Horror fans are probably already aware that Guillermo del Toro has released a new series, an anthology of shorts available on Netflix titled Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities. As the acclaimed horror director introduces each episode, he draws an object from the eponymous cabinet, representative of the story we are about to be told. Here the show is clearly forging a connection to the cabinets of curiosities, or wunderkammers, that were found in the homes of those wealthy and well-connected enough to assemble collections of strange, foreign, and valuable art and objects. Del Toro’s horror series ties in with a specific aspect of these collections, this being the idea of the monstrous. What better way to show your reach and wealth as a patron than to put on display creatures and objects which are typically outside of our control, or break with our understanding of the natural order?

We have long been fascinated with the inhabitants of the periphery of our understanding: creatures and ideas that lie between the fantastical and the real. Just plausible enough to be imagined, but not necessarily so common or true that they are a part of everyday life. This has been explored at length in art, and many examples reveal just how artists attempted to materialize the monstrous.

The 2016 horror video game Layers of Fear, centered around a painter returning home to complete his final masterpiece, explores this topic. The player must explore the kaleidoscopic rooms and corridors of his house, completing puzzles in order to create an ever more disturbing painting. Art plays a central role in creating an atmosphere of psychological horror, with nearly every wall filled with real art supplementing the works created in-universe by the player-controlled artist. Among these, we can see classic examples of horror in art, such as Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare, Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Beheading Holofernes, and several works from Francisco Goya’s black period. All of these works channel some of our deepest fears and discomforts. Artemisia Gentileschi’s famous painting is a dynamic composition leading the eye towards the sword slicing through Holofernes’s neck, while Fuseli’s embodies the form of a nightmare through an uncanny horse and goblin. Goya instead turns to images of witches and the demonic, as well as disturbing depictions of violence and death.

Right: Francisco Goya. Saturn Devouring His Son, c. 1819-23. Mixed media mural transferred to canvas, 143.5 x 81.4 cm. Madrid, Museo del Prado.

Among all of these, however, is an unusual painting. It is a half-length portrait, depicting a little girl holding a piece of paper. She is gazing calmly at the viewer, dressed in rich, sixteenth-century clothes. Her mouth is turned slightly upwards in a subtle smile, and her chubby hands and cheeks reveal her tender age. Why, then, is this young girl placed alongside so many disturbing images in a game where art is used to amplify the horror atmosphere of this haunted home?

Her name is Antonietta Gonzales, and, like her father and most of her siblings, she had a condition called hypertrichosis. This condition is ultimately the reason she is included in this collection. Hypertrichosis causes abnormal growth of hair, covering the individual’s body almost entirely. The paper she holds provides identifying information on her and her family:

“Don Pietro, a wild man discovered in the Canary Islands, was conveyed to his most serene highness Henry the king of France, and from there came to his excellency the Duke of Parma. From whom [came] I, Antonietta, and now I can be found nearby at the court of the Lady Isabella Pallavicina, the honorable marchesa of Soragna.”

