Israel After October 7 and the War on Gaza

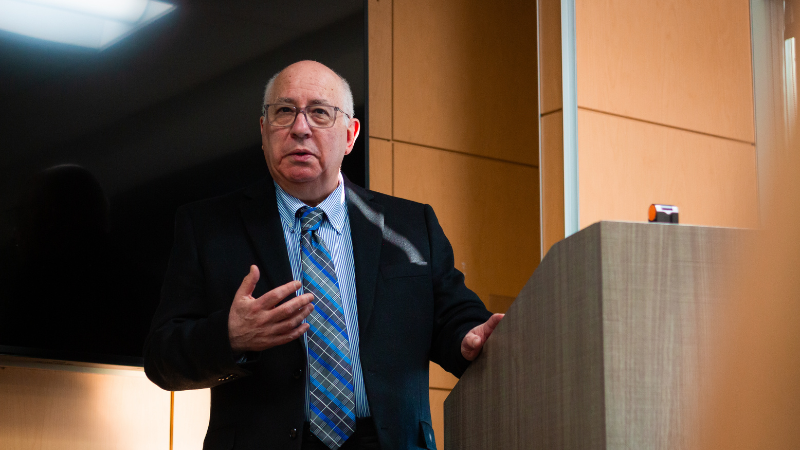

On March 11, 2025, the Fares Center hosted Professor Shai Feldman, Raymond Frankel Chair in Israeli Politics and Society at the Crown Center for Middle East Studies and Professor of Politics at Brandeis University. Professor Feldman’s analysis offered a structured breakdown of the multiple failures leading to and arising from the October 7 attacks. He identified four areas that played a central role in the lead-up to October 7 and the subsequent war.

First, he discussed how previous diplomatic efforts, primarily those led by the United States, have failed to resolve Israeli-Palestinian tensions, creating a diplomatic vacuum. He argued that these past failures have allowed long standing grievances to erupt into violence. Second, he examined the impact of regional developments, focusing primarily on Hamas’s deepening relationships with other Iranian-backed groups in the region. Third, Professor Feldman discussed political instability within Israel. He presented the judicial overhaul crisis as a domestic conflict that left Israel’s deterrence posture exposed leading up to October 7. Finally, he explored the role of shifting dynamics within Palestinian leadership, calling attention to the weakened position of the Palestinian Authority (PA) and the parallel ascendency of Hamas.

Professor Feldman concluded with a discussion on the future of peacemaking in the Israel-Palestine conflict, asserting that the two-state solution remains the sole viable endpoint. Furthermore, he underscored that no durable resolution—whether two-state or otherwise—can emerge without broad international engagement, particularly from Arab powers.