Gregory Crane1, Alison Babeu1, Farnoosh Shamsian2, James Tauber3, Jacob Wegner3

1 – Tufts University; 2 – Leipzig University; 3 – Eldarion.com

[Preprint of the abstract for Digital Humanities 2020: Responding to Asian Diversity – https://dh2022.adho.org/]

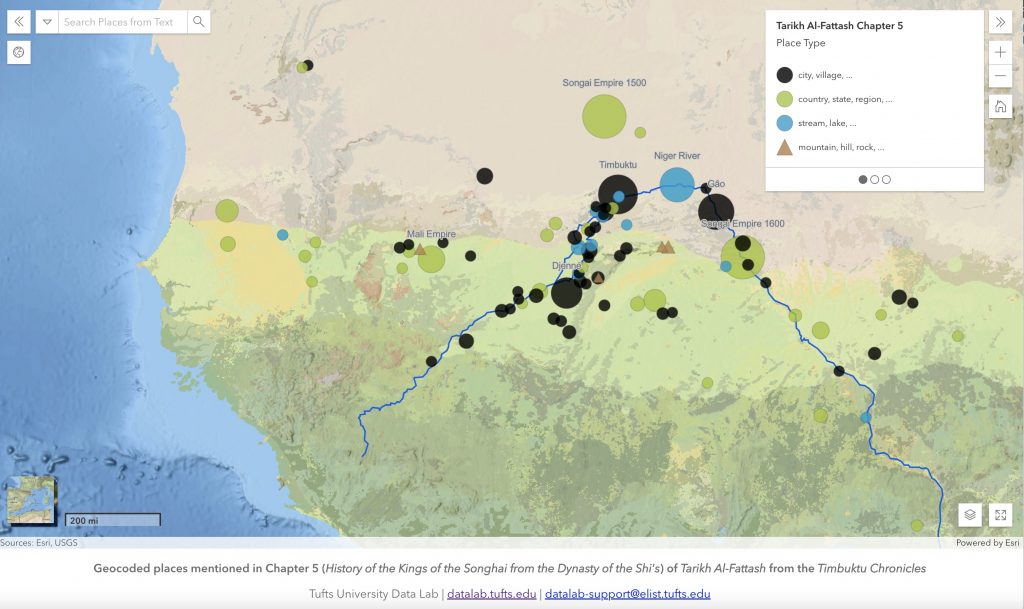

Our work explores the hypothesis that a new mode of reading is taking shape, one in which dense, machine actionable annotations allow readers to work directly and effectively with sources in languages that they do not know – a new middle space between reliance on translation and mastery of the source text (Crane et al. 2019, Crane 2019). This hypothesis has substantial potential importance for our ability to use source texts to explore cultural diversity in general and the diversity of Asian cultures in particular. Our particular work focuses on two challenges for a traditionally Eurocentric subject, Classics (or Classical Studies), which is still used to describe the study of Greco-Roman culture. On the one hand, university students without training in Greek and Latin in secondary school have difficulty mastering the languages and learning about the subject. In spring 2021, the Princeton Classics Department provoked controversy when it made it possible for majors to study Greco-Roman antiquity without learning any Greek or Latin — too few students, especially students of color, had access to Latin, much less Greek, before college (Wood 2021). At the same time, Classics and Classical Studies are far too narrow – we must include other classical languages – Sanskrit, Classical Chinese, Classical Arabic, etc. – if we are to continue using these terms. We report on work that addresses both challenges.

In order to explore this broad topic, we chose to focus on two complementary corpora in two Classical languages: the Homeric epics in Ancient Greek and the Shahnameh in early-modern Persian (Firdawsī 1430, 1988). The goal is both to support Persian speakers who wish to work directly with Homeric Epic and English speakers who wish to engage directly with the Shahnameh. In the case of Persian culture, the links with Greco-Roman culture are deep, the information in Greek sources about ancient Persian history is extensive, and the influence of Greek philosophy, medicine and science are extensive. At the same time, few institutions in Europe and North America, for example, teach modern Persian, much less the early modern Persian of the Shahnameh. We hope to increase the role that the Persian epic, in Persian as well as in translation, plays beyond the Persian speaking world.

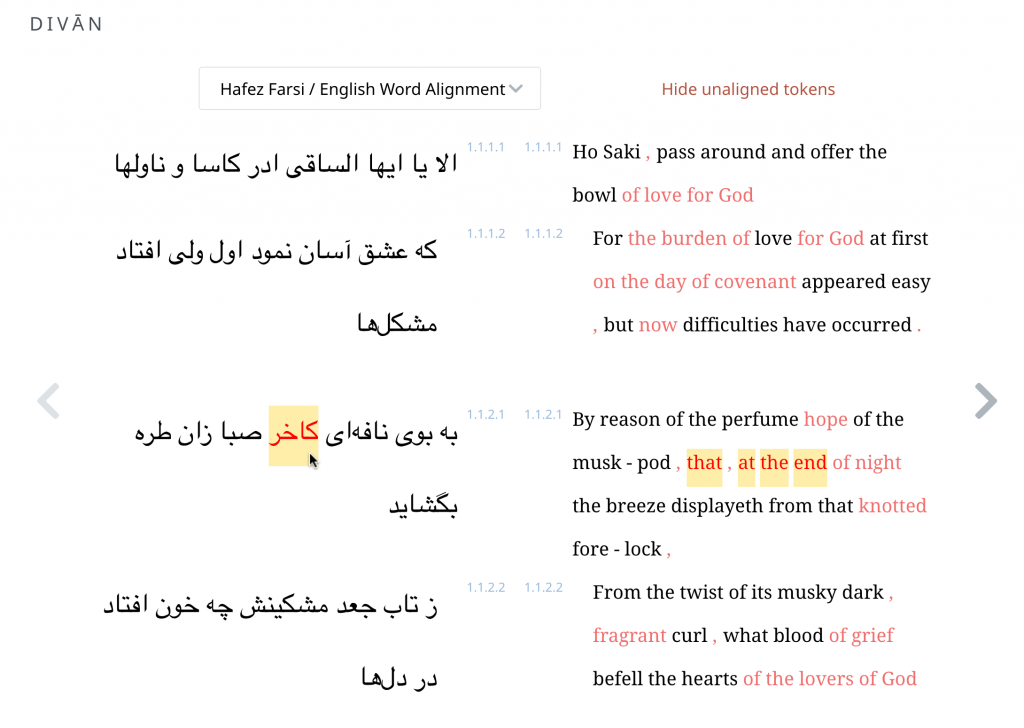

The use of dense linguistic annotation to make sources accessible to a broader audience is, of course, hardly new. In his late seventeenth-century description of Ottoman Turkish, Arabic, and Persian, for example, Franciszek Meniński (1680) introduced Persian poetry to a European audience by transliterating a passage from a poem by Hafez, providing a word-by-word translation, and providing detailed explanations of the metrical, morphological, and syntactic function of each word. Contemporary linguists depend upon exhaustively annotated text to work across sources from the thousands of languages, ancient as well as modern, in the human record (Werning 2009).

