At thirteen, I picked up David McCullough’s hefty volume on John Adams and the course of my life changed. A special fascination with early American and United States history was formed in my heart that would, eventually, inspire my decision to pursue History and Museum Studies at Tufts.

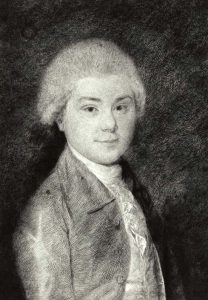

John Quincy Adams at 16. He was a boy genius who had already served the new American nation as secretary to the foreign minister to Russia.

As I read, it wasn’t the character of John Adams who most piqued my interest, but those of his four children, who, more keenly than anyone, felt the pains and dealt with the lifelong repercussions of their father’s frequent absences in the name of serving his country. The oldest son, John Quincy Adams — a brilliant, creative, moody, dutiful aspiring poet whose head was often in the clouds — became my special interest.

When I was eighteen, a longstanding dream came true when I visited the three historic homes at the Adams National Historical Park. I walked through the halls and across the grounds where young John Adams, then his children, then their children studied, worked, and played. I was enchanted by the beautiful stone library on the Old House property; an elderly John Quincy Adams made his son promise he would build the structure to protect his beloved collection of 8,000 books from fires. I listened to our guide’s exciting rendering of the story and took in the scent of all those carefully preserved old pages.

Then, on Monday, July 12th, 2021, I was able to live another dream. At the United First Parish Church in Quincy, Massachusetts, where both Adams presidents worshipped, I attended a wreath-laying ceremony for John Quincy Adams’s birthday. If such longevity was possible for human beings, the eleventh of July would have seen him turn 254.

Such speakers as the Mayor of Quincy, the President of the Quincy City Council, the Minister of the United First Parish Church, and of course representatives from the Adams National Historical Park and the Quincy Historical Society took the podium to speak of Adams’s courage, and the strong principles that alienated him from political enemies and allies alike, for which in death he has earned substantial respect. They spoke of the courage we have had to employ as a community, as a nation, as human beings this past year. They spoke of the importance of John Quincy Adams’s example in such times as these.

After the ceremony, I went with a knowledgable, passionate church guide and a curious, kindly schoolteacher into the crypt beneath the United First Parish Church, where John Quincy Adams, his wife, and his parents are all buried. It was a bit of a heart-stopping moment for me. I’d longed to see this for much of my life.

JQA’s tomb with the presidential birthday wreath, at the United First Parish Church, a historic site in Quincy. 12 July 2021.

It was cold and stark, except for the American flags resting on the tombs of both men, and the beautiful presidential wreath adorning John Quincy’s for this special day. I placed my hands over his name and reflected.

Like all of us, he was a complex person. He is well-known now for his battle in the House of Representatives for the abolition of slavery in his twilight years, and his successful defense of the Amistad Africans before the Supreme Court at the age of 73. But it had taken him this long to ever speak up for the rights of Black individuals, in a nation he had served almost non-stop since before his fifteenth birthday, having held virtually every political office possible. I thought about the enslaved peoples in this nation as I stood beneath the church.

He came to care about the rights of Native peoples in the United States, but only after doing irreparable damage to the lives of many by approving of and fueling dispossession of lands in his earlier career. I thought about them as I stood beneath the church.

He was not a good father. Rather than break the cycle by recognizing the harsh ways his parents pushed him toward glory, he treated his own sons with even more cruelty. Two out of three of them died tragically, and young. I thought about them, and all the other Adamses who did not meet their family’s standard of greatness and, so, are not buried in this crypt (or remembered by history), as I stood beneath the church.

I walked afterward to Penn’s Hill, the spot in Quincy where John Quincy Adams, a month shy of his eighth birthday, walked with his mother on the night of June 17th, 1775, and watched Charlestown burn while the Battle of Bunker Hill raged. He was haunted for the rest of his long life by the flames and the sound of the guns. Every year, Boston held a celebration to commemorate the courage of the militiamen who fought at Bunker Hill; he never attended a single one.

I lingered there. You can’t see Boston anymore; Penn’s Hill is surrounded by neighborhoods now, and the fifteen-minute walk there from the little farmhouse where Abigail Adams raised her children is lined with homes and businesses. I thought about courage and principle; I thought about those whom history celebrates and those whom it forgets; I thought about the seven-year-old who held his mother’s hand while he watched the world fall apart across the shoreline — unaware that, two and a half centuries later, people would be tromping through his childhood home, marveling at his stone library, placing their hands on his tomb to think about those he helped, those he ignored, those he hurt.

The farmhouse where John and Abigail Adams raised their brilliant son “Johnny,” his older sister “Nabby,” and his younger brothers “Charley” and “Tommy.” Today, it is a historic house museum.

I thought about the power of history, the power of museums, the power of place and story, to connect us to all those who have come before, so that we can learn from their examples and swear to do better.

The grounds at the Adams National Historical Park are open, and the museums are preparing for a phased reopening after the pandemic. Click here for more information.

The United First Parish Church, also known as the “Church of the Presidents,” is open again for tours of the sanctuary and the Adams crypt. Click here for more information.