Activity

-

Kate Dahlgren wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 6 months ago

In 1988, Bobby McFerrin wrote a hit song based on words of wisdom from Indian mystic Meher Baba; the message was simple, “don’t worry, be happy.” The original music video for the song guest starred Robin Williams […]

In 1988, Bobby McFerrin wrote a hit song based on words of wisdom from Indian mystic Meher Baba; the message was simple, “don’t worry, be happy.” The original music video for the song guest starred Robin Williams […] -

Benjamin Heuberger wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 6 months ago

-

Gizem Altheimer wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 6 months ago

The focus of my blog posts so far has been on the relationship between threat-relevant attentional biases and social anxiety disorder (SAD). One way to test whether a certain process plays a part in the etiology of a disorder is to manipulate this process and examine the effect of this manipulation on the symptomatology. In this blog post, I will review several therapy-outcome studies that used attentional bias modification (ABM) training in patients with SAD.

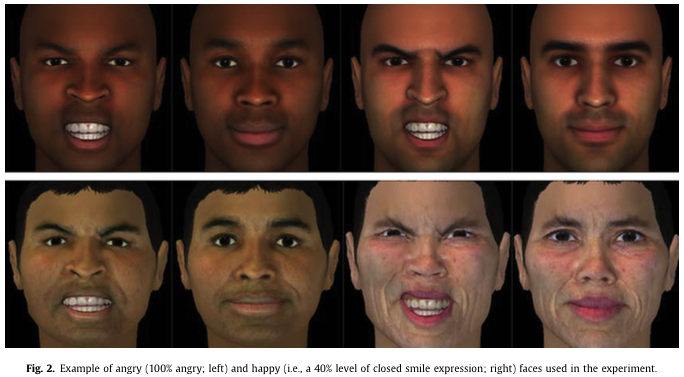

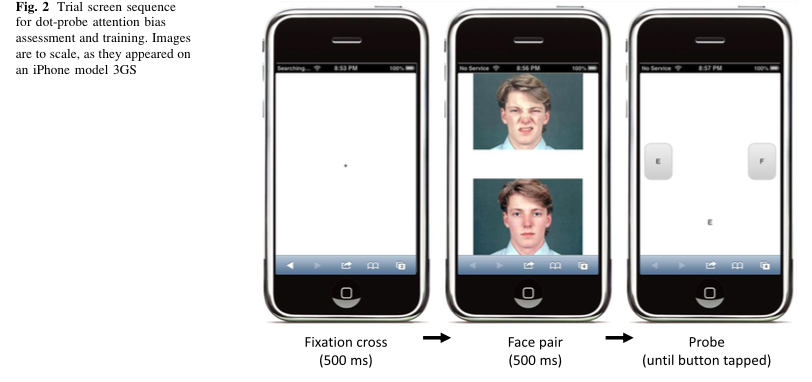

“What exactly is ABM training?” you may ask. In most cases, studies use a modified version of the dot-probe paradigm to reduce attentional bias for threat. As a reminder, during the original dot-probe paradigm, participants are first asked to stare at a fixation cross at the center of a computer screen. Then, two stimuli, one threatening and one neutral, appear on either side of the screen. After these stimuli are presented for a certain amount of time, a dot is presented at the location of one of the previous stimuli. Participants are then asked to report the location of this dot as quickly as possible through a button press. If a participant responds more quickly to dots after they have replaced threatening stimuli (compared to neutral stimuli), researchers conclude that the participant has vigilance to threat. During ABM training, the original task is modified in such a way that the dot probe nearly always replaces the neutral stimuli, therefore training the participant to attend to the non-threatening stimuli.

Although most studies to date have focused on the effect of ABM training on self-reported symptomatology of social anxiety (e.g. Amir, Beard, Taylor, Klumpp, Elias, & Chen, 2009) here I want to highlight a unique study by Heeren, Reese, McNally, and Philippot (2012) that investigated the subjective, behavioral, and physiological outcomes of ABM training toward and away from social threat. In this study, researchers randomly assigned participants with SAD to attend positive stimuli, threat stimuli, and to attend to both in alternating blocks (control) in an attempt to understand whether attention training is effective because of increased attention toward positive stimuli (and away from threat stimuli) or because of increased general attentional control (regardless of valence). After ABM training, participants were asked to give a speech during which researchers recorded behavioral (speech performance) and physiological (skin conductance) responses to stress.

Consistent with previous studies, participants who were trained to attend to positive stimuli reported greater reductions in self-reported social anxiety, both post-training and during a 2-week follow-up, compared to those who were trained to attend to threat stimuli and controls. They also reported greater reductions in behavioral manifestations of anxiety and physiological responses to the speech task. Control training only reduced self-reported distress at post-training.