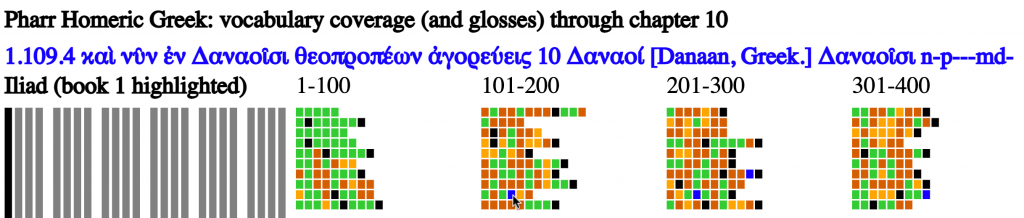

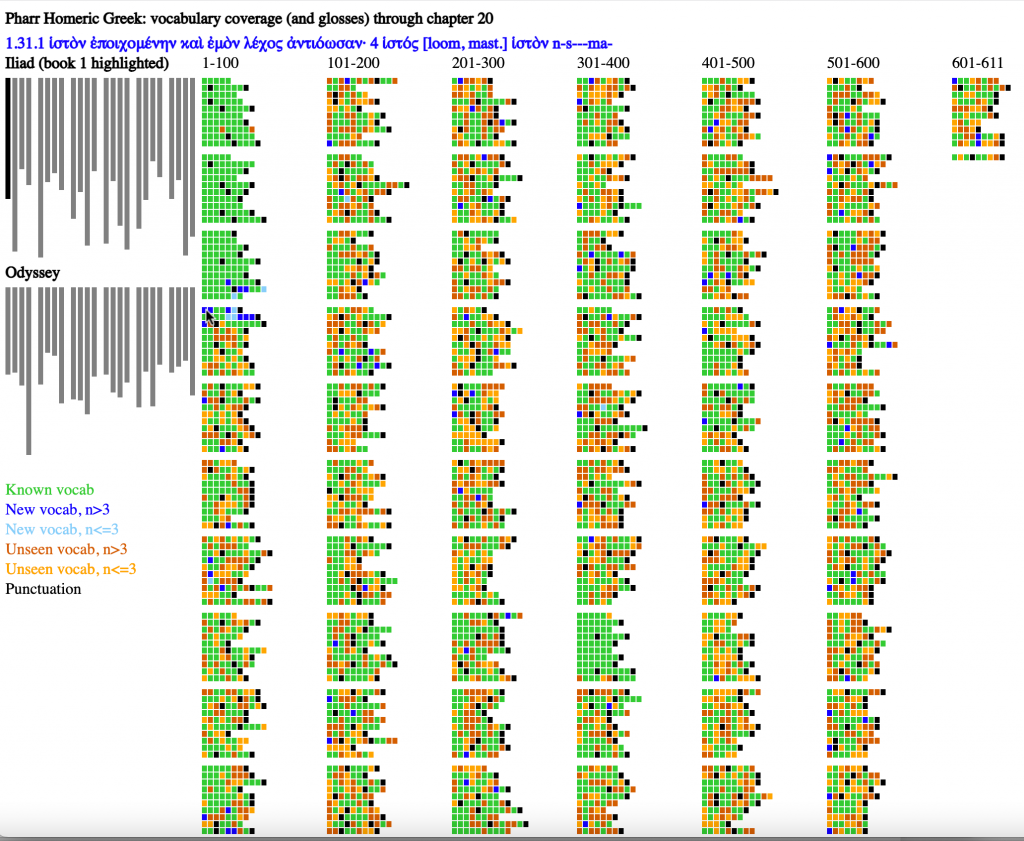

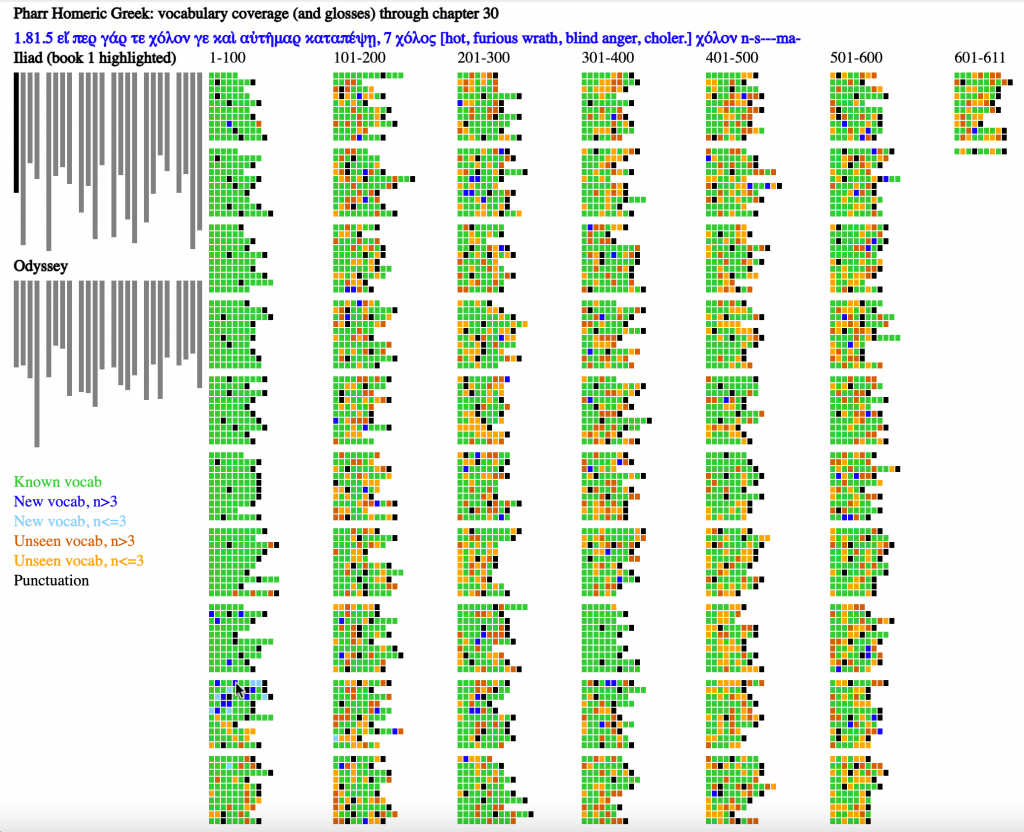

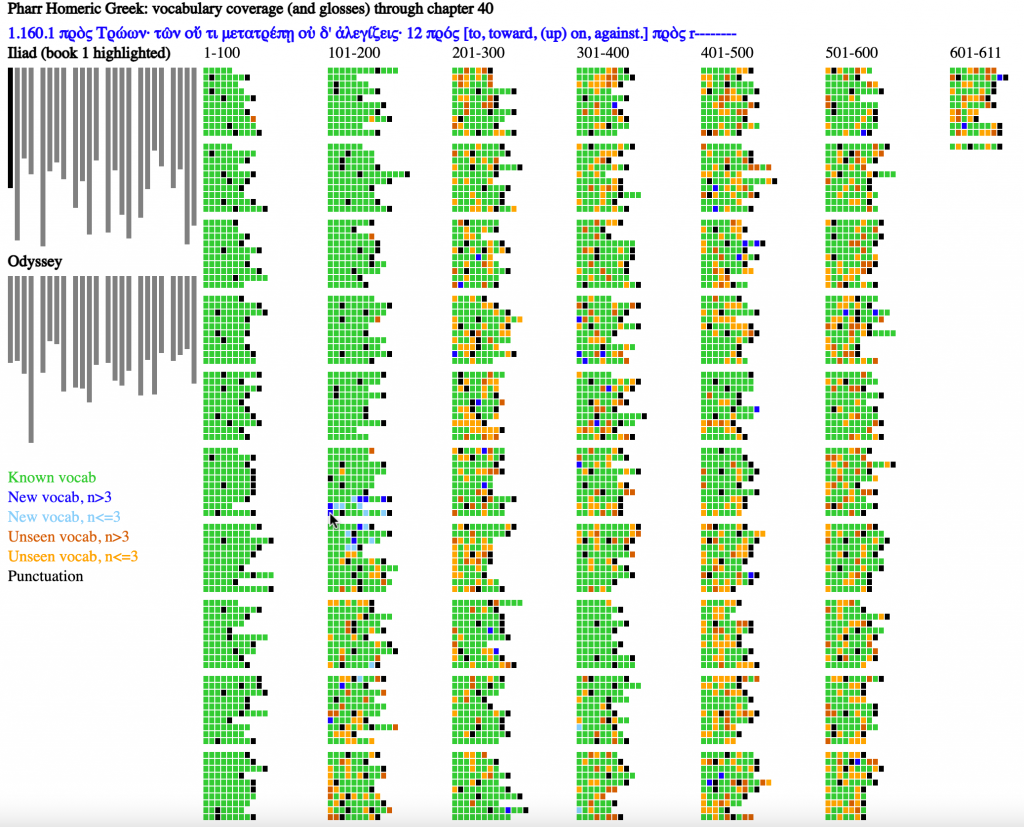

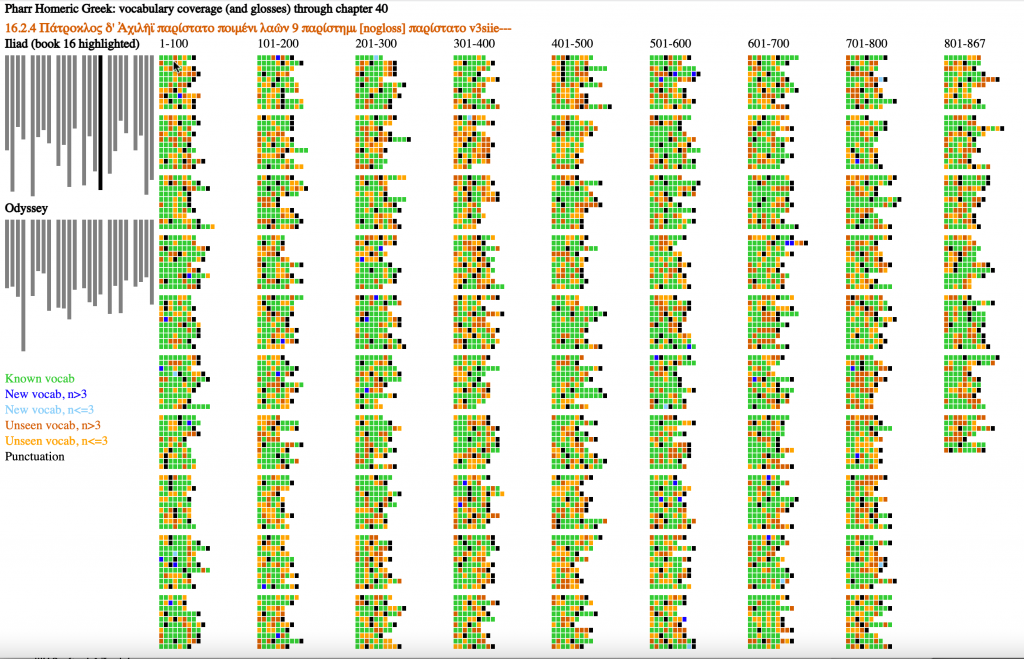

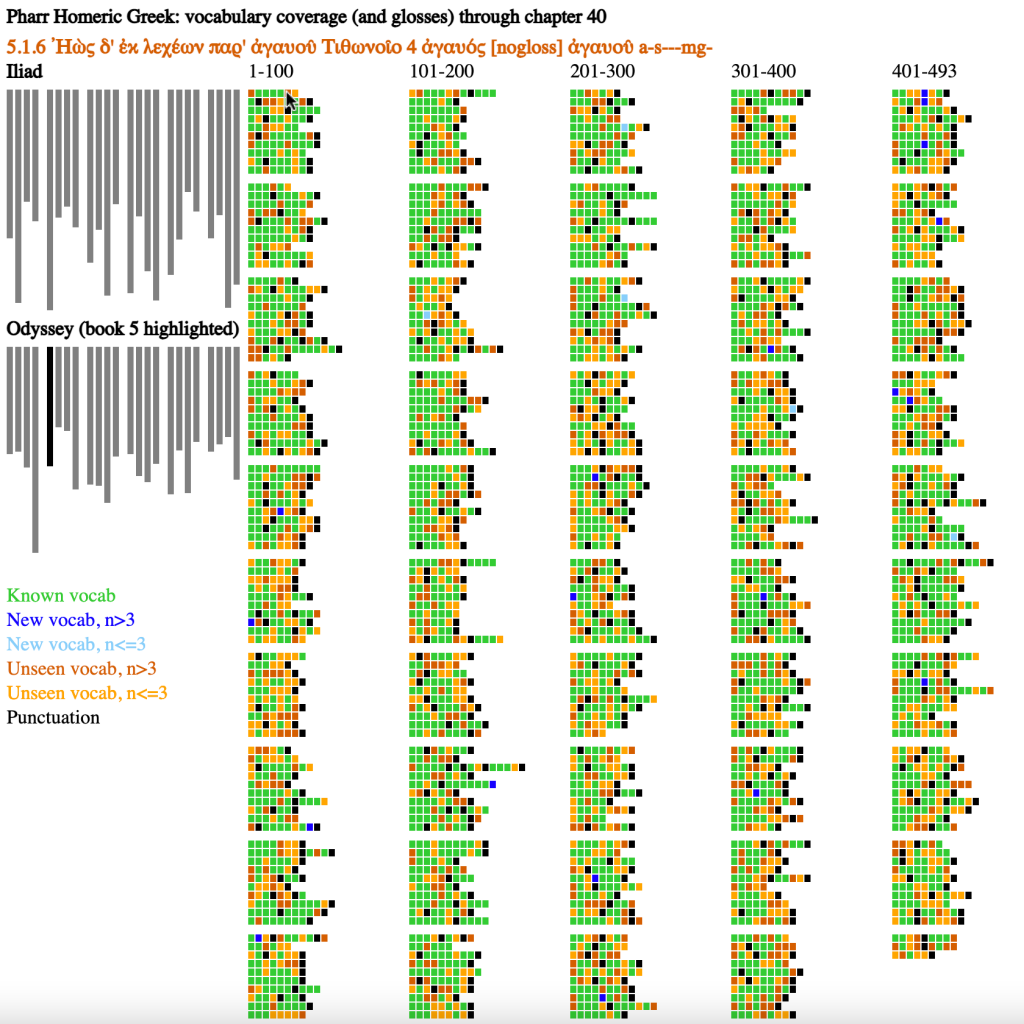

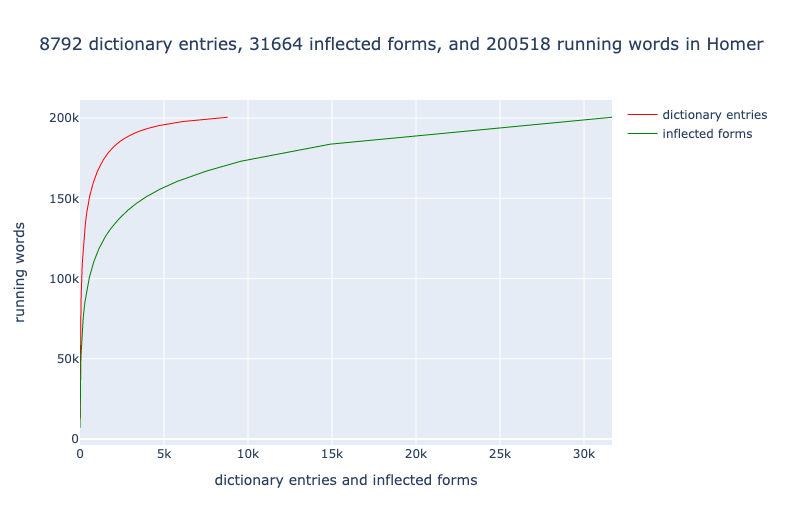

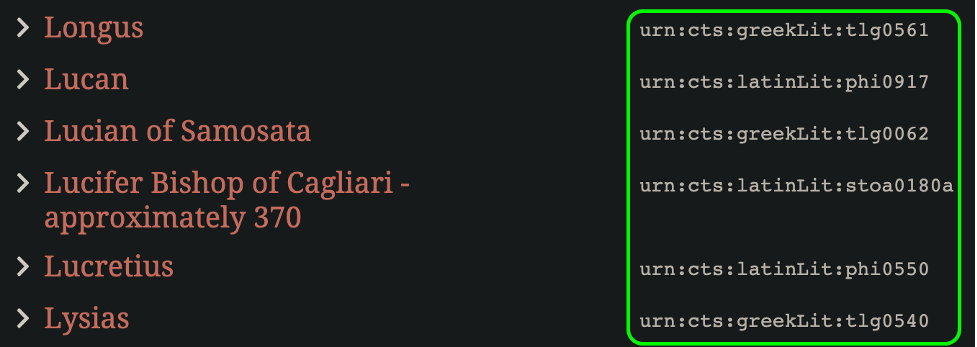

Digital methods, however, fundamentally change our ability (Berti 2019, Schulz 2021). First, we can use natural language processing pipelines such as Stanza and Spacy (Papantoniou and Tzitzikas 2020), multilingual language models such as BERT (Bamman and Burns 2020), machine translation (Kontogianni et al. 2020), most effective for now between modern languages (Bowker 2021), and similar openly licensed resources. In the work that we present, we document the categories which we have found as starting points to augment machine readable texts. The Homeric epics have provided a useful starting point because a particularly rich set of preexisting, open digital resources are available upon which to build. The work with Homeric epic provides us with the framework upon which we are building work with the Shahnameh. We will report on the work with Homeric Greek and summarize progress with pre-modern Persian (building on Pizzi 1881).

