At Tufts University, the course on Classical Historians (Classics 141 — details in the departmental course booklet) will focus on Classical Arabic sources composed in, and about, pre-colonial West Africa. While we will consider Arabic sources produced outside of West Africa and accounts of European travelers, we will focus primarily on two different historical sources from West Africa istself: the Tārīkh al-Sūdān and (what has traditionally been called) Tārīkh al-Fattāsh. Our goal is not just to learn about the Mali and Songhai empires but to use what we learn to create openly licensed, digital sources of various kinds that will help others explore a major historical period that has attracted far too attention in the teaching and research.

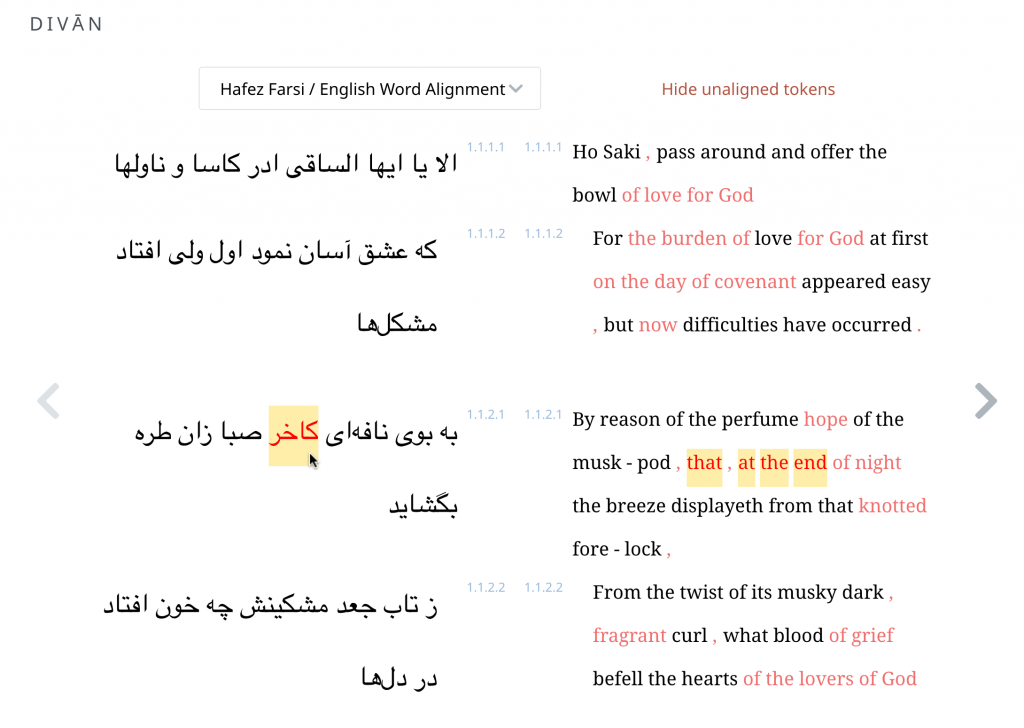

Students will have an opportunity to explore emerging, digitally enabled methods by which global audiences can begin exploring the human record. In particular, we will exploit techniques by which we can begin to make the Arabic source text itself accessible to a general audience. We will begin publishing sections of these sources in the new version of the Perseus Digital Library that we are developing with support from the NEH. The development site for this is Beyond Translation and will be augmented between now and the fall semester.

Figure 1:Conclusion of an unpublished historical source in Arabic from Mali, preserved by Yaro family collection and hosted by the British Library – one of more than 2,000 West African manuscripts that the British Library has made available.

The course itself will meet during Tufts’ fall semester Monday evenings from 6:00-8:30. Space allowing, we hope to see students from other institutions participate, whether by direct cross-registration or by getting credit through a directed study authorized by a faculty member at their own institution.

We will also offer a weekly reading group for those who wish to go over sections of the Arabic. This will can be taken as an optional addition to the Monday class or as a separate class. The Arabic reading group would be 1 credit (vs. 3 for the Monday class). Any students taking both would receive 4 credits.

