Building Coalitions to Prevent and Combat Human Trafficking: An Interview with Anti-Human Trafficking Expert, Ruth Freedom Pojman

Building Coalitions to Prevent and Combat Human Trafficking: An Interview with Anti-Human Trafficking Expert, Ruth Freedom Pojman

The following is an edited version of a conversation with PRAXIS:

Could you please describe how the concept of “human security” has developed and how it relates to your field of work?

During the Cold War period people started to realize that the traditional approach to national security was not adequate to deal with all the challenges the world was facing. It was during this time that people understood that thinking about areas like human rights, economic opportunity, the environment, transnational crime elements as well as traditional threats was key to promoting security for all.

I started my career after the end of the Cold War, working in the post-Soviet space. I observed that particularly in places like the former Soviet Union, while there were new freedoms and opportunities, this time was also a period of deep transition, which included social and economic disenfranchisement, economic and political instability and an overall feeling of communal insecurity. It was literally as if the floor fell out from underneath people. Much of the population in the Soviet Union was highly educated and had job security and with the collapse of such a massive system, they then found themselves with no job prospects, also facing the rise of organized crime and corruption. People were politically, socially and economically vulnerable and sadly in some cases became involved in human trafficking, as perpetrators or victims.

In your experience, are governments designing anti-human trafficking programs with human security at the core or are there different central motivations?

It really depends on the actual situation on the ground in the individual states, on the degree of their political will to address the challenge, and on concerted efforts by a range of stakeholders – both local and international.

In the beginning, it was more about getting governments to first understand and recognize the gravity of the human trafficking problems in their own countries. Often a particular event or tragedy acts as a catalyst for a government and other actors to take action. I was on the ground in the late 1990s and early 2000s in Central Asia and one of the first people to do research and reporting on human trafficking in the region. Evidence-based documentation and awareness efforts have contributed to the development of more substantial progress by individual countries, and improved global efforts and legislation to tackle the problem. And, thanks to the adoption of the 2000 Palermo Protocol by the United Nations, the 2014 Forced Labour Protocol, and multi-stakeholder action around the SDG targets 5.2, 8.7 and 16.2, we are making progress in preventing, suppressing human trafficking, protecting the victims, and punishing the perpetrators.

The degree of attention and care given to human trafficking issues depends very much on the priorities and values of the countries themselves. The level of political will is also extremely important as is the power of an individual to drive and shape policy, or pressure from citizens and even businesses to tackle this challenge – all taken together can make a big and positive impact.

And, we have also learned the importance of factoring-in the views and experiences of survivors of trafficking into policy making and action plans. For example, there is now a U.S. Advisory Council on Human Trafficking that allows survivors to make recommendations to the President’s Interagency Task Force to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons. Their involvement at all levels is making national and international anti-human trafficking efforts all that more successful and sustainable.

In this current climate, of states turning more inward, is this affecting cooperation and coordination when addressing human trafficking? Have we gotten better at working together on these common issues or is the work becoming more difficult?

The fact is that all countries have many complex issues and challenges today that are competing for each government’s time, money, attention and effort.

Human trafficking is first and foremost a criminal issue and a low risk ‘lucrative business’. Unfortunately, as it is often noted, traffickers still work better together than those fighting them.