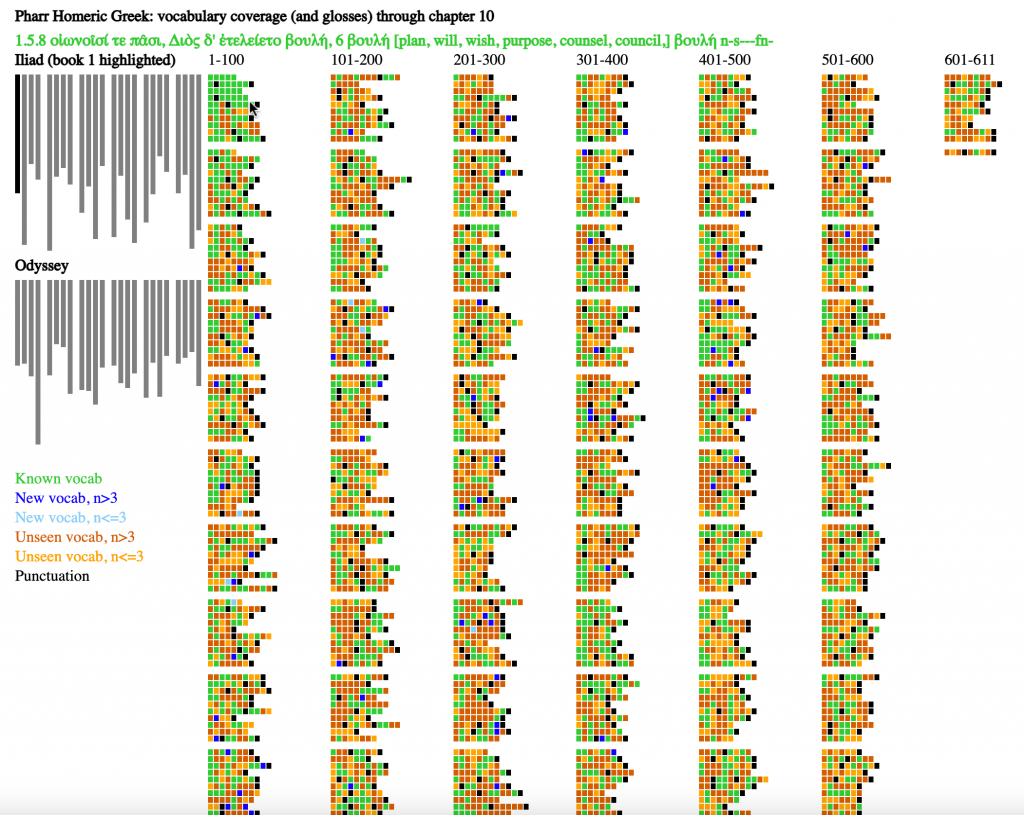

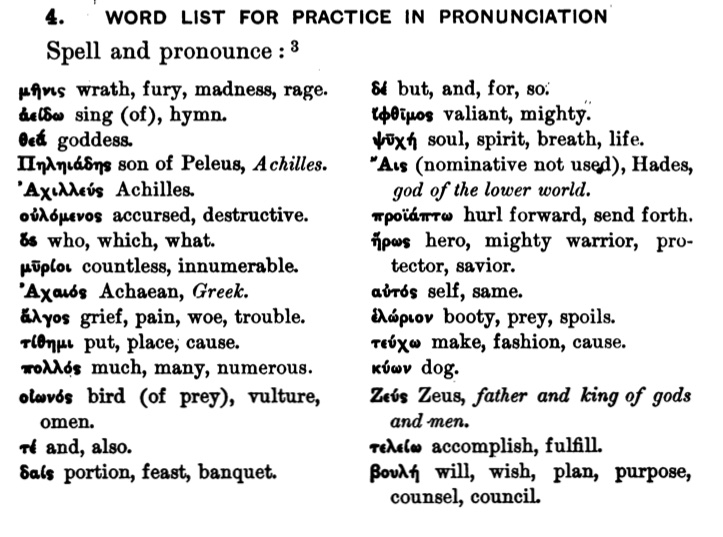

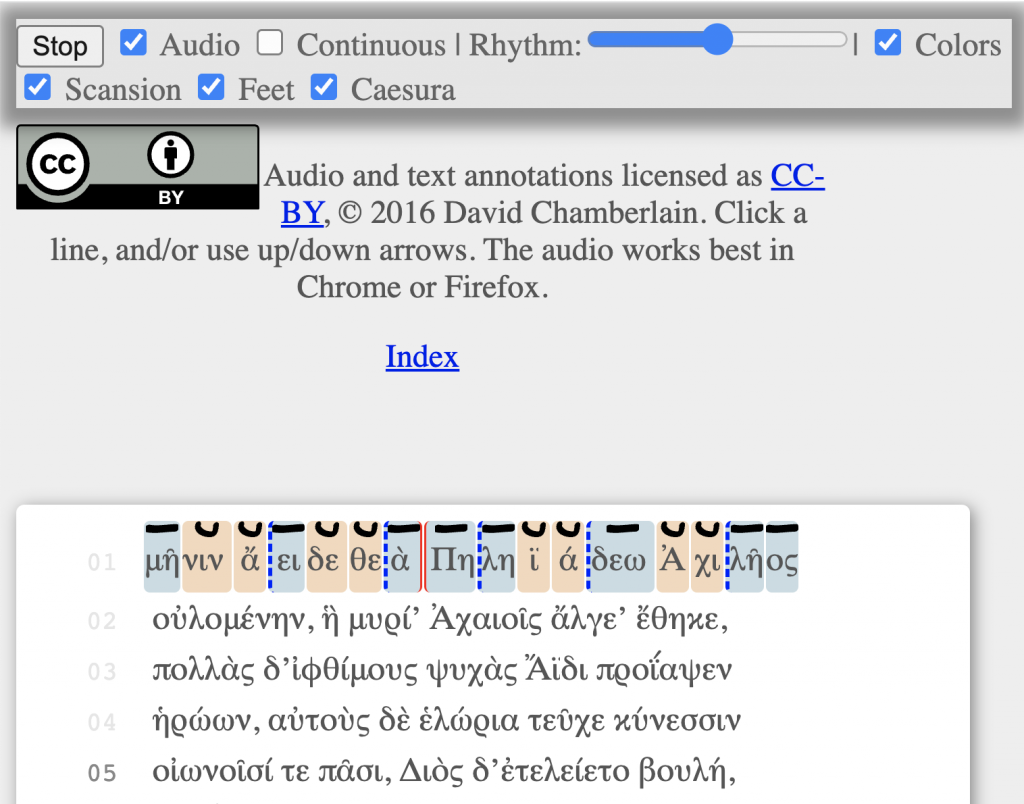

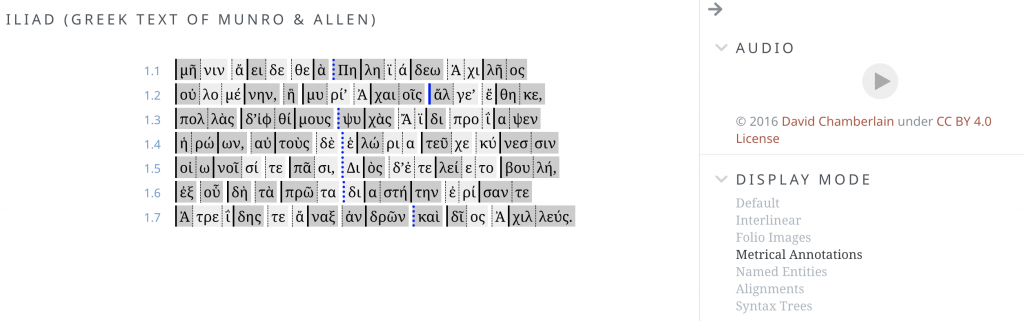

Exhaustive Metrical Analysis and accompanying sound: Machine-actionable metrical analyses (Schoisswohl and Papakitsos 2020) for every syllable in every line of the Iliad and the Odyssey and readings for a substantial portion of the epics are available under an open license (Chamberlain 2021). From the time they learn the Greek alphabet learners engage immediately with the Homeric epic as performed poetry, following metrical diagram and performance.

