In my last and final post for this series we will be exploring the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town, South Africa and their attempt to address earlier criticism through the exhibit “The Main Complaint.”

The Tufts Museum Studies Blog has previously written the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art (MOCAA) last year when Editor Kelsey Peterson addressed issues of diversity among the Museum’s staff. The privately funded art museum, often referred to as “Africa’s Tate Modern,” is the continent largest museum in the world dedicated to African art. In the two years since it’s grand opening the museum has faced many debates and controversies including the resignation of Executive Director and Chief Curator Mark Coetzee over allegations of racial and sexual misconduct and criticism regarding how accessible the museum is for the general public. MOCAA is in fact quite expensive at 190 rand approximately $14 USD. This may not seem exorbitant for museums in the U.S., but when compared to other costs in Cape Town, for example a Wagyu Steak Tartare dinner at a nearby posh waterfront restaurant is slightly less, it is an understandably unaffordable price for a city rife with economic and racial segregation.

From its onset, regardless of controversy, the museum has billed itself as an institution for all with a responsibility to represent everyone including audiences “who have often felt excluded from cultural institutions.” In fact, the opening exhibition, still on view today, entitled All Things Being Equal asks visitors to questions “How will I be represented in the museum?” On its website the museum makes it clear that representation is an ongoing process for the institution, answering the question of “Is the Museum an accurate portrayal and representation of the African Continent?” with this statement:

“This museum is at the start of a journey to participate in the conversation of what it means to be African, and then begin representing the continent. This will be a process over many years to fully understand and represent such a huge continent with so many traditions, languages and cultural groups. No collection can represent an entire continent but Zeitz MOCAA hopes its collection will make a significant impact on how Africa and the world view and has access to works of art from Africa and its Diaspora.”

As I found out on my recent visit to Zeitz MOCAA, the institution does its best work when it is being self-reflective through grappling with these thoughts and ideas of representation, accessibility and institutional power. These ideas are best represented in the exhibition The Main Complaint, which opened to the public in November of last year and will be closing at the end of this week.

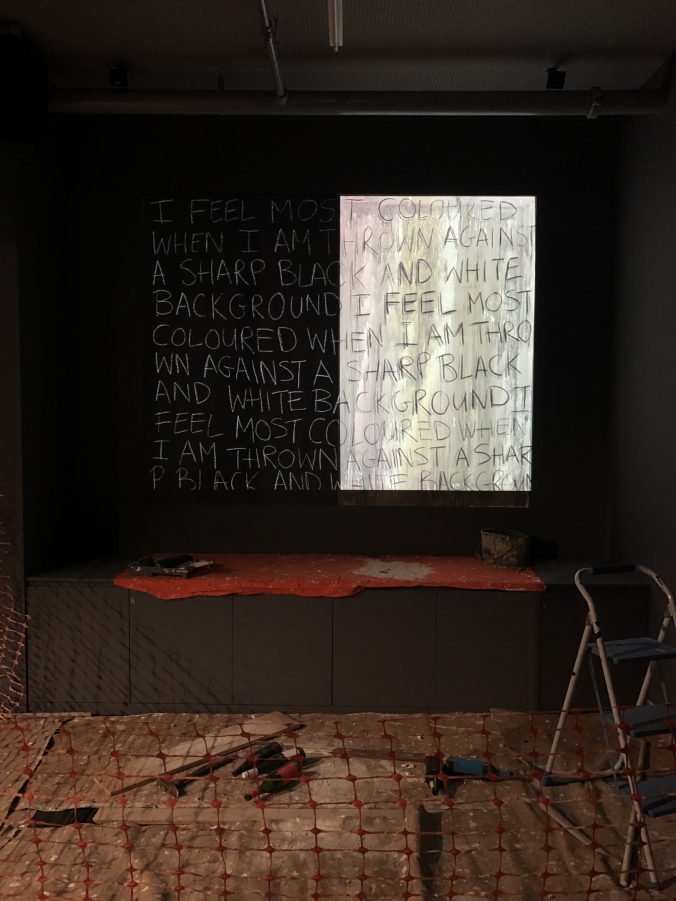

The Main Complaint is an infiltrating exhibition highlighting systematic, institutional failures, in an attempt to contextualise, recognise and repair. The exhibition exists as an ongoing series of interventions by museum staff and invited artists.