Encouraged by this and many other studies that show positive outcomes in the lab, you might think: “Wow! Such a simple training and such positive results! Let’s make this more widely and easily accessible!” Well, if you have, you’re not the first one. Researchers have been exploring ways to make this type of training readily available and easily accessible to the public. Recent studies have developed versions of the training that can be administered via the Internet, however, disappointingly have not found encouraging results. Most studies I reviewed, be it ABM administered on a PC (Boettcher, Berger, & Renneberg, 2011; Carlbring, Apelstrand, Sehlin, Amir, Rousseau, Hoffman, Andersson, 2012; Neubauer, von Auer, Murray, Petermann, Helbig-Lang, & Gerlach, 2013) or a smartphone (Enock, Hofmann, & McNally, 2014) reported a decrease in SAD symptoms over time, but in both treatment and control groups; therefore were unable to attribute the changes to the training.

What might be some of the differences between administering this training in the laboratory setting compared to a real-world setting? Although this has not been empirically tested, researchers speculate that this may be due to several factors, such as: higher demand characteristics at a lab setting (although this doesn’t explain the physio findings), or inability to properly control the experiment, higher probability of distractions, or participants taking the task less seriously in the home setting. It is also possible that participants were in a state of higher anxiety and arousal in the lab, which somehow enabled their learning (Neuabauer et al., 2013).

Taking all of this in and going back to my initial question about whether threat-relevant attentional biases have a role in explaining the etiology of SAD, all we can say right now is that the evidence is inconclusive. Based on my earlier posts, there seems to be evidence that these biases exist in social anxiety, however the treatment studies outlined here where these biases are modified have given us disappointing results so far. To further these concerns, there are very few studies that use behavioral or physiological measures as indicators of change, and no neuroimaging studies to date that examine whether any changes occur in the brains of patients with SAD following ABM training.

And in terms of applications… for now, easily accessible and cheap internet-based ABM training seems like an exciting but somewhat disappointing treatment option for SAD. Perhaps we need therapists after all.

References:

Amir, N., Beard, C., Taylor, C. T., Klumpp, H., Elias, J., & Chen, X. (2009). Attention Training in Individuals with Generalized Social Phobia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(5), 961–973. doi:10.1037/a0016685.Attention

Boettcher, J., Berger, T., & Renneberg, B. (2011). Internet-Based Attention Training for Social Anxiety: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(5), 522–536. doi:10.1007/s10608-011-9374-y

Carlbring, P., Apelstrand, M., Sehlin, H., Amir, N., Rousseau, A., Hofmann, S. G., & Andersson, G. (2012). Internet-delivered attention bias modification training in individuals with social anxiety disorder–a double blind randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 66. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-12-66

Enock, P. M., Hofmann, S. G., & McNally, R. J. (2014). Attention Bias Modification Training Via Smartphone to Reduce Social Anxiety: A Randomized, Controlled Multi-Session Experiment. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38(2), 200–216. doi:10.1007/s10608-014-9606-z

Heeren, A., Reese, H. E., McNally, R. J., & Philippot, P. (2012). Attention training toward and away from threat in social phobia: effects on subjective, behavioral, and physiological measures of anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(1), 30–9. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2011.10.005

Neubauer, K., von Auer, M., Murray, E., Petermann, F., Helbig-Lang, S., & Gerlach, A. L. (2013). Internet-delivered attention modification training as a treatment for social phobia: a randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(2), 87–97. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2012.10.006

-

Joshua Manning wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 6 months ago

-

Victoria A. Floerke wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 6 months ago

Throughout my *undoubtedly* riveting blog posts I’ve talked a lot about positive emotions and how they aren’t always good for us. While the theories and findings I’ve discussed are fascinating, they’re also kind of (gasp!) boring. Wait, what? How can all of this paradoxical information concerning how wanting to feel good can sometimes be bad be boring, you ask? Well, the answer is really quite simple: almost all of these studies have been conducted on a relatively homogenous subset of people drawn from the broader American population (read: Caucasian college students). Wouldn’t it be even more interesting to understand how positive emotions work (and don’t work) across the globe? I certainly think so! Consequently, while we know very little about the cultural neuroscience of positive emotions (Hechtman, Raila, Chiao, & Gruber, 2013), we’ll spend this post getting up-to-speed on recent work concerning cultural variation in positive emotions.

Are Positive Emotions Universally Valued, Experienced, and Expressed?

