The growing season is a busy time for pollinator scientists. Here’s what members of TPI got up to this summer!

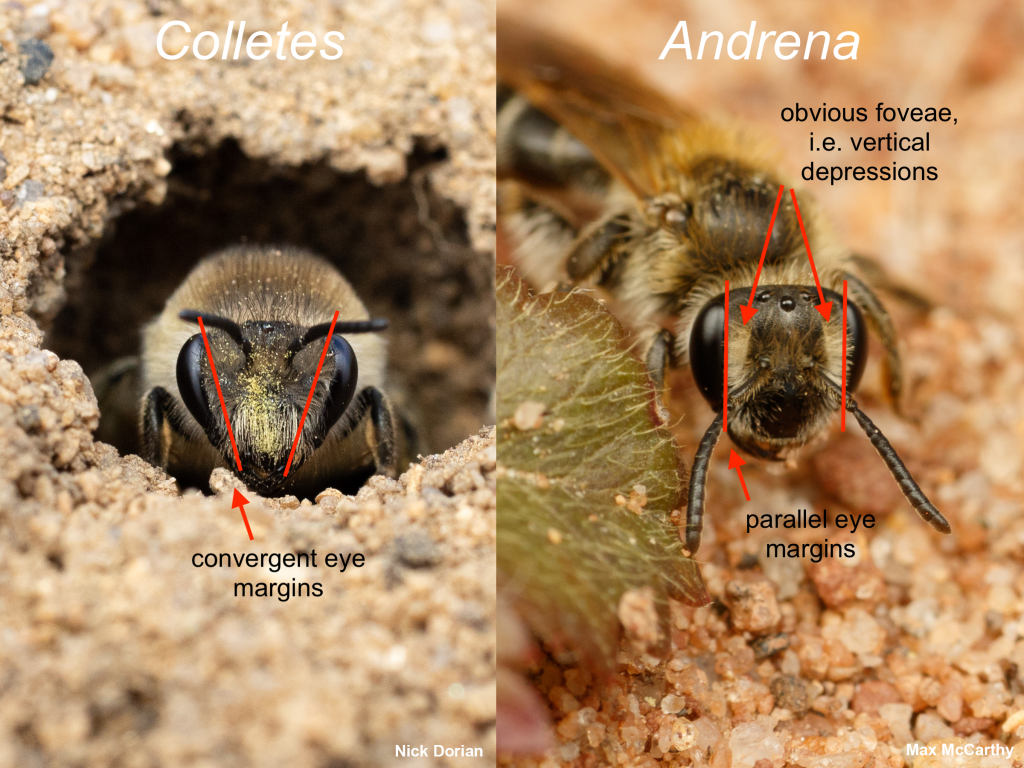

Cellophane bees

Nick, Leslie, and Lydia dug into the secret lives of solitary bees in New Hampshire. They want to know “where does a bee fly in her life?” To answer this, they caught and painted blueberry cellophane bees at nests to identify unique individuals. Then, they surveyed flowers and nesting areas to track daily movements. They painted over 1200 bees!

Bumble bees

Jessie, Lauren and Liana planted hundreds of goldenrod and sunflowers to find out how our growing practices affect the food available to bumble bees — an important native bee that pollinates tomatoes, peppers, melons and more. Bumble bees (like other bees) eat pollen and nectar, and need abundant, high-quality food to fly, pollinate, and raise new bees. They want to know how fertilizer and drought change plant growth, the number of flowers they produce, and the nutrient breakdown of their pollen and nectar. They spent the early summer digging, planting, weeding, and watering and ran a choice experiment to find out which plants bumble bees prefer to visit.

Baltimore checkerspots

Brendan spent the spring and summer studying the impact of the Junonia coenia Densovirus on Baltimore checkerspot population dynamics. He set up an enclosed experiment that exposes caterpillars to a gradient of viral loads and monitored the impact on their survival and reproduction. Later in the summer he continued field sampling for a project that is using a metagenomic approach to investigate whether Lepidopteran viruses are shared between co-occurring caterpillar species. This will help him understand the likelihood of disease spillover impacting species of conservation interest.

Honey bees

Isaac and Greta studied the effect that temperature stress has on the way honey bees arrange their comb stores. They hope to learn how increasing global temperatures will affect the structure of honey bee colonies.

