A New Reality in Northern Syria: The Geopolitics of Trump’s Syria “Withdrawal”

by Caleb Weiss ’21 and Nathan Heath ’20

Intro

In recent months, the geopolitics of the Syrian Civil War have shifted yet again. In mid-October, the Trump administration announced that U.S. forces would withdraw from Syria, a tactical move that opened the door for Turkey to launch a military offensive into Northern Syria as part of a security operation to protect its homeland from alleged Kurdish terrorist groups such as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). The Trump administration’s decision to withdraw has sparked significant backlash in the U.S. and around the world, resulting in increased destabilization within Syria and new geopolitical maneuverings from the larger powers participating in the conflict.

Geopolitical Shifts

The U.S. withdrawal paved the way for the Erdogan regime to launch a military offensive against Kurdish fighters in Northern Syria. On October 10, Turkish forces initiated a combined ground and air campaign against targets such as Kobani, Ras al Ain, and Akcakale, killing hundreds of Kurdish fighters and civilians. On October 11, Turkish forces reportedly fired on U.S. forces embedded with Kurdish fighters in the vicinity of Kobani.

Although the incident was clarified to be a mistake, U.S.-Turkish relations, already strained from Turkey’s purchase of S-400 missiles from Russia, U.S. tariffs on Turkish imports, and the detention of Pastor Andrew Brunson, have worsened since the offensive against the Syrian Kurds began. U.S. Vice President Mike Pence purportedly negotiated a now-defunct ceasefire with Erdogan on October 17, and the Turkish president paid a visit to Washington, D.C. on November 13.

In addition to Turkey, other regional and global powers are quickly taking advantage of the U.S. forces drawdown to increase their presence in Syria. Despite not having a formal alliance, Russia and Iran have had an active military presence in the country since September 2015 and early 2011, respectively. Russia, whose principal tactical approach has been the use of airstrikes reportedly targeting anti-Assad insurgent and terrorist groups, is has stepped up patrols and offered to play the role of mediator between parties to the conflict.

Moscow is also capitalizing on its presence in Syria to engage in resource extraction, as oligarch Gennady Timchenko, a close friend of Putin, signed a deal back in March 2018 for his company, Stroytransgaz Logistic, to operate the phosphate mine near Palmyra. Russia, to which the Assad regime gave exclusive oil and gas extraction rights in 2018, has come into conflict with U.S. troops over Syrian oil fields. In short, Russia’s quest for greater military, economic, and political power in Syria will only grow larger as the U.S. military presence decreases.

Iran’s presence in Syria also continues to grow. Tehran has been a strategic ally of Damascus for years. The two countries continue to find common ground over opposition to Israel and regional powers under Sunni leadership. Iran has employed a diverse tactical toolbox in Syria, sending 10,000+ of its own operatives into the country; supporting 130,000+ fighters in Syria, including an estimated 20,000-30,000 foreign Shia fighters; and supply arms and training to Hezbollah to carry out its activities targeting Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and beyond.

Tehran has also spent upwards of $15 billion supporting the Assad regime, and in 2017 alone, it lost an estimated 2,100 troops in the conflict. Iranian power in Syria will likely grow even further with a decreased U.S. presence in the country, allowing Tehran to use hybrid warfare tactics with greater effectiveness to support Assad-aligned groups or nonstate groups such as Hezbollah advancing Iranian interests throughout the region.

The overall geopolitical shifts in Syria remain to be fully seen, as the U.S. has reiterated its presence in the Middle East in light of rising tensions with Iran, sending thousands more troops to Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and elsewhere. Joint Syrian-Russian operations to seize oil fields throughout the country have led to the re-deployment of limited U.S. forces into Syria to protect these strategic resources. Moscow remains committed to bolstering the Assad regime and maintaining sufficient military forces in Syria. Even in the wake of the U.S. airstrike that killed Qasem Soleimani on January 3, Iran has fundamentally retained its usual strategy of proxy warfare in Syria, continuing to carry out attacks on a variety of groups including some backed by the U.S. And Turkey’s role has grown ever-more complex in the recent months and will likely continue to evolve along with events on the ground.

On the Ground

As Turkey moved into northern Syria as part of its “Operation Peace Spring,” the Kurdish-led administration was forced to seek out a deal with the Assad regime. On Oct. 15, a deal to allow Syrian troops to reenter areas previously held by the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) was announced. Under the deal, areas such as Kobane, Manbij, and Ain Issa were now to be occupied by regime forces, which would allow Kurdish troops to pull back to safer areas.

This deal did not come out of left-field, however. In 2018, a similar deal was made to prevent Turkish forces from entering the town of Afrin in northwestern Syria.

A few days after the Syrian-Kurdish agreement in northern Syria, Russia announced its own aforementioned agreement with Turkey. This deal, implemented on Oct. 29, ordered Kurdish forces to pull back to areas deeper in eastern Syria to provide Turkey its intended buffer zone.

In return, Russia, Turkey, and the Assad regime would patrol the buffer zone to make sure the agreement is being upheld by all parties. While the SDF has ostensibly lost much of the territory it gained during the fight against the Islamic State, the deal technically still allows them to retain much of this ground. That said, moves by the Assad regime show a much more dangerous, long-term scenario.