Whenever you see someone smile, that probably means that they’re experiencing some type of positive emotion, right? That seems intuitive. But do people always smile when they’re happy? Furthermore, does the reason why people smile stay the same across cultures? Well, in a word, no. We know, for example, that American people report experiencing more individualistic types of positive emotions (e.g., pride), whereas Japanese people tend to report experiencing more interpersonal types of positive emotions (e.g., friendliness) (Kitayama, Markus, & Kurokawa, 2000). Other studies have additionally suggested that Western cultures tend to value experiencing more positive (relative to negative) emotions, whereas Eastern cultures tend to want to experience a balanced number of both positive and negative emotions (Uchida, Norasakkunkit, & Kitayama, 2004). These valuations aren’t meaningless, either; they affect important aspects of decision-making. Perhaps this explains why people who value high-arousal positive affect tend to choose high-arousal positive affect healthcare providers, whereas people who value low-arousal positive affect tend to choose low-arousal positive affect healthcare providers (Sims, Tsai, Koopmann-Holm, Thomas, & Goldstein, 2014).![It's [not such a] small world, after all[?] (Image retrieved fromhttp://farm3.static.flickr.com /2439/4040970541_dd77b982dc.jpg)](https://sites.tufts.edu/emotiononthebrain/files/2014/12/4040970541_dd77b982dc-199x300.jpg)

It’s not such a small world, after all? (Image retrieved fromhttp://farm3.static.flickr.com /2439/4040970541_dd77b982dc.jpg)

Although differences in self-reported positive emotion valuation are intriguing in and of themselves, it seems that these differences are also instantiated within the brain. People from individualistic and interpersonally-oriented cultures tend to activate their medial prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain implicated in self-focused thinking, more when they’re thinking about themselves in culturally-congruent (relative to culturally-incongruent) contexts (Chiao et al., 2009). Thus, it seems that people from different cultures have sociobiological reasons for wanting to feel differently, which may also lead to the differential experience of positive emotions across cultures.

It’s cool that people from different cultures tend to value and experience positive emotions differently, but how do they express their positive emotions to other people? Surprise, surprise: research suggests that cultural variation exists there, too. One study found that expressing positive emotions (e.g., smiling) when interacting with a same-ethnicity partner was related to lower blood pressure in European American women, but was associated with higher blood pressure in Asian American women, which suggests culture may affect our interpretation of emotional expressions during social interactions (Butler, Lee, & Gross, 2009). Yet another study demonstrated that when European American romantic partners converse they tend to experience either positive or negative emotions, whereas Asian American couples tend to experience both positive and negative emotions (Shiota, Campos, Gonzaga, Keltner, & Peng, 2010). Hence, positive emotions seem to be valued, experienced, and expressed differently across cultures.

What About Positive Emotion, Culture, and Psychopathology?

Given what you now know about the variation in valuing, experiencing, and expressing positive emotions across cultures, it’s perhaps unsurprising that positive emotions also differentially affect psychopathology cross-culturally. For instance, we know that depression is debilitating, but how it’s debilitating depends on culture. In the case of positive emotions, depressed European Americans tend to feel and express less positive emotions than non-depressed European Americans, but depressed Asian Americans tend to feel and express just as many positive emotions, if not more positive emotions, than non-depressed Asian Americans (Chentsova-Dutton, Tsai, & Gotlib, 2010). There’s also evidence that being raised in an individualistic or interpersonally-oriented culture is associated with carrying different forms of the serotonin transporter gene (specifically, 5-HTTLPR), which has been shown to predict the likelihood of developing certain affective disorders (Chiao & Blizinsky, 2010). Unfortunately, though it seems like positive emotions affect psychopathology differently across cultures, we know little else about how these differences arise, let alone how they affect subsequent treatment outcomes.

Fortunately, however, future cultural neuroscience studies could help us answer additional questions about how to cross-culturally treat various psychopathologies. In the case of Bipolar I disorder, we could ascertain whether European Americans (who tend to value more high-arousal positive affect) suffer from the disorder because of amplified reward sensitivity in the orbitofrontal cortex, as has been proposed (Hechtman et al., 2013). Relatedly, we could see whether Asian Americans (who tend to value low-arousal positive affect) with Bipolar I disorder may be more successful at activating circuitry related to down-regulating positive emotions than European Americans with the same disorder (Hechtman et al., 2013). We therefore have many avenues for future research that could shed light on treatment options for the global health crises psychopathologies present.

Wrapping It All Up

So what’s the take-away point from today? Well, obviously, I hope you learned that, while there is little evidence concerning the cultural neuroscience of positive emotions, there is cultural variation in the extent to which people value, experience, express, and, yes, sometimes even suffer from positive emotions. More broadly, though, I hope you come away from these blog posts with a sense that positive emotions are not universally good for everyone, all the time, in every context. If we remember that I think the world could become a much happier (but not necessarily smaller!) place.

References

Butler, E.A., Lee, T.L., & Gross, J.J. (2009). Does expressing your emotions raise or lower your blood pressure? The answer depends on cultural context. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40(3), 510-517.

