This week I will be exploring the Iziko South African Museum in Cape Town, South Africa and the Museum’s attempt at decolonizing a controversial and culturally damaging exhibit space in the post-apartheid period.

The Iziko South African Museum (SAM) is one of an amalgamation of eleven national museums in the Cape Town area. The cluster of museums were founded in 1998 with legislation to break down the power structures in the existing museums. The Izizko Museums of South Africa include the South African National Gallery, the Bo-Kaap Museum, and even the interpretive areas of a local winery. Iziko means hearth in isiXhosa, one of the eleven national languages in South Africa. In the isiXhosa tradition the hearth is the social center of a home and is the space associated with warmth, kinship, and shared stories. In naming the national heritage institution after the hearth they are declaring them “centers of cultural interactions where knowledge is shared, stories told, and experiences enjoyed.”

Although SAM is part of the Iziko Museums, it has a longer history as the first museum in South Africa founded in 1825. The museum focused on natural history. Like many 19th century natural history museums, SAM included material culture from local indigenous groups while reserving cultural history museums for the display of settler culture. The practice of displaying cultural”others” next to animals in Natural History museums has long been opposed. This practice was exemplified with “Bushman” Diorama which had been on display in the museum since 1960. The display was controversial not just for its racial stereotyping and inaccurate representation of Khoe-San culture, but for the use of body casts that were taken from 1907 and 1924 which had been painful and humiliating for the participants.

The diorama was closed in 2001 and was replaced with |Qe: The Power of Rock Art. At the entrance to the exhibit space, SAM acknowledges the harmful history of the space with a message Jatti Bredekamp, Iziko CEO.

|Qe- The Power of Rock Art is a milestone in the history of this Museum, the oldest on the African sub-continent. For almost a century the South African Museum housed some of the most significant examples of rock art produced by San artists, however it was better known for displays of plaster body casts that emphasized the physical features of san people rather that their history and culture.

The Tragic history of dispossession, brutality, and cultural loss that befell the San people at the hands of the colonial settlers was overlooked in favour of idealized displays that reinforced stereotypes. In 2001 the so-called Bushmen Diorama was closed to allow for a process of consultation with descendant communities. In planning the rock art exhibition we initiated a conversation with Khoe-San communities regarding the ways Iziko presents their cultural heritage. This has enriched the exhibition immensely and the dialogue will continue.

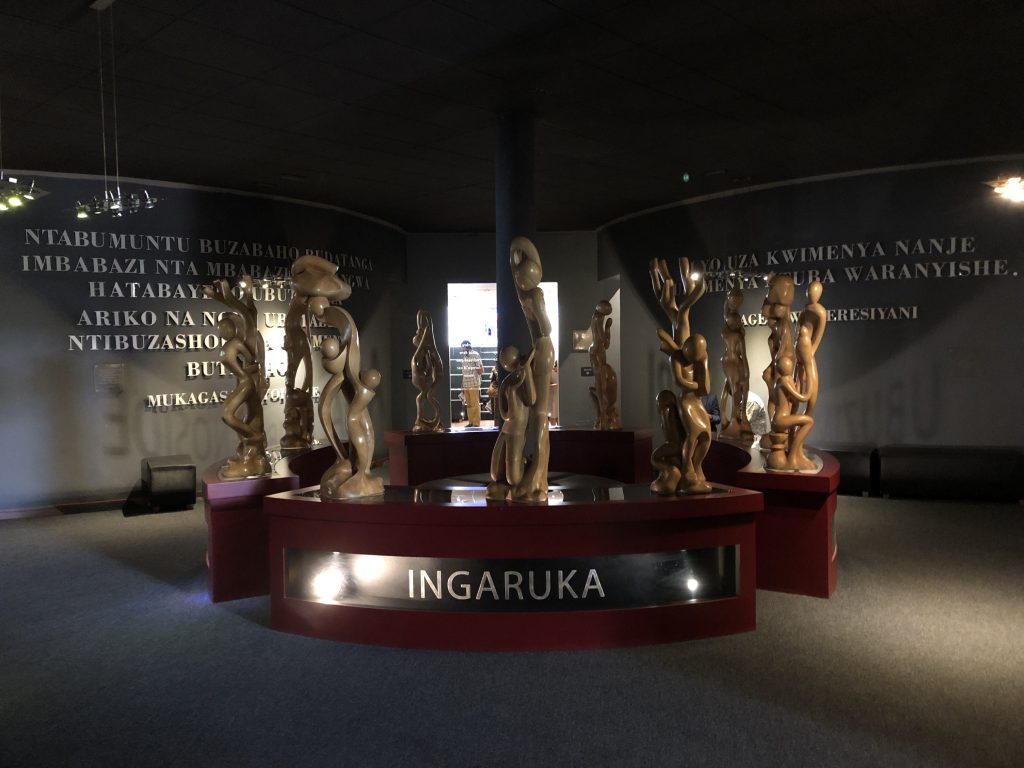

The exhibit opened for permanent display in 2003 with the aim of acknowledging the spiritual power rock art had for the indigenous people of southern Africa. The exhibit title was developed with consultation of modern day speakers of N/u, a language related to /Xam, the now extinct language of the souther San. The use of the word “|Qe” is meant to convey the pervasive sense of power of the art.

When I visited in January of 2019, the exhibit had been updated slightly to reflect the recent finds from the Blombos Cave in South Africa. These finds have been used to show the earliest signs of art in Anatomically Modern Humans, previously designated to European rock art, with the discovery of carved ochre and what may have been the production of ochre pigments dating back 70,000 years. The exhibit itself was laid out over two rooms telling, in my opinion, three connecting stories: 1) The history of rock art in South Africa and the rest of the world 2) The production of rock art by San people prehistorically through modern day and its significance culturally and spiritually, and 3) The work of Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd in the 1870’s to record the oral literature of the /Xam.

While the third story gave context to the interpretation of the rock art using the now extinct /Xam language, I felt its inclusion did a disservice to the exhibits intent of decolonizing the space. The Bleek and Lloyd story line exposed the “White Saviorism” the museum was still representing. For a more in depth critique of the exhibit and its disingenuous attempts at representation I recommend reading Remaking /Xam Narratives in Post-Apartheid South Africa by Hendricks Mona D. Additionally, although the exhibit boasts its consultation with San communities, it is still displaying a historically “othered” group in a natural history museum. This point becomes complicated as often human material culture of the Pleistocene is relegated to Natural History Museums. However, the strength of this exhibit is in how it connects the early, prehistoric rock art to the modern-day San, as the continuation of a rich culture.

It is through the connection of the first and second storyline that the exhibit was most successful. When colonizers first found rock art in southern Africa they believed the art was too complex for the “primitive” San. The Khoe-San were racialized as being the lowest on the evolutionary time-scale. The connection between modern San rock art and prehistoric rock art turns that narrative around by showing the depth of San culture and tracing them back to the earliest Anatomically Modern Humans in South Africa. Furthermore, through the interpretation of recent rock art by descendants of /Xam speakers we can better understand the why? behind the rock art of South Africa.

While I think the Iziko South African Museum has much work to do to decolonize its practices, |Qe: The Power of Rock Art, is an interesting exhibit in its telling of South African rock art. My hope is that the museum will continue to hold conversations with the Khoe-San communities and to break down the power structures upheld through colonialism and apartheid.

Further reading:

Remaking /Xam Narratives in Post-Apartheid South Africa

Limitations of Labels: Interpreting Rock Art at the South African Museum

The Politics and Poetics of the Bushman Diorama at the South African Museum