During the summer, I will also be working on the digital edition of these two histories and of other sources. If others are interested learning more and in possibly contributing, they should contact me. There are a number of ways to contribute that match a range of skillsets. The basic requirement would be an ability to read English carefully but there are also clearly opportunities for those with knowledge of French, of various aspects of Computer and Data Science, and of Classical Arabic.

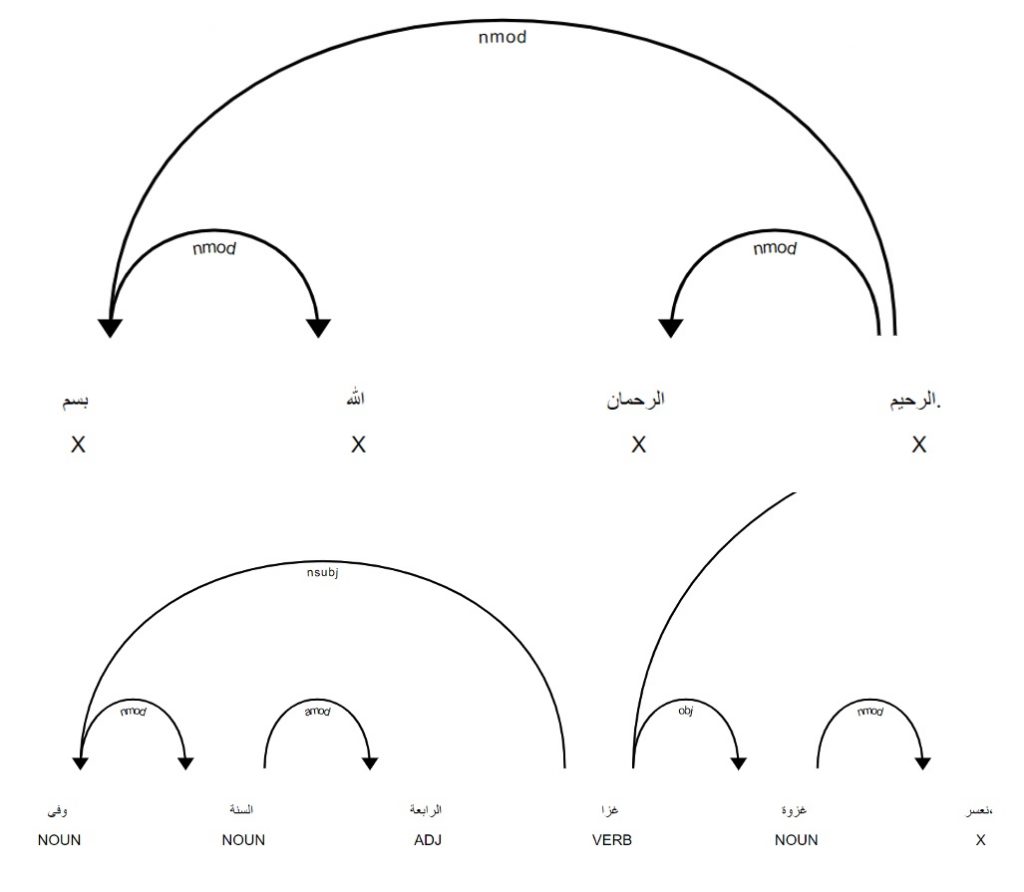

I am hoping this summer to resuscitate my own Arabic and to see how far that helps me with the language of these Islamic scholars from Timbuktu. I will be using tools such as the suite of Arabic natural language processing tools developed by the CAMeL Lab at New York University Abu Dhabi to extend my (not very advanced) knowledge of Arabic. The goals are to create exhaustive annotations, included translations aligned at the word and phrase levels, for (1) a small but extensible set of passages and (2) sets of sentences that allow readers to trace the meaning of Arabic words which cannot properly be translated.

The larger goal of this class and the larger project that it represents is to create openly licensed digital materials that are not only of immediate use but that also can be modified and, wherever possible, reused under a Creative Commons CC-BY license. Such a license is not suitable for publications that seek to represent a particular scholarly voice at a particular time. We are, however, managing the sources in Github and so each particular contribution is recorded in the versioning history. We are supporting a collaborative model of authorship that may be familiar to readers from Wikipedia. That said, individuals will be able to use the Github versioning history to document what they have done and to create hybrid publications that contain their own accounts of what they did and what critical decisions they needed to take.