Chentsova-Dutton, Y. E., Tsai, J. L., & Gotlib, I. H. (2010). Further evidence for the cultural norm hypothesis: Positive emotion in depressed and control European American and Asian American women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(2), 284-295.

Chiao, J. Y. & Blizinsky, K. D. (2010). Culture-gene coevolution of individualism-collectivism and the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277(1681), 529-537.

Chiao, J. Y., Harada, T., Komeda, H., Li, Z., Mano, Y., Saito, D., … & Iidaka, T. (2009). Neural basis of individualistic and collectivistic views of self. Human Brain Mapping, 30(9), 2813-2820.

Hechtman, L. A., Raila, H., Chiao, J. Y., & Gruber, J. (2013). Positive emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic cultural neuroscience approach. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 4(5), 502-528.

Kitayama, S., Markus, H. R., & Kurokawa, M. (2000). Culture, emotion, and well-being: Good feelings in Japan and the United States. Cognition & Emotion, 14(1), 93-124.

Shiota, M. N., Campos, B., Gonzaga, G. C., Keltner, D., & Peng, K. (2010). I love you but…: Cultural differences in emotional complexity during interaction with a romantic partner. Cognition and Emotion, 24(5), 786-799.

Sims, T., Tsai, J. L., Koopmann-Holm, B., Thomas, E. A., & Goldstein, M. K. (2014). Choosing a physician depends on how you want to feel: The role of ideal affect in health-related decision making. Emotion, 14(1), 187-192.

Uchida, Y., Norasakkunkit, V., & Kitayama, S. (2004). Cultural constructions of happiness: Theory and empirical evidence. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5(3), 223-239.

-

Aleksandra Kaszowska wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 6 months ago

Throughout this semester, I have explored the science behind issues all (graduate) students face in their daily emotional lives. I talked about what studying neuroscience actually entails, how caffeine consumption […]

Throughout this semester, I have explored the science behind issues all (graduate) students face in their daily emotional lives. I talked about what studying neuroscience actually entails, how caffeine consumption […] -

Giovanna Castro wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 6 months ago

-

Irina Yakubovskaya wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 6 months ago

In this week’s blog, I am exploring theatrical activity and its potential risk of perpetuating mental disorders. I am also suggesting that creativity in general is considered inherently risky because of its […]

-

Amy M. Smith wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 6 months ago

This being my final blog post, I’d like to start off by providing you with an eloquent summary of what I covered in posts 1, 2, and 3. Here it is:

stress hates your brain.

…but seriously. Though it is unclear how acute stressors (like having to give a speech in front of an audience) impact brain structures, the literature has converged on the finding that increased stress hormones after acute stress result in a poorer ability to retrieve memories. And then there’s the whole chronic stress literature, which points to the fact that chronic stress depletes brain regions associated with memory like the hippocampus and PFC. But we all experience stress, right? And some of us (*cough*grad students*cough*) may even feel chronically stressed. So what can we do to reduce our reactions to stress, and hopefully save our brains from its unwanted consequences?

Thankfully this is a question people have been asking for a long time, and researchers and clinicians have come up with some answers. In my final post on the topic of stress and the brain, I’d like to introduce you to the popular mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) technique, discuss its effectiveness at reducing stress, and explain how associated brain changes may contribute to its success.

MBSR is a meditative technique in which people are trained to be open-minded and non-judgmentally aware of their moment-by-moment physiological and psychological experiences (Nyklíček & Kuijpers, 2008). For example, in a stressful situation, a person engaging in MBSR may consciously acknowledge, “my heart is beating fast” instead of thinking, “my heart is racing and that is a really bad sign.” Mindfulness meditation is rooted in the Buddhist belief that psychological distress stems from the tendency for our judgmental minds to label our life experiences as good or bad (Nyklíček & Kuijpers, 2008). According to this philosophy, by eliminating this good/bad labeling via mediation that encourages us to consciously recognize this behavior, MBSR should improve our psychological well being.

During MBSR training, participants typically meet with instructors on a regular basis for eight weeks, and are also expected to engage in mindfulness meditation on their own time at home (e.g., Nyklíček & Kuijpers, 2008). These training techniques have been shown to successfully reduce self-reported stress, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and rumination (for a meta-analysis see Chiesa & Serretti, 2010). MBSR techniques have even been shown to improve people’s overall quality of life, as measured by satisfaction with factors such as physical health, psychological health, and social relationships (Nyklíček & Kuijpers, 2008).

Here’s a summary of what we’ve learned thus far:

With regard to the neural mechanisms underlying MBSR, both immediate brain changes during MBSR and long-lasting brain changes as a result of chronic MBSR may shed light on why this technique is so effective.