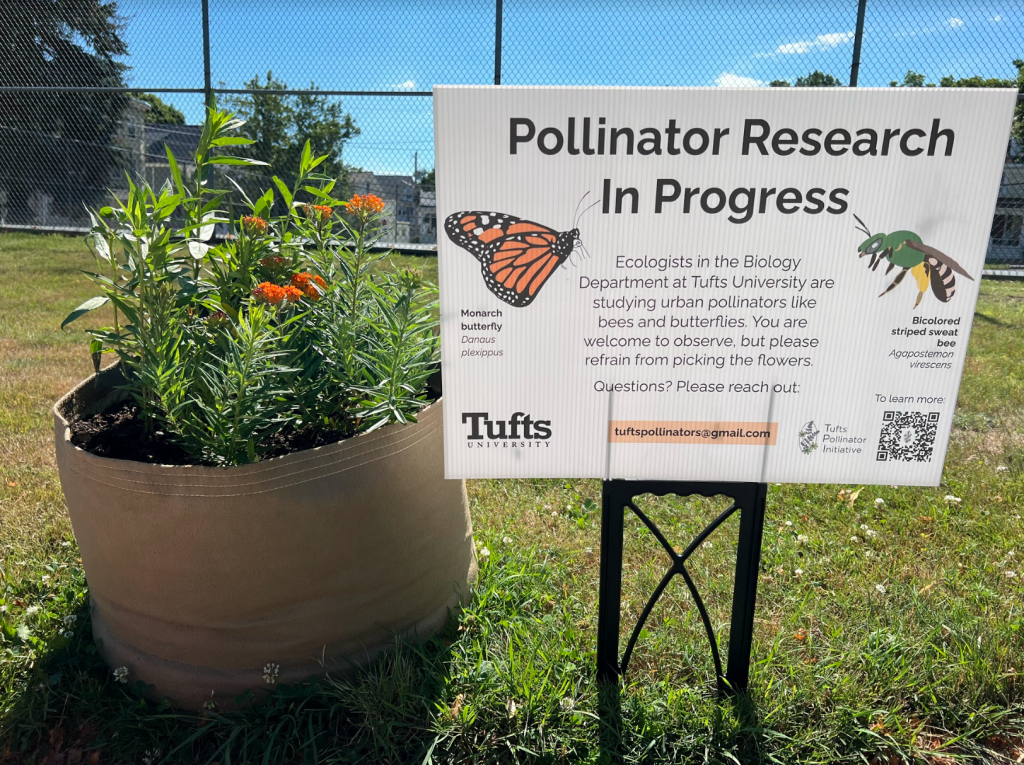

Milkweed visitors

Atticus, Karen, and Kristina are looking at pollinator usage of milkweed in urban environments. Atticus and Karen observed monarch egg-laying behavior on milkweed, the monarch butterfly’s host plant, to see if it changes depending on surrounding landscape contexts, such as differing neighborhood flower garden densities. Kristina looked at milkweed flower visitors to see how visitation rates and species richness are affected by flower garden densities. You may have seen their pots at various park locations in Medford and Somerville!

Sweat bees

Chloé, Nick, and Aviel studied sweat bee (Agapostemon virescens) movement on Tufts’ campus. They want to know whether roads act as barriers to foraging bees. To answer this, they set up squares of four pots of coneflower bisected by roads at three sites on campus. At these sites, they caught and painted bees to identify unique individuals and recorded ongoing traffic.

Yellow-faced bumble bees

Across the country in California, Sylvie is studying the difference in life cycle patterns of Bombus vosnesenskii, the yellow faced bumble bee. Sylvie is interested in how life cycle timing of this bumble bee varies across its range. In the Sierras, B. vosnesenskii displays the characteristic timing of bumble bees – a queen emerges in spring, a colony grows over the summer with female workers, and at the end of the summer the queen stops producing workers and starts producing new queens and males. Then, the mated female queens overwinter underground! Sylvie is getting to discover firsthand the timing of Bombus vosnesenskii life cycle on the coast–and how it compares to timing in the mountains–since it has not yet been characterized!

Pipevine swallowtails

James and Kaitlyn mated adult pipevine swallowtails and tested how growth rates in their offspring may be affected by differences in ambient temperature. These females laid eggs on Dutchman’s pipe and they collected those eggs to put in different thermal treatments. They will monitor those larvae until they’re ready to become adults themselves.

Monarch butterflies

Also in California, Emily studied monarch butterflies in urban gardens in the San Francisco Bay Area. Most people know monarchs for their impressive yearly migrations. Recently, however, year-round breeding ‘resident’ monarchs have also established in coastal cities in Northern California. These residents are associated with non-native milkweeds – namely Tropical Milkweed (Asclepias curassavica), which do not die off in the winter as the native species do and therefore provide breeding habitat throughout the year. We don’t yet know yet how resident and migratory monarchs interact with one another in urban gardens, and what the consequences of these interactions may be. In her research, Emily hopes to understand whether the resident monarchs in urban gardens are a population that is independent of the migratory one, or whether the presence of residents and their non-native host plants are contributing to overall monarch declines in the West.