The Tārīkh al-Sūdān and the Tārīkh al-Fattāsh

The fall course will focus primarily on two histories — tarikh, pl. tewarikh — composed by Islamic scholars in West Africa.

(1) The Tārīkh al-Sūdān (TS) by al-Sa’di (1594-1655+ CE) focuses on the history of the Songhay Empire from the mid-fifteenth century until 1591 and then the Moroccan invasions and subsequent administration down to 1655. Houdas (Sa’dī 1900 and 1900a) published the Arabic text and a French translation. In 1999, John Hunwick published a scholarly translation with notes that covered the 28 of 35 chapters most relevant to Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire.

(2) Thirteen years later, Delafosse (1913 and 1913a) published the Arabic text and a French translation for a far more challenging source that has been known as the Tārīkh al-Fattāsh (TF), the “Chronicle of the Researcher,” an account of the Songhay Empire through 1599 and thus includes the early years of the Moroccan occupation. Almost a century later, Wise and Taleb (2011) published an English translation of the Tārīkh al-fattāsh based on Delafosse’s French translation and the Arabic text. Tārīkh al-fattāsh is a novel chronicle written in the 19th century, and not the effort of three generations of scholars who worked on it starting from the early 16th century and eventually interpolated in the 19th century, as previously advanced by most scholars. This 19th century TF was composed by a substantial rework of a 17th century anonymous work. With support from the NEH Translation Program, Mauro Nobili and Ali Diakite are publishing a new edition of this work that contains an English translation, the Arabic text and clear indications of how the 16th and 19th century texts relate to each other.

We will, however, also consider other sources. We have a reasonably accurate transcription for the Arabic of Ibn Battuta’s description of West Africa and an accompanying French translation, long in the public domain. We can use DeepL or Google Translate to create a quick first English version and then edit this as we align it to the Arabic original.

Where the project stands.

Work on this project begin in summer 2021, when Ayah Aboelela (UMass Boston CS ’21) led preliminary work. We found not only PDF versions of the public domain Arabic/French editions of the TS and TF but also text automatically generated by Optical Character Recognition.

The French OCR-generated text was good enough as a base for further work. We applied DeepL and Google Translate to convert the French into English. The results were surprisingly good: we did find ourselves making occasional changes to the English but such correction did not materially add to the overall work of adding base TEI XML tags, marking footnote markers in the text and footnotes on the bottom of the page, adding occasional Arabic words in the notes, and adding Arabic numbers in the translation that pointed to the corresponding pages in the Arabic edition. Readers can examine a sample of such work, chapters 21-22 of the TS on Github.

The Arabic text was more problematic and, in two different OCR-workflows, had a character error rate of c. 5%. The text is still sufficiently accurate to support a range of text mining (such as topic modeling and text reuse detection). It is also good enough as a starting text if the goal is to add extensive annotation to relatively short passages and to create an initial reader. Ayah produced initial versions of curated passages where she took the time to correct errors in the OCR-generated text.

A few thousand words of carefully edited Arabic with aligned translation and annotation would be a useful start and allow readers at an intermediate level to familiarize themselves with the style and content of these sources before moving to passages without curated annotations and translations.

Ayah published exploratory work using natural language processing tools for Arabic available from Spacy and CAMel on Github. She tested services for morphological analysis and disambiguation and dependency parsing for the Arabic.