Brain changes during MBSR:

Ives-Deliperi, Solms, and Meintjes (2011) compared fMRI brain activation during resting versus during mindfulness meditation for people who were well-trained in MSBR. They found that, when participants engaged in meditation, they demonstrated decreased activity in the anterior insula, left ventral anterior cingulate cortex, right medial prefrontal cortex, and bilateral precuneus. In case you, like me, are not a neuroscientist, it may be helpful to know that those structures have been roughly implicated in self-referential thought. The authors further supposed that the reduced activity may have been indicative of disidentification, which happens when people temporarily suspend their sense of self, including all habitual thoughts and behaviors. Theoretically, during disidentification, thoughts that enter the mind are registered in the absence of judgment. Though mostly speculative at this point, these findings do provide support for a neural basis for the effectiveness of ongoing MBSR, in the form of reduced activity in brain regions associated with subjective assessments of the self.

Brain changes after MBSR:

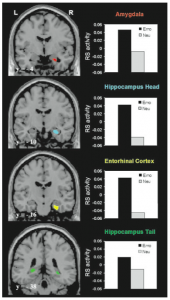

Holzel et al. (2010), recruited participants who reported high levels of stress for at least a month to complete an eight-week mindfulness training program. Participants underwent MRI scanning before and after training. At the post-training scan, participants’ subjective reports of reduced stress were correlated with reduced grey matter density in the right basolateral amygdala. Again, in case you’re no neuroscientist, one process that the amygdala is associated with is our automatic emotional response to stimuli. Thus, the authors hypothesized that reduced density in the amygdala indicated that MBSR influenced an individual’s initial reaction to stimuli, perhaps by discouraging individuals from emotionally overreacting.

Okay, so we (and a wealth of literature) can agree that stress is the worst and can really mess with our ability to remember information. But thanks to the MBSR technique, there is hope! Not only have several researchers demonstrated that MBSR is incredibly successful at reducing subjective stress (see Chiesa & Serretti, 2010), but even our brains show evidence of its ability to calm regions associated with self-judgment and emotional reactivity. Moral of the story? Mindfulness works. Yeah science!References

Chiesa, A., & Serretti, A. (2010). A systematic review of neurobiological and clinical features of mindfulness meditations.Psychological Medicine, 40(8), 1239-1252.

Hölzel, B. K., Carmody, J., Evans, K. C., Hoge, E. A., Dusek, J. A., Morgan, L., . . . Lazar, S. W. (2010). Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 5(1), 11-17.

Ives-Deliperi, V., Solms, M., & Meintjes, E. M. (2011). The neural substrates of mindfulness: An fMRI investigation. Social Neuroscience, 6(3), 231-242.

Meme Mindfulness works! yeah science! (n.d.). Retrieved December 7, 2014, from http://hotmeme.net/post/yrI/mindfulness-works-yeah-science/

Nyklíček, I., & Kuijpers, K. F. (2008). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention on psychological well-being and quality of life: Is increased mindfulness indeed the mechanism? Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 35(3), 331-340.

-

Lindsay A. Hinzman wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 6 months ago

-

Tegan Kehoe wrote a new post on the site Museum Studies Blog at Tufts University 10 years, 6 months ago

A little over a month ago, I posted some of my own reactions to participating in the Slave Dwelling Project’s overnight at the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford.

-

Rebecca Rago wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 6 months ago

Welcome back! I have some sad news for you, dear reader, this is going to be my final blog post on emotion and the senses (cue tears). My past entries were on senses in general, vision, and hearing. This week will […]

Welcome back! I have some sad news for you, dear reader, this is going to be my final blog post on emotion and the senses (cue tears). My past entries were on senses in general, vision, and hearing. This week will […] -

esefik01 wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 6 months ago

No Treatment for Negative Symptoms?

“You really have to look for sad mood to identify depression,” says Douglas Noorsdy, Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Dartmouth University. “Patients with schizophrenia will usually describe a lack of emotional expression and a blah feeling, whereas in depression they’ll have an actively depressed mood.”

