It is well established that flying is emblematic of inequality. This is true of mobility more broadly. As Tim Cresswell writes in his book On the Move: Mobility in the Modern World, movements of people are “products and producers of power (and thus their attendant inequities).” In terms of fossil-fueled mobility and it relation to climate breakdown, no form of mobility reflects such inequities more than flying (with the exception of luxury cruise ships).

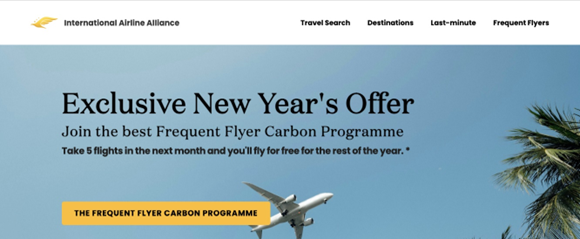

A new website—a spoof produced by Stay Grounded and the New Weather Institute—highlights frequent flyer programs as especially flagrant examples of the injustice associated with flying and the harmful impacts it gives rise to. The top of the site invites people to “take 5 flights in the next month and you’ll fly for free for the rest of the year.” Only when one scrolls down does it become evident that the site is criticizing such programs and proposing a frequent flyer levy “for the people and companies that fly and pollute the most.”

Academics who fall into the frequent flyer category engage in airborne travel for a variety of reasons. One is that aviation’s efficiency (of a narrowly construed sort) makes it attractive: it allows one to traverse considerable distance at high speed. It also entails considerable ecological harm.

Such concerns informed the decision of James Lamb, a Lecturer in Digital Education at the University of Edinburgh, to travel by train between Scotland and Switzerland for an international conference. In a chapter in an edited volume (“The Postdigital Learning Spaces of a Transcontinental Train Journey,” in Postdigital Learning Spaces: Towards Convivial, Equitable, and Sustainable Spaces for Learning, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024: 119-137), Lamb draws upon “an autoethnographic exercise” of his four-days (roundtrip) on the train. He examines “the degree to which [he] could write, research, teach, and perform other educational activities as if [he] were working at home or in [his] office on campus.” He finds that his train travel provided, for the most part, “a pleasant and productive environment for performing different parts of my work as a lecturer.” Lamb acknowledges his own privileged positionality—as a full-time, permanently employed academic at a well-resourced research institution where most of his teaching takes place online and asynchronously and in a part of the world with good train infrastructure—that allows him to engage in time-intensive travel and to rely on digital technology while doing so. For the most part, “these are issues of time and money,” he writes, “that apply to academic travel in general, rather than being specific to journeying by train.” In the end, Lamb hopes that what he has shared about his experience and reflections will lead others to see transcontinental train travel as a viable and sustainable option.

After Lamb talked about the first half of his trip during his presentation at the conference in Switzerland, several individuals who were in attendance later told him that they were eager to travel by transcontinental rail to future academic gatherings in Europe. His experience speaks to an article by Steve Westlake, Christina Demski, and Nick Pidgeon (“Leading by example from high-status individuals: exploring a crucial missing link in climate change mitigation,” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11, no. 1, 2024).

Behavioral change, especially by high-consuming individuals in wealthy societies, the trio of authors point out, has great potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions quickly. Among the most impactful changes are flying less, eating less meat, and driving less. Such voluntary changes, however, have proven elusive at scale, they note. Meanwhile, “governments have avoided introducing policies to limit high-carbon behaviours for fear of unpopularity and impinging on freedoms,” opting instead for technical solutions. Through a survey of 1,267 individuals in the United Kingdom, the authors explore the hypothesis that high-profile leaders—via a focus on politicians and celebrities concerned about climate change—could encourage low-carbon behavior were they to walk the (emissions reduction) talk. The trio point to three reasons for centering the behavior of leaders: 1) “their status gives them heightened power to shift societal discourse and social norms”; 2) they tend to have greater “lifestyle emissions” than most of their fellow citizens, which raises issues of equity and fairness; and, relatedly and arguably, 3) they have “more responsibility and power to guide society’s response to climate change.” Overall, the authors find a “strong desire” among the UK public for “behavioural leadership,” and for leaders to do the most in cutting their emissions. Consistent with this desire, they find that “leaders who lead by example with high-impact low-carbon behaviours prompt significantly greater willingness among UK citizens to adopt the same low carbon behaviours, compared to leaders who do not lead by example.” They also find that leaders who fail to practice what they preach will have a negative impact on the motivations of non-leaders to pursue low-carbon practices.