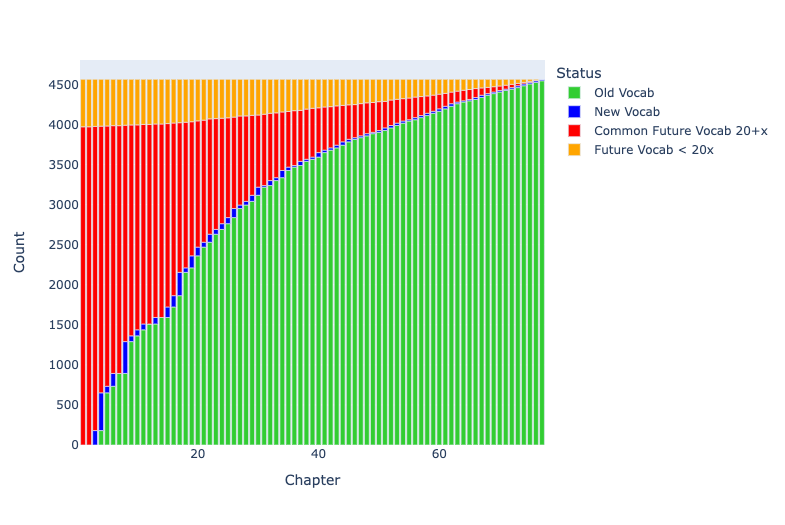

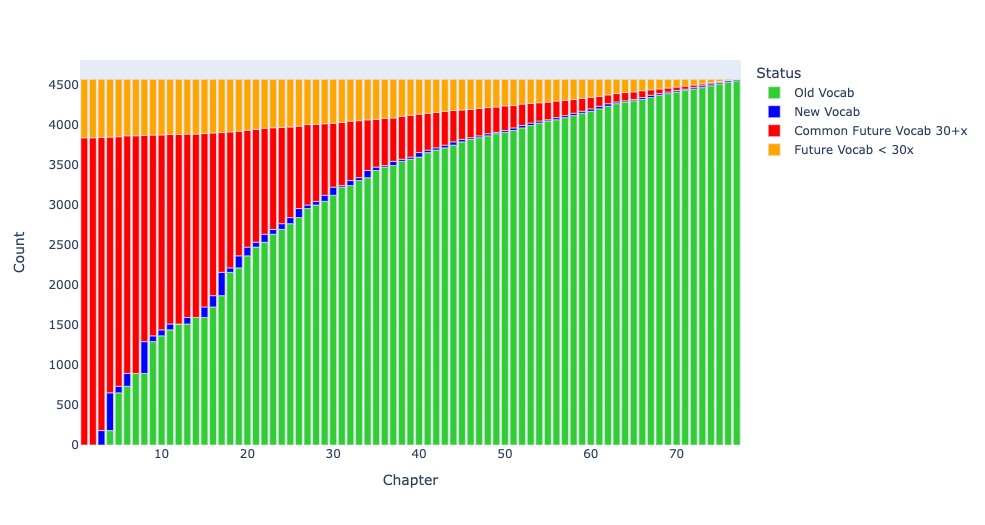

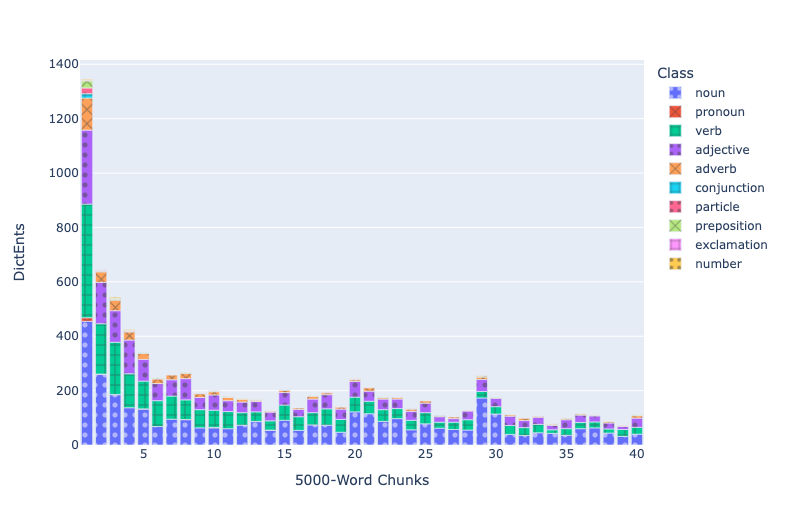

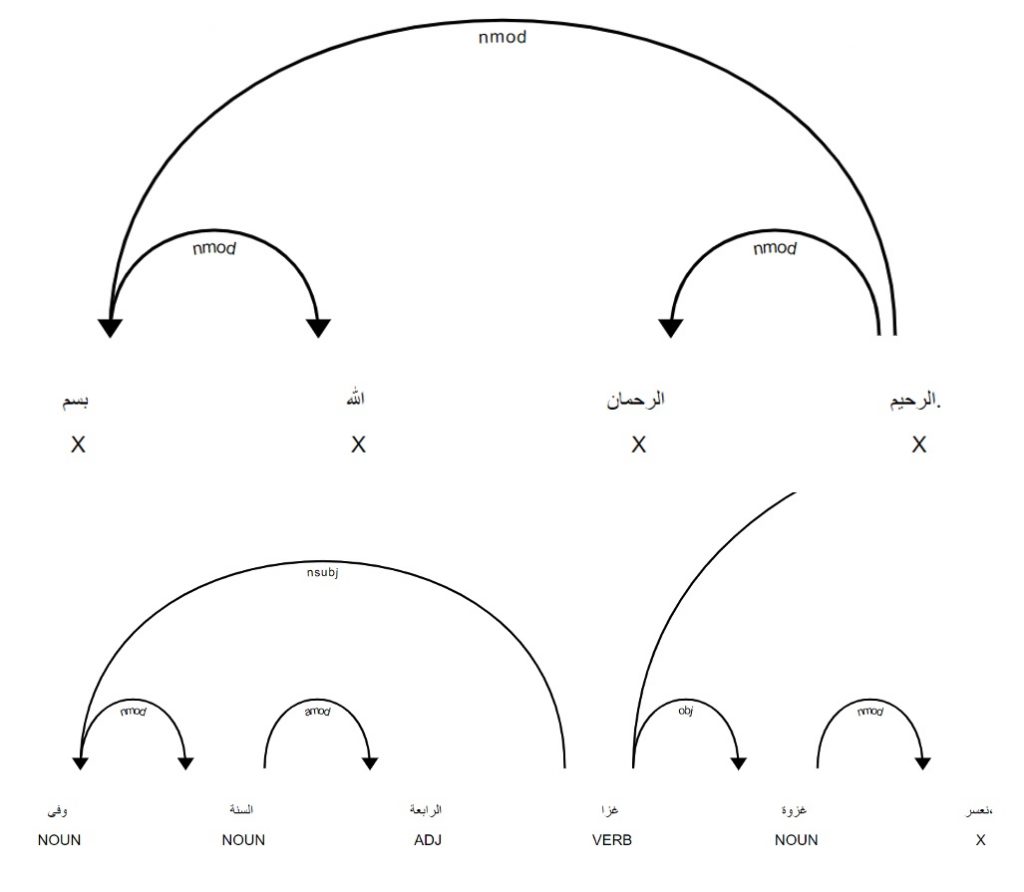

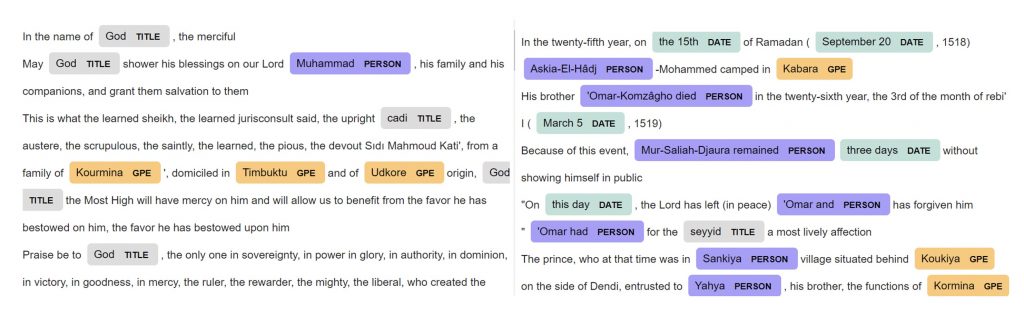

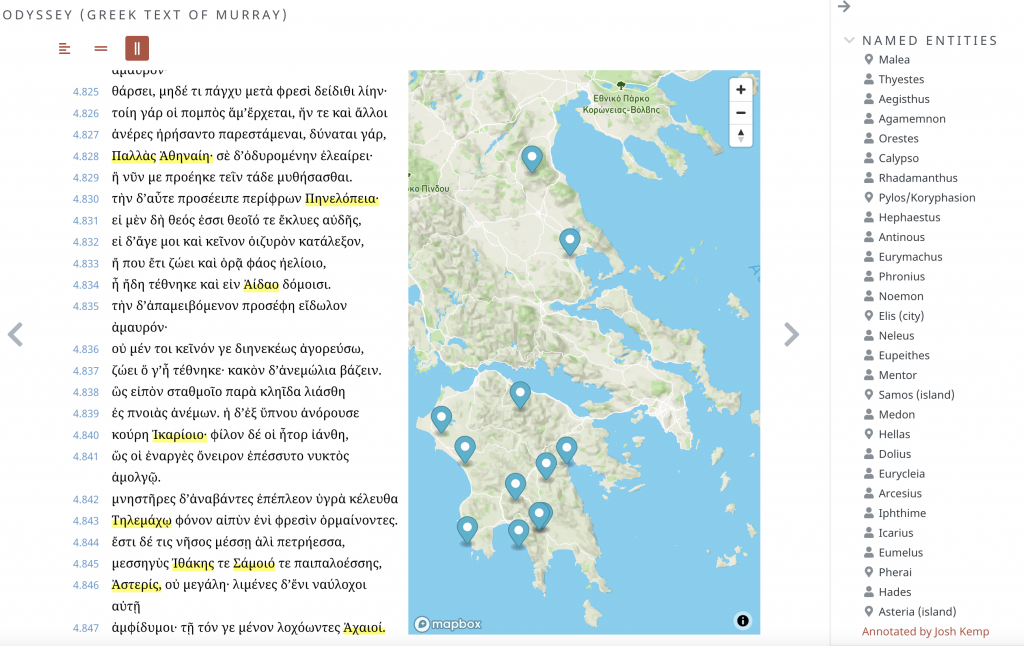

Treebanks document features such as the dictionary entry, part of speech, and syntactic function of every word in a source (Keersmakers, 2019). Treebanks are available for both the Iliad and Odyssey and for more than 1 million words of Greek and Latin (Bamman and Crane, 2011; Celano 2019). We can use these to identify and quantify grammatical structures that students will encounter in the corpus that they will learn.

Paradigm information identifies the morphemes within each individual word and allows learners to see which morphological patterns are most common and to prioritize their learning.

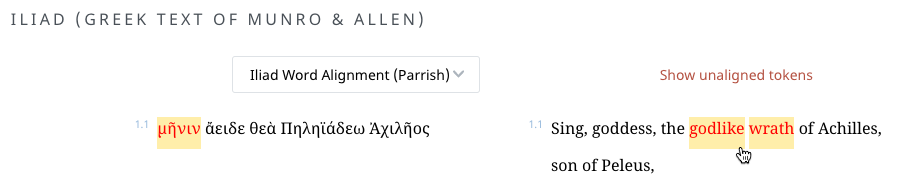

Born-digital aligned translations are created from the start to expose the linguistic structures of a source. From the first lessons, learners can explore the meaning of vocabulary by seeing passages where these words appear (Palladino 2020, Palladino et al. 2021). They can focus on words introduced in a lesson but, in using the aligned translation, they gain constant incidental exposure to words that they have not learned. With translation, the problem of the learner language becomes far more pressing and we can report on the varying challenges of articulating Greek language with translations into English and Persian (Foradi 2020).