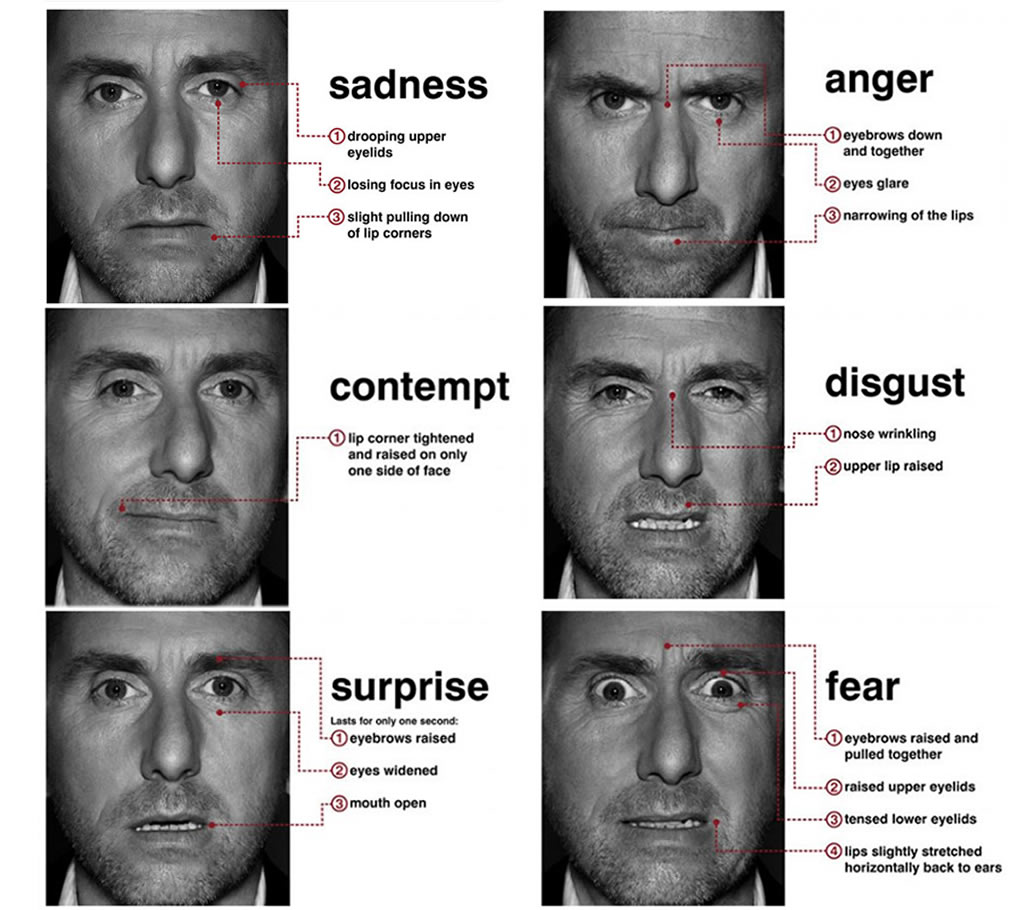

Negative symptoms: A decrease or loss of normal functions, such as a loss of energy, motivation, and emotional display of affect

This lack of emotional expression and “blah feeling” that Dr. Noorsdy is describing is an example of the problematic domain of signs and symptoms of schizophrenia called negative symptoms. As I have explained in my first blog post, the “negative symptom” terminology refers to a decrease or loss of normal functions, such as a loss of energy, motivation, and emotional display of affect. Here, it is important to distinguish between lack of expression and lack of feeling because when questioned, patients with schizophrenia often express a full range of feelings and desires (Kring et al., 1993). The difference between what they may feel and what they show has to be taken into account in deciding whether or not the patient is suffering from depression or from the negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

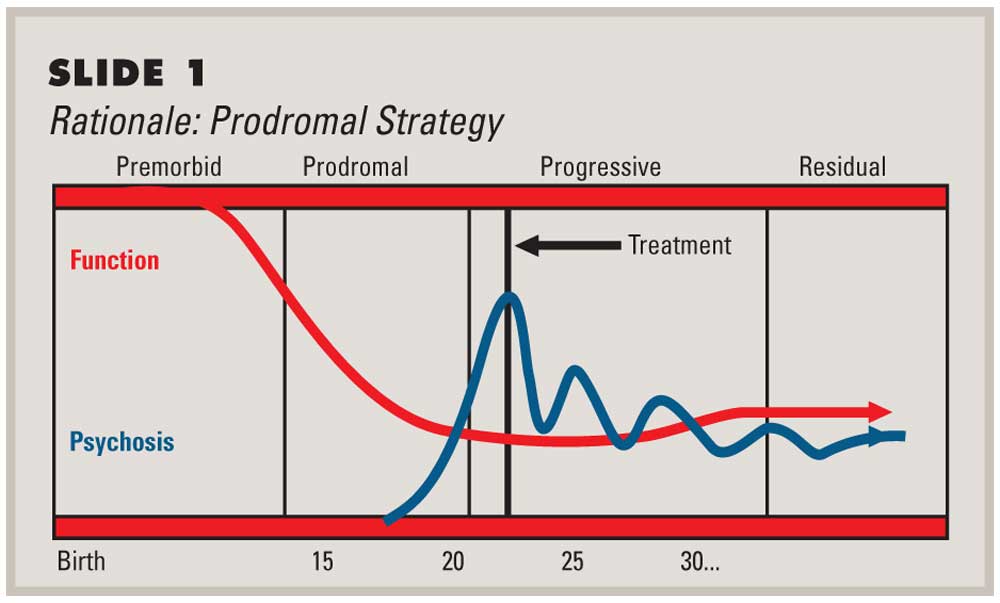

According to the Harvard Medical School’s Family Health Guide on Schizophrenia, “negative symptoms tend to be more stable than positive symptoms, and commonly begin to emerge very early in the course of schizophrenia, even before the development of positive symptoms.” In fact, negative symptoms often first appear during the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. During this phase, which can last weeks or months, people start to withdraw from friends and family members and begin to lose interest in their usual pursuits. Hence, emotion deficits characterize this period and tend to be misunderstood as signs of laziness rather than illness.