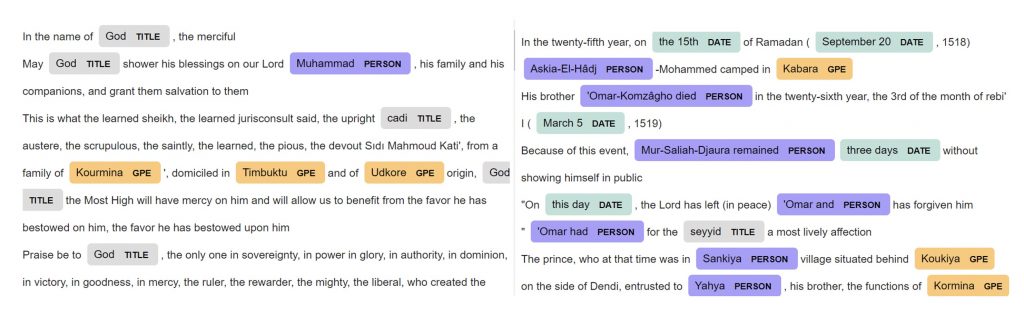

For named entity recognition (NER) (determining whether names are people, places or groups), we decided to apply tools from Spacy to English generated from the French with machine translation. A relatively modest amount of training improved the accuracy of NER from 60% to 82%.

Not only do these two histories constantly refer to places with which most readers in the US are probably not familiar, but there are many personal names, often complex in form, and rarely familiar.` Identifying these names and creating links between related characters, and linking this information directly to the source text will, we hope, make it easier for readers to see who is who and to identify characters on whom they should focus their attention.

Figure 5 illustrates social networks derived from primary sources about Roman history. We use simple collocation to posit connections. Our hope is to include more complex information about relationships (son-of, occupation, etc.). Zach Sowerby was working with a much larger text corpus than the two histories and his relatively rapid prototyping already reveals basic patterns of who is important and which characters are connected. We can get useful information starting with this fairly rapid work.

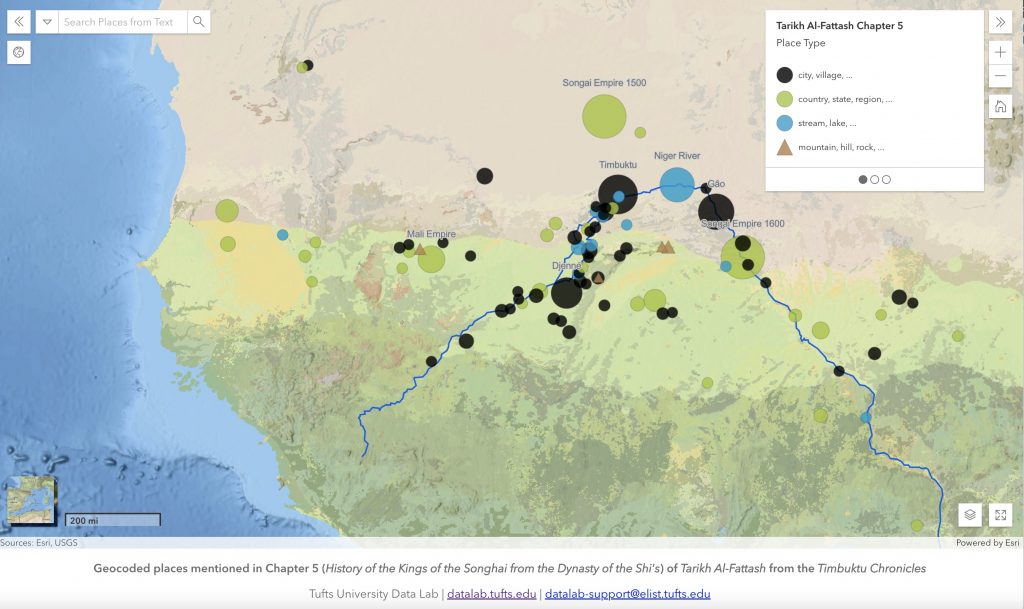

In fall 2021, I taught the first iteration of this class. We spent much of our time reading Michael Gomez’s 2018 book African Dominion, now the standard English account of early and medieval West Africa and then examining the accounts in the two histories on which Gomez bases much of his work (and which he carefully cites). The map in Figure 2 (above) was produced for this class by members of the Tufts Data Lab as a model for additional student work. I will adding results from student projects in this class during the summer.

Let’s see what we can do in the summer and then in the fall!

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible by the Beyond Translation Project, funded by NEH HAA-266462-19 and by support from the Data Intensive Studies Center at Tufts University, and by collaboration with Eldarion.