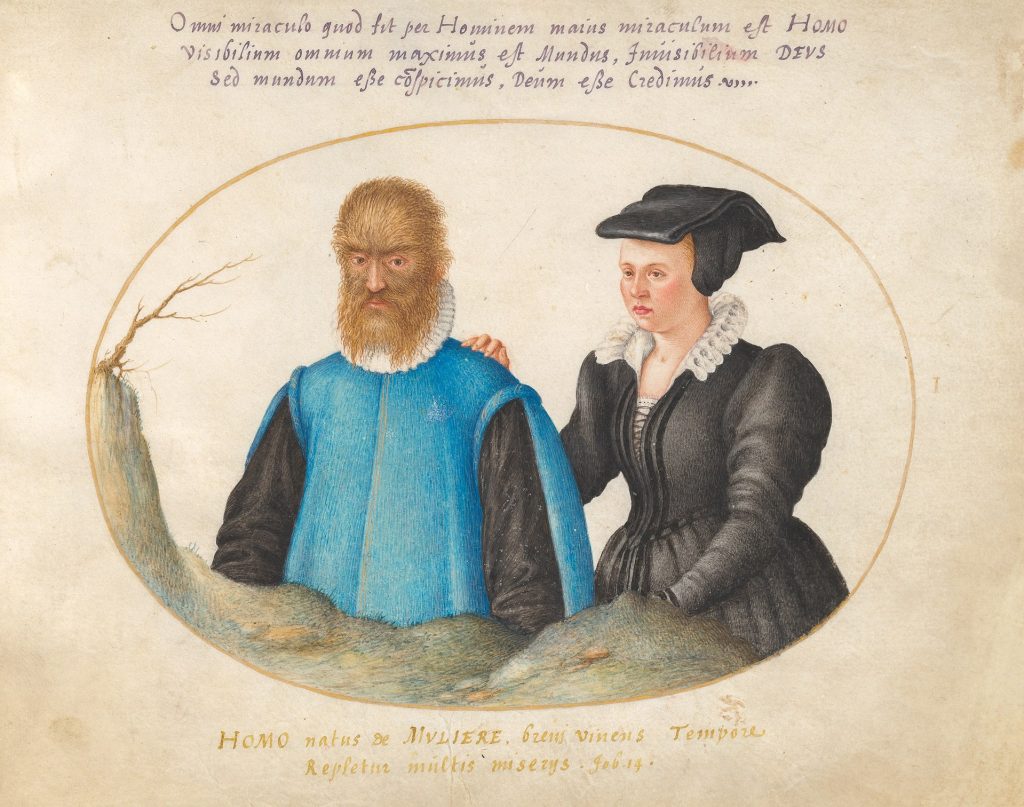

An illustration from the late 16th century shows Antonietta’s parents, Pedro Gonzalez and Catherine. Born in Tenerife in the Canary Islands in 1537, Pedro was brought to France, where he was educated by the court in an experiment to make a cultured man out of what the naturalist Ulisse Aldovrandi called “the man of the woods.” Pedro and his children, four of which had the same condition as him, were treated as less than human, viewed in a similar manner as the objects and specimens that filled the wunderkammers and menageries that the royals and upper class of Europe retained.

Today, a similar attitude can be seen in the fictional gallery created in Layers of Fear. A smaller version of the portrait can be seen throughout the house, but it is placed front and center in the study. Upon entering, the player sees the portrait hung in a prominent, central position in the wall directly in front of them. Several factors impact the player’s reaction and understanding of this image. First, it is already known that we are playing a horror game, and thus any visuals are considered in such a light. We have already encountered several disturbing works before entering this room, and as such are even further prepared to perceive any further work of art in a similar way.

Most players’ reactions reveal the impact this has. Nearly every single player acknowledges this painting with surprise or disgust, especially when it is highlighted in the study. Markiplier remarks “Oh god, oh god, oh it’s so… oh my god. That is so weird. Oh, what’s wrong with your face?” and Jacksepticeye exclaims “Like what the f*** is this? A beard baby!?” Several others compare Antonietta to a human-animal hybrid, a way of thinking that is strikingly similar to the dehumanizing rhetoric peddled by Antonietta’s contemporaries. During a GTLive stream of Layers of Fear, Matt says “Ugh… I am not a fan of that painting. […] Hey owl man. It’s actually a wolf, right? […] Wolf baby! Beware the wolf baby.” Another live stream, this time from DashieGames, similarly adds “What the hell is that? […] That’s like wolf-man baby.” It’s remarkable to see how the worldviews that shaped Antonietta’s life in the 16th century are repeated in the 21st.

The depiction of the monstrous—be it through allegories of our deepest fears, violence, or, in Antonietta’s case, people who look different than the established norm—reveal a steady line between the earliest museums (in the form of cabinets of curiosities) and our imaginations today. This brings us to wonder about the role that museums (whether real or through imagined collections, like that of Layers of Fear) play in amplifying these fears and prejudices. Are we cementing the fears and prejudices that dehumanize those with physical or mental illnesses and deformities?

Sources:

Aldovrandi, Ulisse. Monstrum historia. Bologna: Typic Nicolai Tebaldini, 1632; repr. Paris: Belles lettres, 2002.

Dashiegames. “I WAS TOO SCARED TO PLAY THIS ALONE! HELP ME!! [LAYERS OF FEAR] [#01].” YouTube video, 2:18:06, June 18th, 2021. (link)

GTLive. “The Portrait of TERROR | Layers of FEAR! (Part 1 of 2).” YouTube video, 1:45:01, November 11, 2016. (link)

Jacksepticeye. “ALONE AND AFRAID | Layers of Fear – Part 1.” YouTube video, 30:02, October 28, 2016. (link)

Markiplier. “OODLES of SPOOPLES | Layers of Fear #1.” YouTube video, 21:25, October 31, 2015. (link)

Wiesner-Hanks, Merry. The Marvelous Hairy Girls. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009.

Article by Francesca Bisi

MA Candidate in Art History and Museum Studies, Tufts University