In this blog post, the question I will aim to answer is: How debilitating are these negative symptoms and how effective are currently prescribed antipsychotics in their treatment?

Prodromal phase: Schizophrenia usually starts with this phase, when symptoms are vague and easy to miss. They are often the same as symptoms of other mental health problems, such as depression or other anxiety disorders.

Positive symptoms of schizophrenia, such as hallucinations and delusions, make treatment seem more urgent, and they can often be effectively treated with antipsychotic drugs. But negative symptoms are the main reason patients with schizophrenia cannot live independently, hold jobs, establish personal relationships, and manage everyday social situations. These symptoms are also the ones that trouble them most. Surveys find that “the chief concerns of schizophrenic people are difficulty in concentrating, thinking, socializing, and enjoying life” (Shtasel et al., 1992). Schizophrenia’s negative symptoms have traditionally been viewed as treatment-resistant, but recent studies show that they do respond to pharmacologic and social interventions.

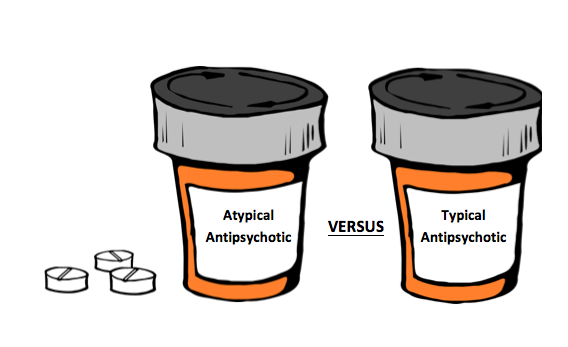

In 2003, Moller et al. published a systematic review of previous literature focusing on the pharmacological treatment of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Their purpose was to contrast and combine results from studies (published between 1995 and 2002) that compared the efficacy of typical and atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Their results indicated that atypical antipsychotics, such as clozapine and olanzapine are more effective in treating negative symptoms of acute schizophrenic episodes than typical antipsychotics such as haloperidol. As evident in the findings of Moller et al.’s meta-analysis, clinical studies in patients with schizophrenia suggest that second generation neuroleptics are more effective than typical neuroleptics in reducing negative symptoms such as anhedonia and flat affect.

So, here the question is: What makes atypical antipsychotics more effective?

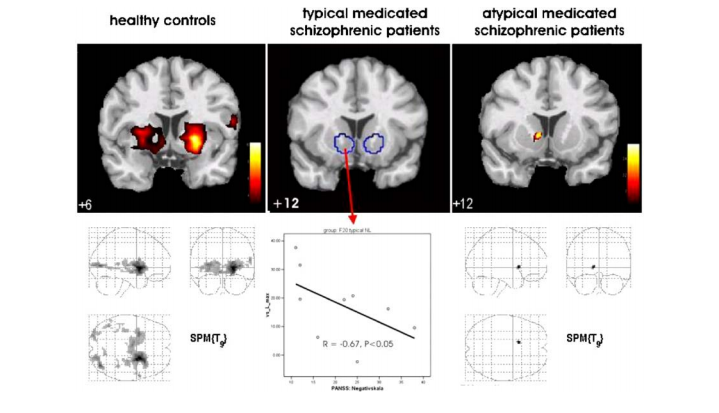

Previous literature suggests that dysfunction of the ventral striatum, thus, the dopaminergic reward system may contribute to the development and persistence of negative symptoms in schizophrenia (Heinz et al., 1998). According to this hypothesis, atypical antipsychotics are more effective in treating negative symptoms because they significantly reverse the blunting of ventral striatal activation.

Juckel et al.’s 2006 fMRI study aimed to test this hypothesis by assessing ventral striatum activation in 10 schizophrenics taking typical antipsychotics, 10 schizophrenics taking atypical antipsychotics and 10 healthy control subjects during an incentive monetary task. Their results indicated that healthy control subjects and patients taking atypical antipsychotics showed a significant increase in BOLD response in their ventral striatum during anticipation of potential monetary gain, while patients taking typical antipsychotics did not.

They also found that decrease in the activation of the ventral striatum was correlated with the severity of negative symptoms. Less striatum activation meant more severe negative symptoms. In summary, significant blunting of ventral striatal activation was not observed in patients treated with atypical neuroleptics, which reflects the improved efficacy of these drugs in treating negative symptoms.