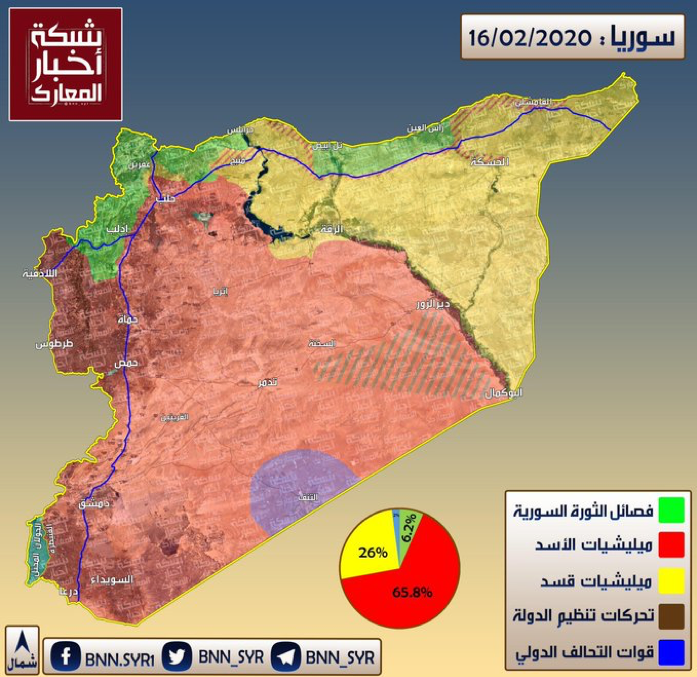

(Map of control as of Feb. 16. Green: Opposition and Turkish troops; Red: Regime; Yellow: SDF; Brown: Islamic State; Blue: US-coalition)

For instance, on Oct. 30, the Syrian regime proposed a new deal with the Kurdish forces. According to the Syrian Arab News Agency, the regime’s official mouthpiece, the Syrian government asked the Kurdish military forces to join the Syrian army, as well as the Kurdish Asayish police to join the Syrian military police. While some observers have postulated that a joint Syrian-Kurdish government could be formed in northeastern Syria, this statement does not bode well for that scenario.

The various deals brokered late last year in northern Syria were believed to act as a win-win situation for the Assad regime. Not only do they get to reclaim some areas lost years ago during the course of the civil war, thereby hampering any chances of a unified Kurdish state in northern Syria; but the deals also allow them to focus their attention more on Idlib province, the last rebel-controlled area in the country. Or so the regime thought.

Since moving back into various areas of northern Syria, regime troops have engaged in various battles with Turkish-backed rebel groups (aptly referred to as the Turkish-Free Syrian Army, or TFSA). TFSA units have attacked regime troops in both Hasakeh and Raqqa governorates.

As the regime continues to move into northern Syria, these clashes have continued. This is especially true as these Turkish-backed forces continue to conduct attacks in areas where Syrian troops have deployed. For instance, in late October, the sides clashed near Tel Tamer.

These units have also fought with the SDF, as in November, heavy rounds of fighting were reported near Ain Issa. Later that month, the TFSA units again tried to attack near Ain Issa, prompting another round of clashes with the SDF.

In Idlib, many of the TFSA units have redeployed to various areas in the province to help fend of the current regime advance. Shifting their attention from the SDF, these forces have provided force multipliers for other rebels, the jihadist conglomerate Hay’at Tahrir al Sham, and other jihadist groups in the province. Armed with new Turkish weaponry, the Turkish-backed fighters have even recently downed a regime helicopter with anti-air missiles.

Though uniformed Turkish troops have also engaged the Assad regime and its allies. Indeed, on Oct. 30, Syrian and Turkish troops clashed near the town of Ras al Ayn near the Syrian-Turkish border. While on Nov. 9, another round of clashes between Turkish and Syrian government troops occurred near Ras al Ayn. Further clashes risk reigniting the flames of war in northern Syria, thereby exacerbating the civil war even further.

As the regime and its allies move further into Idlib, where Turkey maintains several outposts, it has lost more soldiers to regime airstrikes. For instance, on Feb. 3, at least 8 Turkish troops were after Assad’s soldiers shelled their positions. Five more Turkish troops were killed by the regime a week later. Turkish airstrikes were reportedly launched in retaliation.

On Feb. 20, two other Turkish troops were killed after further regime or Russian airstrikes. It is possible that these soldiers died as the result of Russian airstrikes, as video emerged showing alleged Turkish special forces firing an anti-air missile at a Russian jet. Russian airstrikes against Turkish troops have also been reported.

While the Russian jet was not downed, it stands to reason that this scenario could play out if Turkish troops continue to launch anti-air missiles. Though it is unclear what the repercussions could be as Turkey has previously downed a Russian jet. However, this does represent a chance for further escalation among the foreign powers inside Syria.

Conclusion

As of this month, there are around 500 U.S. troops in Syria, and their primary mission is to protect oil fields. Despite this continued, albeit small troop presence, the initial decision for troop withdrawal in October has allowed Turkey to invade northern Syria against the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces, Syria to regain several lost locales, and Russia to step in and play an even greater role in the country. The changing geopolitical landscape in Syria will continue to have serious geopolitical implications not only for the region, but US interests as a whole.

Photo credit: The New York Times, Associated Press