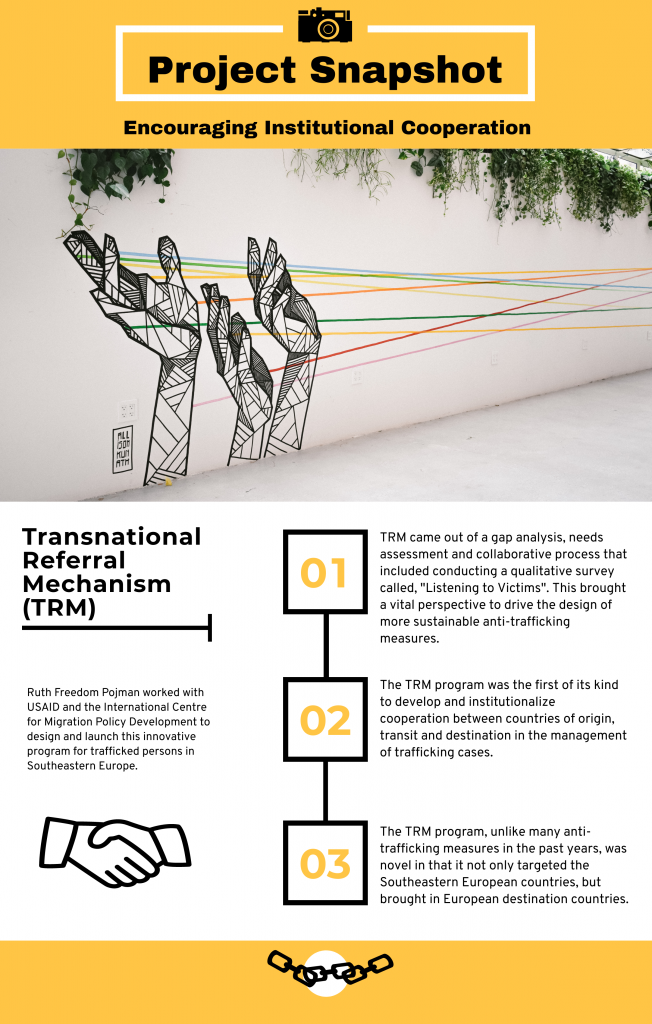

Fortunately, there are now good cooperation mechanisms in place like the UN Inter-Agency Coordination Group against Trafficking in Persons (ICAT), the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE)‘s Alliance against Trafficking in Persons, and Alliance 8.7. The latter is a multi-stakeholder group that engages civil society, governments, workers organizations and business networks seeking to eradicate forced labor, child labor, modern slavery and human trafficking from their supply chains, and has created a knowledge platform to guide action. There are also country level cooperation platforms, such as national referral mechanisms, which work to improve identification of human trafficking cases, the capacity of law enforcement on prevention and detection, and as well as provide meaningful protection to trafficked persons. Finally, when at USAID we worked with ICMPD to develop transnational referral mechanisms, an agreement for comprehensive cooperation to improve the protection of trafficked persons in cross-border cases.

Unfortunately, some of the biggest challenges to progress on anti-human trafficking reform include the loss of qualified, passionate and knowledgeable personnel who frequently transfer to other employment. Individual people make a big difference, as does the continuity of effort and knowledge. That also goes for national leaders. For example, the UK’s former Prime Minister, Theresa May, cared deeply about combatting modern slavery and made strides through making this a priority of her Government.

While there are many circumstances that make individuals vulnerable to human trafficking and states ineffective in dealing with the associated problems, what do you understand as some of the common root causes/main reasons for high levels of trafficking in certain countries (i.e. corruption, weak judiciary, patriarchal cultures)?

Circumstances and root causes can vary significantly based on context. While I was with USAID, we spent a lot of time studying and trying to address root causes and design programs for prevention. Some of the more general trends were the economic dislocation in the former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia following the fall of communist regimes where societies were also transitioning to market economies and democratic governance. There was also a sort of breakdown of values. Young people became cynical seeing that they needed to for instance pay for grades and in some places, and witnessed a lack of accountability by some of their local or national officials. There was a return to more patriarchal systems in some of these countries and women and girls became more subjected to activities like trafficking in this aftermath. Men were also trafficked and exploited at a higher rate than in other regions of the world, facing even stronger social stigmatization in many societies.

When working with USAID I tried to understand the local context and sensitivities in which we were operating, and to coordinate efforts across development sectors to integrate anti-trafficking into economic growth, labor standards, democracy and governance benchmarks and dedicated programs to empower women, promote more access to economic opportunity and legal services, and to prevent human trafficking by addressing its root causes and making it a less profitable crime. In 2008, I was involved in organizing the first international event on leveraging anti-laundering regimes to fight human trafficking.

