Certain medieval objects have been especially valued, acquiring layered meanings over time. This is the case with the so-called Virgin of Vladimir icon and the bronze horses of San Marco, to name but two famous examples. These objects have been reimagined in local contexts in order to promote certain narratives over the course of their long lives and afterlives.

The Virgin of Vladimir is a bilateral icon that shows the Virgin Eleousa (or the Virgin of Tenderness) with the Christ Child on one side, and an image of the Hetoimasia (a symbolic representation of the Second Coming of Christ) with the nearby instruments of Christ’s Passion on the back. The image on the front of the icon, however, is the most poignant. It shows the Christ Child reaching for his mother, touching his cheek to hers while extending his right arm around her mantle. The Virgin gently cradles the child in her arms and bends her head to reach his cheek while looking out to the viewer. Her gaze is both loving and sorrowful, as if anticipating the suffering that followed in her son’s death and subsequent resurrection.

The icon’s technique and iconography suggest a Byzantine origin. It arrived in Kyiv likely as a diplomatic gift from Constantinople during the first half of the twelfth century (ca. 1130). In 1155, it was transferred to Suzdal and Vladimir, and then to Moscow. This occurred sometime after 1326, when Moscow began to assert its religious and military presence in the region, subsequently centering the historical narrative in this locale. The icon is supposedly a miracle-working image that protected Moscow from military attacks in the Middle Ages. Interestingly, the physical movement of the icon between the centers of Rus and Moscow corresponds with the transfer of religious, political, and ideological power, as well as its eventual concentration on the Kremlin from the fourteenth century onward.

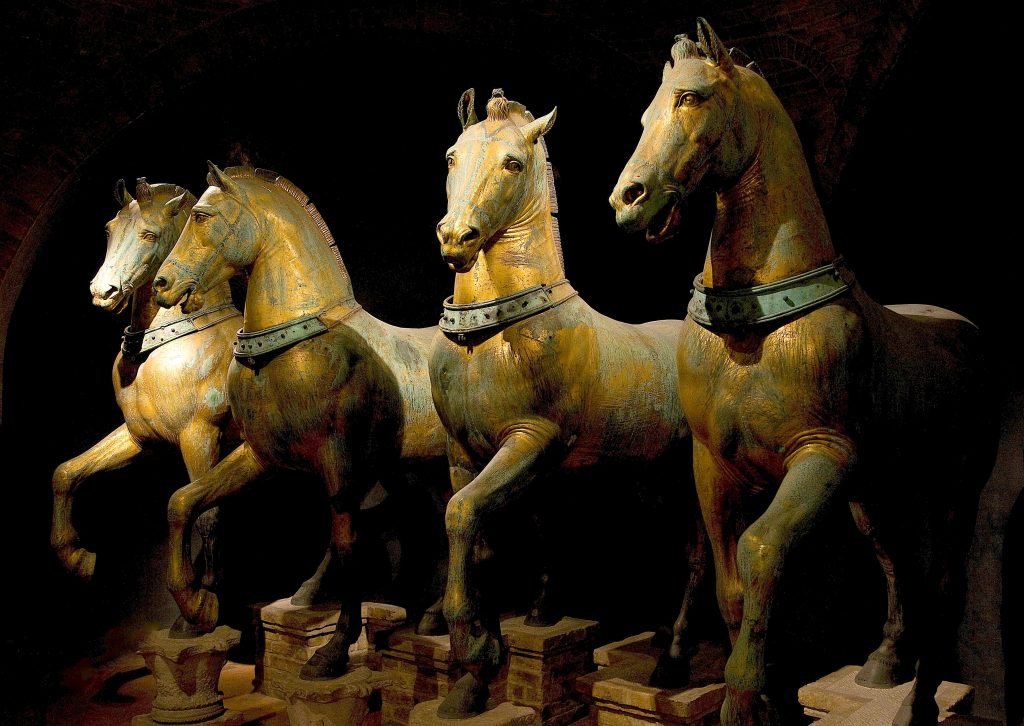

The reimaginings of the Virgin of Vladimir icon are not unlike the transformations of the four bronze horses of San Marco in Venice during the Middle Ages. The well-known and valued horses were supposedly removed from imperial Rome and brought to Constantinople in the fourth century, then brought to Venice by the victorious crusaders who sacked the Byzantine capital in 1204. The social memories and triumphant identities embedded in the statues were thus conferred on new cities and localized power structures. They served as symbols of Rome lost, refashioned, and regained.

The bronze horses of San Marco and the Virgin of Vladimir icon capture the power in the reappropriation of art, history, and memory, underscoring how the movement of objects and their reimaginings can transform sacred spaces and ruling ideologies across time and space.