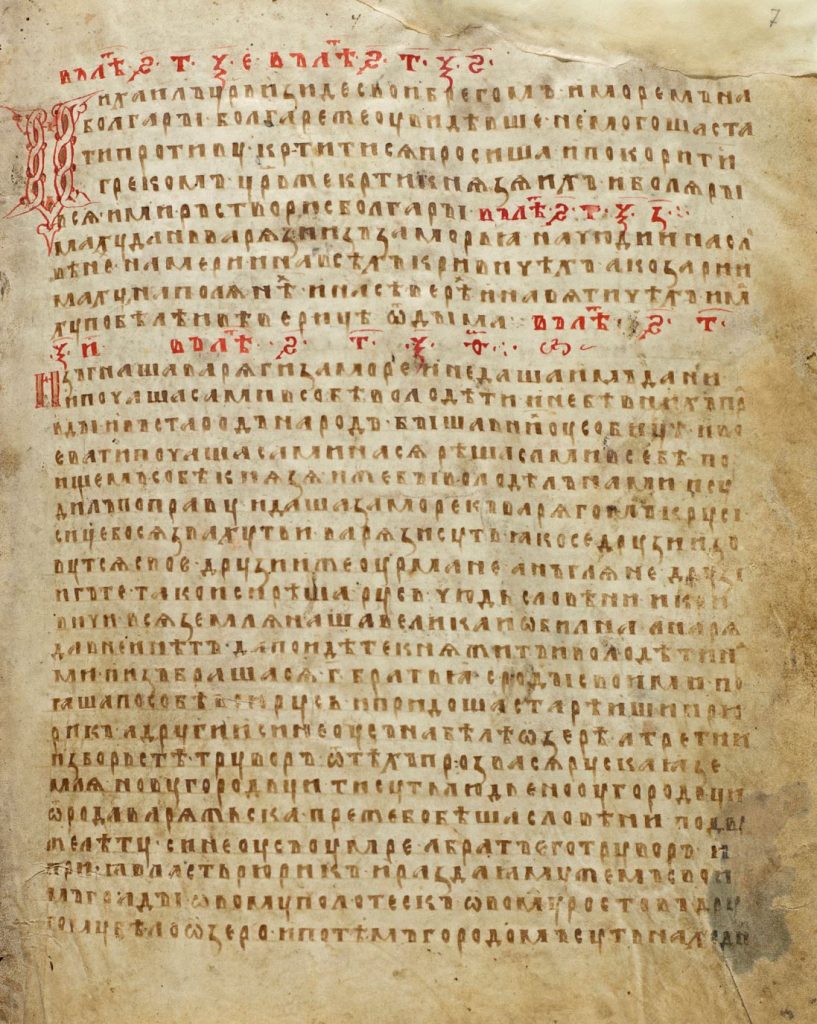

By the thirteenth century, the kingdom of Kyivan Rus had begun to fracture into disjointed principalities, ending a period of political unity that had made Rus the largest kingdom in medieval Europe by territory. The 1204 sacking of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade further alienated the area as the pope declared war on all non-Latin churches. These events left Rus vulnerable to a new enemy that appeared in the 1220s: the Mongols.