Academics, to varying extents, are also “leaders” who can and should help catalyze change by embodying low-carbon behavior. However, academics “feature prominently among frequent flyers,” write four transportation scholars. This is “because flying is deeply embedded in how the global academic system functions.” (See Jonas de Vos, Debbie Hopkins, Robin Hickman, and Tim Schwanen, “Tackling the Academic Air Travel Dependency. An Analysis of the (In)Consistency Between Academics’ Travel Behaviour and Their Attitudes,” Global Environmental Change 88, 2024: 102908.) This embeddedness helps explain the gap between academics’ professed concern (in general) towards the unsustainable nature of professional air travel and their actual practices. To provide further insight, the authors “cluster” academics based on diverse attitudes and practices, using a sample of 1,116 PhD students and teaching and research staff who work at University College London. The authors organize survey respondents into five clusters based on their responses to 17 statements and their levels of academic flying and the types of related activities (e.g., conference-going, fieldwork): conservative frequent flyers; progressive infrequent flyers; in-person conference avoiders; involuntary flyers; and traditional conference lovers. Overall, they find a modest link between attitudes toward flying and actual practices. They also find that “flying patterns of certain groups of academics”—particularly PhD students and full professors (who are disproportionately concentrated among the conservative frequent flyers, involuntary flyers, and the traditional conference-lovers)—“will not easily be altered.” As such, “universities as well as funding bodies, academic organisations and conference organisers should think carefully about policies discouraging conference-related flying.” Among the policies the authors recommend is a devaluing, by universities and funders, of in-person conference attendance (and international travel more broadly) in relation to academic promotions and grant funding. They also recommend shifting to virtual conference attendance, to less frequent conferences, and to regional and multi-hub conferences. Particularly for the conservative frequent flyers, charges for conference-related flying and carbon budgets should be explored. “In the end,” the authors contend, “it should not be international mobility, but mainly the advancement of knowledge enabling a more sustainable, healthy and equitable society that should lead to promotions for researchers.”

As suggested by the above-article’s recommendations, the type of conference (in-person versus virtual or hybrid, for example) has a large impact on a gathering’s emissions. It also informs who can attend and from where. A group of scholars investigate these matters in relation to conferences focusing on tuberculosis (TB) research. (See Kate Whitfield, Angela Ares Pita, Thale Jarvis, Shannon Weiman, and Teun Bousema, “Geographic Equity and Environmental Sustainability of Conference Models: Results of a Comparative Analysis,” The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Vol. 110, No. 5, 2024: 1039-1045.) They analyze five TB-related conferences—three exclusively in-person events, one fully virtual meeting, and one hybrid get-together—in order to “engage new audiences, rethink strategies for scientific exchange, and decrease the carbon footprint of in-person events.” In assessing carbon footprints, the authors analyze air travel, ground transportation, catering, and accommodations—as well the power consumed by servers, the network, and laptop computers. Not surprisingly (and consistent with other studies), they find that air travel accounted for 96 percent of CO2e emissions of the three in-person conferences. Attendance-wise, both the virtual and hybrid formats led to markedly higher numbers, while greatly increasing the number of participants from countries most burdened by TB; the enhanced diversity enriched the gatherings given the “wealth of insights and experience” researchers and practitioners from those countries bring. Meanwhile, the carbon footprint of the virtual conference was about 1,400 times less than the average of the three in-person events. Regarding the scientific quality of the gatherings, they find that “the virtual formats did not diminish the impact and dissemination of the science.” In concluding, the authors point to challenges associated with shifting to virtual events. They include the financial costs of producing high-quality virtual events (and what the appropriate fees for attendees should be) and the need for meaningful human interaction and networking opportunities. The authors thus encourage meeting organizers to experiment, engaging in a process of trialing and redesigning according to findings, conference mission and principles.