Ventral striatum activation during an incentive monetary task: healthy controls > atypical medicated schizophrenic patients > typical medicated schizophrenic patients

To conclude, negative symptoms represent an important treatment target in schizophrenia. In recent years, our understanding of these symptoms has benefited greatly from the adoption of methods from the field of affective neuroscience. Scientific findings suggest a role for second-generation antipsychotics in reducing the debilitating effects of negative symptoms, but we have yet to find the ultimate cure for emotion deficits in schizophrenia. Demystification of schizophrenia, along with recent insights from neuroscience and neuropsychology, gives new hope for finding more effective treatments for those suffering from this illness, who were once thought to be possessed by demons and were feared, tormented or locked up forever.

Sources:

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. (2013). Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association.

Shtasel DL, Gur RE, Gallacher F, Heimberg C, Cannon TD, Gur RC. Phenomenology and functioning in first episode schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 1992;18:449-462.

Moller HJ. Management of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia: new treatment options. CNS Drugs 2003;17: 793:823.

Juckel G, Schlagenhauf F, Koslowski M, Foliniv D, Wustenberg T, Villringer A, Knutson B, Kienast T, Gallinat J, Wrase J, Heinz A. Dysfunction of ventral striatal reward prediction in schziophrenic patients treated with typical, not atypical, neuroleptics. Psychopharmacology 2006; 187: 222-28.

Fig 1: http://www.thementalelf.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/shutterstock_81409651.jpg

Fig 2: http://www.cnsspectrums.com/userdocs/articleimages/86/1007Perk1big.jpg

Fig 4: Moller HJ. Management of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia: new treatment options. CNS Drugs 2003;17: 793:823. -

Lila Kohrman-Glaser wrote a new post on the site Emotion, Brain, & Behavior Laboratory 10 years, 6 months ago

-

Rebecca Boehm wrote a new post on the site Tea & Climate Change Collaborative 10 years, 6 months ago

Recently, our team published a manuscript in the Journal of Chromatography summarizing the effects extreme weather events have on tea plant physiology. Comprehensive volatile metabolite libraries were produced for teas harvested before and after the East Asian Monsoon in SW China using automated sequential, multidimensional gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC-GC/MS). Using this technology, we were able to identify a total of 201 spring and 196 monsoon metabolites, with 169 common and 59 seasonally unique compounds. Spectral deconvolution of GC/MS data using the metabolite libraries showed marked seasonal differences. Striking concentration differences were observed within families in as little as 5-days after the monsoon onset, with individual metabolites increasing, decreasing or remaining the same between the seasons. The analytical methods developed in this paper will be used to profile metabolites in tea over time with respect to harvest season and climate.

Questions? Please contact the corresponding author on this manuscript, Dr. Albert Robbat, Jr. (albert.robbat@tufts.edu) -

Eujene Yum wrote a new post on the site Sustainability at Tufts 10 years, 6 months ago

Position:

The Water Program is hiring a Program Assistant to support this thriving and growing team. This job is an opportunity for an organized, detail-oriented, and mission-driven individual. This is a […]

-

Sarah Gibbons is attending Seminar III. 10 years, 6 months ago

-

Rebecca Philio wrote a new post on the site What's New @ HHSL 10 years, 6 months ago

-

Joann O’Brien is attending Seminar III. 10 years, 6 months ago

-

Lauren Martin wrote a new post on the site Sustainability at Tufts 10 years, 6 months ago

Spring Internship with MyRWA!

The Mystic River Watershed Association (MyRWA) seeks a GIS Intern to assist in a project investigating relationships between water quality data from stormwater systems and features of stormwater infrastructure, land use, population, and other variables. The GIS intern may be asked to assist in other data projects, if appropriate.

The GIS Intern will develop, edit, verify, and analyze spatial data related to drainage basins, municipal stormwater infrastructure, and water quality within the Mystic River Watershed. Experience with ArcGIS software and fluency with Excel are required.

Interns will learn about efforts that a watershed association undertakes to advocate for water quality improvements. The intern must be able to work independently and as a team. This is a part-time position that requires a commitment of two to three days a week during the Monday through Friday work week. Position begins in January and concludes mid-April – exact dates can be flexible depending on the candidate.

An interest in science, the environment and advocacy is encouraged.

This is an unpaid position.

Since 1972, MyRWA has played a unique role in the whole of the watershed by its science, advocacy, and outreach efforts. The Mystic River Watershed Association is based in Arlington, MA and is accessible via several bus routes. The Mystic River Watershed Association is an equal opportunity employer.

If interested, please send your resume to WQInternship@MysticRiver.org. No phone calls please.

Deadline for application: January 4, 2015. - Load More