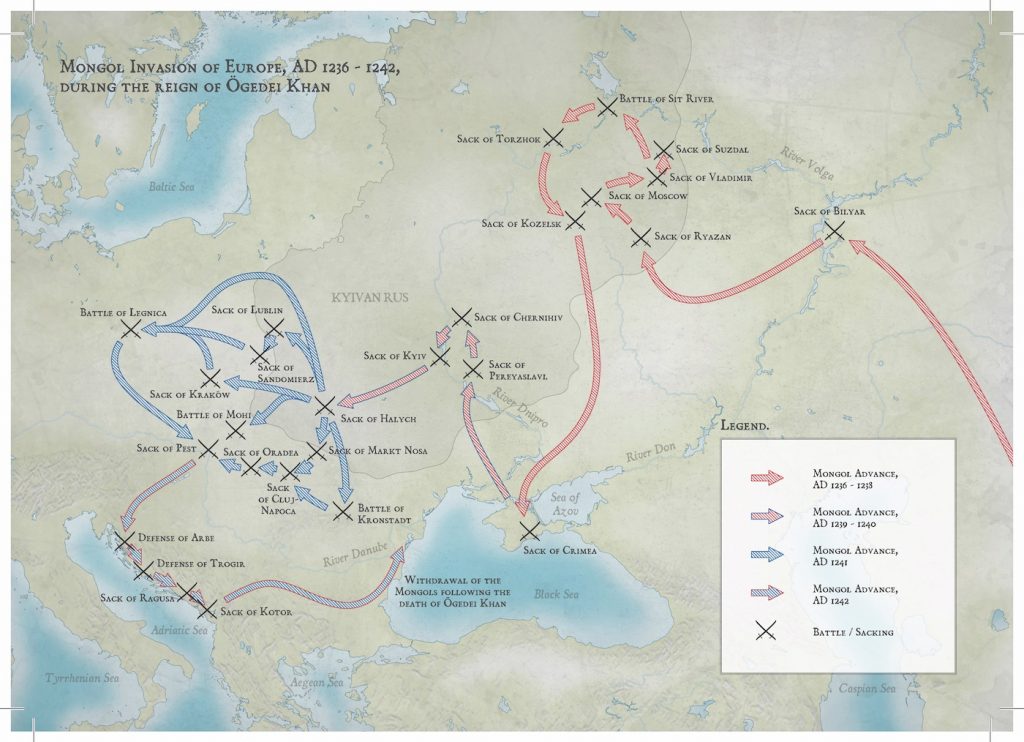

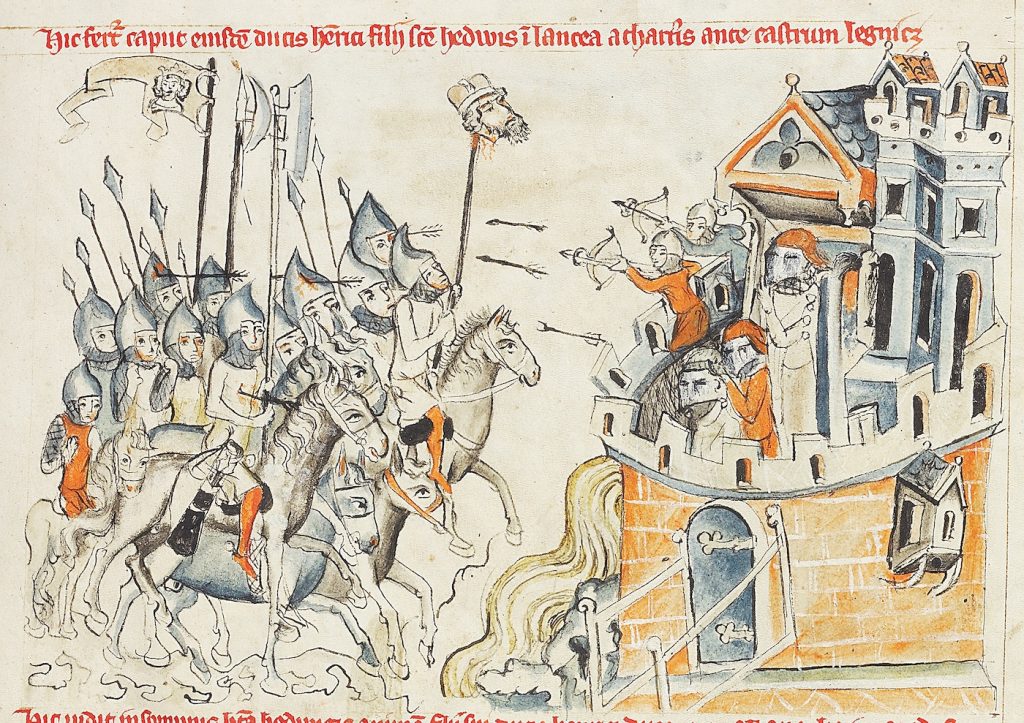

Although the Mongols (referred to as “Tatars” in Eastern sources) easily defeated the Rusians in the 1223 battle on the Kalka River, they left the area and did not return until 1237, when they began their campaign to conquer the entire region. The Mongol army under Batu Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, took Kyiv in 1240 and overran almost all major cities in the kingdom with the notable exception of Novgorod in the north, which preemptively surrendered to the Mongols under Alexander Nevsky (r. 1236–59).

Nicknamed the Golden Horde, the Mongol rule over Rus would last over two centuries. Basing their occupation on their nomadic lifestyle, the Mongols often controlled the conquered areas through remote rule, allowing the Rus princely infrastructure to remain intact, albeit subservient to Tatar forces. Despite the Mongol raids, parts of Rus grew in prosperity during this period by trading along the Silk Road. The Orthodox Church also thrived under the Mongols’ religious toleration. In the second half of the fourteenth century, Moscow emerged as a leading power due to the adoption of Mongol institutions under Grand Prince Daniil (d. 1303), the son of Alexander Nevsky, and his son Iurii (r. 1303–25). Moscow’s flourishing allowed their forces to defeat the Golden Horde at the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380, although Mongol control continued in Rus until the Great Stand on the Ugra River in 1480.

Scholars have debated the influence of Mongolian domination on Kyivan Rus. Russian scholars, who have termed the period the “Tatar Yoke,” have generally denied any impact on Russian society due to the Mongols lack of contact with local populations. However, American scholars have asserted that despite the Mongols’ remote ruling strategy, intercommunication frequently occurred. The Mongol influence was manifold, significantly affecting the rise of modern Russia and Eastern Europe more broadly.