You’ve had such a diverse career. What are some of the highlights or initiatives you’re proudest of?

When I started in this field in 1997 I was shocked by what I found and wanted to do something about it so I tried to promote evidence-based policy making and translate my research into practical work. As a result, I was the first person to undertake anti-trafficking research in Central Asia and worked with countries from Russia to the United States to combat related corruption and organized crime.

I’ve been honored to conduct training work involving NGOs, the media and governments. For example, I organized the first event focused on human trafficking in conflict settings at the U.S. Military Academy. Subsequently I’ve been invited to present on the issue of human trafficking in the contexts of managing border security, migration, human rights and peacekeeping to military commanders from several countries.

One of the most meaningful challenges has been to work on standard-setting. For example, I helped Lockheed Martin craft their code of conduct to avoid human trafficking, throughout their workplaces and supply chains. While working for the OSCE, (the largest regional security organization comprising 57 participating States from Vancouver to Vladisvostok), I directed the development of a model law and model guidelines on measures that governments can take on preventing human trafficking for labor exploitation in supply chains, and coordinated internal efforts revise its own policies and procedures, to ensure that the organization’s own supply chains were free of forced-labor and human trafficking. This resulted in the OSCE becoming the first international organization to leverage its own procurement practices, to ensure that it does not contribute to any form of human trafficking through contracting goods and services, thereby holding itself accountable.

Working as an anti-human trafficking professional can be emotionally challenging. How do you personally deal with fatigue in this line of work?

When I started working on this issues, while with the International Organization for Migration, I worked directly with survivors of human trafficking, before official programs were really out there. I experienced secondary trauma. To adequately support survivors, I discovered that you really need to have a background as a social worker or psychologist, or to be a survivor yourself. It takes special training and experience to be an effective case worker, to support survivors in their road to recovery, and also their families. For example, I was contacted by the parents of a missing woman in what became a transnational trafficking case. We assisted with an international investigation eventually to discover that she had been brutally murdered. I was the one to relay the tragic news to the parents. This deeply affected me, and I sadly have had too many colleagues, contacts and friends whose lives have been threatened due to their work protecting victims, prosecuting cases, and curbing human trafficking and related crimes. This takes a personal toll; one is never the same.

Over time, I reassessed my strengths and talents found that I was better suited for developing programs and policies, connecting and engaging stakeholders and training key actors. For example, I advocated that the voices and views of survivors be considered by policy-makers, law-makers and by law enforcers, so that their anti-trafficking work is more comprehensive, effective and inclusive, resulting in the ICMPD-USAID publication “Listening to Victims”.

For me personally, what helps me most manage work fatigue and stress are keeping fit and healthy, meditation, being around positive people, and being in contact with culture and nature. I don’t shy away from difficult professional endeavors, but I try to pair them with life affirming activities that help to maintain an inner balance.

Ruth Freedom Pojman is a global leader in the fight to end all forms of human trafficking and promote human rights. She has over 20 years of experience working for organizations such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, International Organization for Migration, United States Agency for International Development, Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, the Global Fund to End Modern Slavery, and currently she is a Consultant for Winrock International. Her expertise areas include forced labor, sustainable public procurement, supply chain transparency, anti-corruption, Track II diplomacy, stakeholder engagement, and risk analysis. She has worked in Central Asia, Eurasia, Europe, Asia and North America with international organizations, civil society, national governments, including defense, and the private sector. Ms. Pojman recently started her own consulting company where she advises agencies, corporations, and organizations on ethical and social responsibility matters with regard to policy, regulation and practice on human rights, illicit trade, forced labor, human trafficking, modern slavery and sustainable supply chains. In addition, she serves on advisory boards and steering committees, including of the Responsible Business Alliance’s Responsible Labor Initiative, and the Berlin based organization Your Public Value.

What a great interview. What ab inspiring woman you are, Ruth Freedom!

Ruth is filled with real purpose and dedication to help those in greatest need. I will always admire her spirit and her ability to help end one of the most heinous crimes against humanity, ie human trafficking for whatever purpose.