With more and more universities in Europe adopting carbon neutrality goals, there is a need to figure out how academic institutions “can work toward coherently enabling alternatives to flying with respect to all dimensions of sustainable development.” To do so, Nikki JJ Theeuwes, Shayan Shokrgozar, and Veronica Ahonenn (“Academic travel from above and below: Institutions, ideas, and interests shaping contemporary practices,” Energy Research & Social Science 119, 2025: 103890) examine two climate departments which are “among the most frequent flyers within academia”: the Centre for Climate and Energy Transformation at the University of Bergen in Norway, and the Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development at Utrecht University in The Netherlands. The scholars use a framework comprised of the 3Is—the “often conflicting institutions, ideas, and interests … [that] shape policy outputs and outcomes.” Via participant observation, analysis of travel policy documents, and interviews, the authors find that low-carbon forms of travel “are often not successfully integrated into academic travel policies and practices.” Rectifying this, the authors assert, “requires deep institutional, distributive, and ideological reflections on what constitutes ‘good science’”. Relatedly, it entails “a push for prioritizing long term sustainability over short-term efficiency … at the central level.” The authors offer various tools to enable institutions and individuals (with attention to their different needs) to both travel more sustainably and travel less.

As suggested previously on this website, the American Association of Geographers (AAG) is experimenting with various modes of conferencing with the goal of radically cutting the scholarly organization’s carbon emissions. For the AAG’s 2023 annual conference, this entailed various nodes, the biggest one of which took place in Montreal, Quebec. To open the node, Debbie Hopkins, of the University of Oxford, delivered a (virtual) keynote lecture for the AAG’s Climate Action Taskforce, to which three scholars responded.

Revised versions of these presentations were subsequently published as a special issues of ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies. In “Towards just geographies of academic mobilities,” (ACME, Vol. 23, no. 4, 2024: 281-292), Hopkins argues that what is at issue is not simply whether to move or not, but how and why we move, what this mobility performs, who has control over mobilities, and how they relate to gender, race, class and coloniality. In this regard, “the question of what just geographies of academic mobilities look like in the climate crisis is also one of what geography looks like.” Because what constitutes a just mobility needs to be contextual, positional, and thus multiple in terms of how it is manifest, the question necessitates “engagement with meta-frames and localized socio-spatial lived experiences of work/lives as academics in the climate crisis.” Farhana Sultana (“Just Academic Mobilities in an Unjust World,” ACME 23, no. 4, 2024: 293-295) deepens some of these insights through a focus on the intersection between practices of decolonization and decarbonization. Magdalena García (“Decarbonization and Decolonization of the Academy: A South-North Perspective,” ACME 23, no. 4, 2024: 296-298), similarly concerned about the ties between decolonization and decarbonization, explores various ways to democratize knowledge production. Jessica Dempsey (“Giving Form to Consciousness,”” ACME 23, no. 4, 2024: 299-301), then reflects on climate justice work at her own institution, the University of British Columbia, asserting the importance of linking efforts to reduce flying to other social justice concerns on campus. Finally, Patricia Martin and Joseph Nevins, in an essay inspired by the Montreal node (“Energizing Slow Scholarship: A Political Ecology Approach to a More Just Academy and Beyond,” ACME 23, no. 4, 2024: 302-309), examine literature on “slow scholarship,” finding little attention paid to energy consumption and mobility and their associated inequities. Slowing down, they contend, requires addressing the actual carbon-based materiality and speed of academic travel, thus providing the means to further the ethical and political concerns that underpin slow scholarship.

Speaking of slow scholarship and flying, sometimes we come across an article from a previous year that, regretfully, we overlooked, but that deserves our attention. Meredith Conti’s essay (“Slow Academic Travel: An Antidote to ‘Fly Over’ Scholarship in the Age of Climate Crisis,” Theatre Topics 31, no. 1, 2021: 17-29) is one. Within, the theater historian thoughtfully reflects on nearly a year of professional travel that she undertook without flying, finding “much to recommend in low-emissions transportation and the opportunities it affords the climate-conscious academic.” All of us, Conti suggests, are inevitably (and varyingly) complicit and compromised vis-à-vis the climate emergency, while rejecting the notion that “our individual actions are isolated and unwebbed from one another.” As such, each of us has responsibility, albeit different levels given “the profound inequalities imbedded in … the climate crisis,” to build a world beyond that dominated by fossil fuel. The scholar advances this analysis with a goal of challenging “the appropriateness of higher education’s enduring icon of success: the globetrotting, high-flying academic.”