Grammatical explanations explain the patterns that learners encounter in the annotations (Mugelli 2021) described above (e.g., the various uses of the dative in Greek or the way we translate the imperfect tense). Grammatical explanations build upon the aligned translations. Grammatical explanations cannot simply be translated but must be adapted to bridge the gap between the target language and the learner language. We report on the differences that arise for speakers of Persian and English.

We will report upon experiences of learners from both Iran and the United States, upon our experiences opening historical students to new audiences (e.g., Classics majors who do not know Greek or Latin) and cross-cultural explanation of content (e.g., Homeric Epic for Persian speakers and Persian poetry such as the Shahnameh for English speakers).

Bibliography

Bamman, D., Burns, P. (2020). “Latin BERT: A Contextual Language Model for Classical Philology.” https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.10053

Bamman, D., Crane, G. (2011). “The Ancient Greek and Latin Dependency Treebanks,” in Language Technology for Cultural Heritage, ed. Caroline Sporleder, Antal van den Bosch, and Kalliopi Zervanou, Theory and Applications of Natural Language Processing (2011), pp. 79–98.

Berti, Monica, ed. (2019). Classical Philology. Ancient Greek and Latin in the Digital Revolution. Berlin: De Gruyter Saur.

Bowker, Lynne. (2021). “Digital humanities and translation studies.” Handbook of Translation Studies: Volume 5 5 (2021): 37-.

Celano, Giuseppe. (2019). “The Dependency Treebanks for Ancient Greek and Latin”. In Digital Classical Philology. Ancient Greek and Latin in the Digital Revolution, edited by Monica Berti, 279–298. Berlin: De Gruyter Saur.

Chamberlain, David. (2021). “A Reading of Homer (work in progress).” Greek and Roman Verse, https://hypotactic.com/my-reading-of-homer-work-in-progress/. Accessed 8 December 2021.

Crane, G. R; Shamsian, F.; et al . (2019). “Confronting Complexity of Babel in a Global and Digital Age.” DH2019: Digital Humanities Conference, Book of Abstracts (2019), pp. 127–138.

https://dev.clariah.nl/files/dh2019/boa/0611.html

Crane, Gregory. (2019). “Beyond Translation: Language Hacking and Philology.” Harvard Data Science Review 1, no. 2. https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.282ad764.

Firdawsī, A. & Khaleghi-Motlagh, D. (1988). The Shahnameh: Book of kings. New York: Bibliotheca Persica.

Firdawsī, A. & Ja’Far, P. C. (1430) The Book of Kings. Tehran: Cultural Heritage Organization. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2021667287/.

Foradi, Maryam. (2020). Engagement with Classical Literature in the Framework of a Citizen Science Project Using Translation Alignment: Date Accuracy and Pedagogical Effectiveness, [Doctoral dissertation, University of Leipzig]

Keersmaekers, Alek. (2019). “Creating, Enriching, and Valorizing Treebanks of Ancient Greek.” 18th International Workshop on Treebanks and Linguistic Theories (TLT, SyntaxFest 2019),

https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/W19-7812

Kontogianni, A., et al. (2020). “Computer-Assisted Translation of Egyptian-Coptic into Greek.” Journal of Integrated Information Management, http://ejournals.uniwa.gr/index.php/JIIM/article/view/4470

Meniński, F. (1680). Thesaurus Linguarum Orientalium Turcicae, Arabicae, Persicae, Praecipuas earum opes a Turcis peculariter usurpatas continens, Vienna: Franciscus a Mesgnien Meninski.

Mugelli, Gloria et al. (2021). “Learning Greek and Latin Through Digital Annotation: The EuporiaEDU System.” In: Teaching Classics in the Digital Age. Kiel: Universitätsverlag Kiel | Kiel University Publishing. S. 25–36. (= Think! Historically: Teaching History and the Dialogue of Disciplines). Online unter: https://macau.uni-kiel.de/receive/macau_mods_00001367.

Palladino, Chiara (2020). ”Reading Texts in Digital Environments: Applications of Translation Alignment for Classical Language Learning.” The Journal of Interactive Technology Pedagogy, Issue 18, December 10, 2020, https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/reading-texts-in-digital-environments-applications-of-translation-alignment-for-classical-language-learning/

Palladino, C., Foradi, M., Yousef, T. (2021). “Translation Alignment for Historical Language Learning: A Case Study.” Digital Humanities Quarterly, 15 (3),

http://digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/15/3/000563/000563.html

Papantoniou, K., Tzitzikas, Y. (2020). “NLP for the Greek Language: a Brief Survey.” SETN 2020: 11th Hellenic Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pp. 101-109.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3411408.3411410

Pizzi, I. Manuale della lingua persiana. Grammatica, antologia e vocabolario, Leipzig, W.

Gerhard (1881). Available at https://archive.org/details/manualedellalin00pizzgoog/

Schoisswohl, O., Papakitsos , E. C. (2020). “Automated metric profiling and comparison of Ancient Greek verse epics in Hexameter.” Linguistik Online, 103(3), 159–177. https://doi.org/10.13092/lo.103.719

Schulz, Konstantin (2021). “Natural Language Processing for Teaching Ancient Languages.” In: Teaching Classics in the Digital Age. Kiel: Universitätsverlag Kiel | Kiel University Publishing. S. 37–48. (= Think! Historically: Teaching History and the Dialogue of Disciplines). Online unter: https://macau.uni-kiel.de/receive/macau_mods_00001368.

Werning, Daniel A. (2009) “Glossing Ancient Egyptian. Suggestions for Adapting the Leipzig Glossing Rules.” Lingua Aegyptia. Journal of Egyptian Language Studies, https://www.academia.edu/1484975/Glossing_Ancient_Egyptian_Suggestions_for_Adapting_the_Leipzig_Glossing_Rules.

Wood, G. (2021, June 9). Princeton Cancels Latin and Greek. The Atlantic. Retrieved December 10, 2021, from https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/06/princeton-greek-latin-requirement/619136/

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible by the Beyond Translation Project, funded by NEH HAA-266462-19, by support from the Data Intensive Studies Center at Tufts University and by the German Academic Exchange Service.