Next summer, the United States will mark a somber anniversary. In August of 1619, the first recorded group of African people destined for sale in the colonies arrived in Jamestown, Virginia. Although, as Michael Guasco argues at Smithsonian.com, the date is not as important as many make it out to be, for race-based slavery was already well underway in other parts of the Americas, this is a date in US history that will likely be met with a fair amount of commemoration. As with other anniversaries marking the advance of European conquest and settler colonialism in the Americas, this event is an opportunity for museums and educational institutions to present content and programming that grapples with the complicated and complicit legacies of racism, colonialism, conquest, violence, and slavery in US History.

In looking at the 2019 Commemoration page for the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, doing justice to this difficult history does not appear to be at the center of their plans. This anniversary is one of four being celebrated this year, along with the arrival of English women, the first meeting of a representational assembly in the European Americas, and the first official Thanksgiving. In general, the events planned seem to be focused on “the entrepreneurial and innovative spirit of the Virginia Colony”, that seeks to “build awareness of Virginia’s role in the creation of the United States and reinforce Virginia’s position as a global leader in education, tourism and economic development.” In other words, these events are presented as an opportunity for economic development and tourism promotion, rather than for reflection or reparative work.

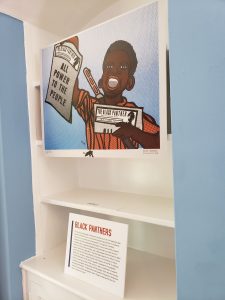

This is an excellent moment to reflect on the idea put forward by LaTanya Autry and Mike Murawski that “Museums are not neutral”. Every exhibit, program, marketing material, and tour given at a museum is crafted by people with unique collections of knowledge, perspectives, and goals. They bring their own life experiences to how they view the world and a hierarchy to what they deem important. Though many might aim for neutral presentations in their work, the fact of the matter is that there is no neutral, there is only the illusion of neutrality, which usually manifests in “default” presentations: content that focuses on white Europeans, on men, on the cis-gendered and heterosexual, on the non-disabled, on the wealthy. In a history museum, the archive, too, is biased in favor of these individuals, making it appear as if all of humankind’s history has only been for these humans.

What, then, should the goals of a commemoration of a terrible anniversary like the first arrival of enslaved Africans endeavor to encompass? Here are a few thoughts, and by no means is this list exhaustive. We welcome your additions in the comments.

- Placing the US and its adoption of slavery in a larger Atlantic context that acknowledges the economic interdependence of the British colonies and situates their actions amid European empire building of the era.

- Acknowledges the transition to race-based slavery and the long lasting ramifications of that change.

- Remembers that though the crime committed was vast and difficult to process, for each human who endured the violence and violation of bodily autonomy, the trauma was real, specific, and inescapable.

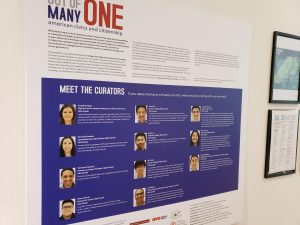

Above all, this is a good moment for museums to take a hard look internally to assess how the legacy of slavery is manifesting within their own institutions. Who are the curators? Are there people of color in positions of power in the organization? Who has input into telling the story of this group of Africans? Does the story told center the experiences and legacies of those most affected, or is the story used to strengthen a dominant group? These are only a few jumping off points for exploring this and similar events as we navigate a number of coming quadricentennials with complex narratives.