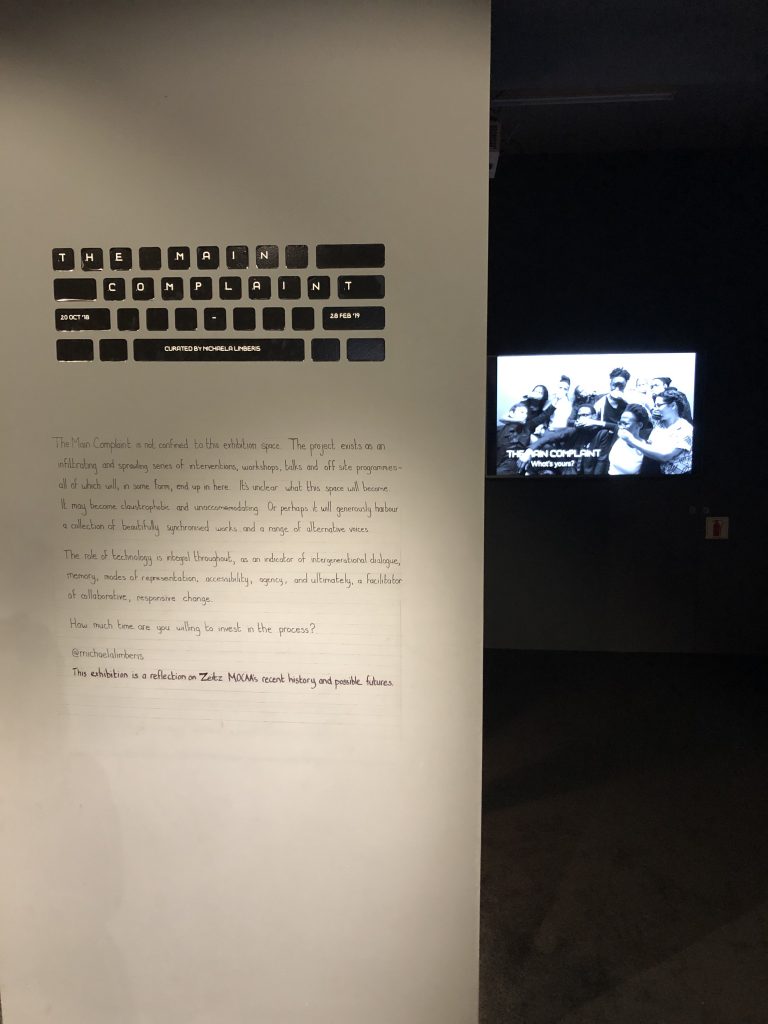

The Main Complaint is not confined to this exhibition space. The project exists as an infiltrating and sprawling series of interventions, workshops, talks and off-site programs – all of which will, in some form, end up in here. It’s unclear what this space will become. It may become claustrophobic and unaccommodating. Or perhaps it will generously harbour a collection of beautifully synchronised works and a range of alternative ideas.

The role of technology is an integral theme throughout, as an indicator of intergenerational communication, memory, modes of representation, accessibility, agency, and ultimately, a facilitator of collaborative, responsive change.

How much time are you willing to invest in the process?

According to Zeitz MOCAA Assistant Curator Michaela Limberis, the idea for The Main Complaint came from the idea of wanting to respond to the conversations surrounding the institution. The title is adapted from William Kentridge’s 1996 film, The History of the Main Complaint, which looks at white capital, power, and responsibility through the protagonist’s self-reflection while questioning what progress has been made. In an interview with ART AFRICA, Limberis described the importance of this exhibition for the young institution “some people perceived that there was a lack of communication between the museum and voices in the arts community, and believed that there wasn’t a sense of collaboration in the approach. As an institution that aims to be a representative of the African continent at large, there was an opportunity to being open to dialogue.” The artists explore many common themes of “access, value, representation, and ownership” within an institution.

The exhibition is in the in the Museum’s Centre for the Moving Image space, and as such relies heavily on film. Upon entering the space you are greeted by a foreboding security gate complete with a soundscape to set the scene. The piece, entitled “Right of Admission Reserved,” by Gaelen Pinnoch appropriately sets the tone for the rest of the exhibition. The piece is a physical barrier at the entrance to the exhibition space, access to which is only granted through pressing the “request access” button. The artists aim is to make viewers feel intimidated by the gate and/or the access control procedure. According to the label, the piece is an attempt to “distill the sense of exclusion, usually imparted by covert expressions of power, control or authoritarianism in the built environment, into something physical and explicit.” The work manifests into physical form the feelings many have towards cultural institutions. By having this piece at the entrance to the exhibition space, it helps to set the tone to complaints of access and power within cultural institutions.

Other works look directly at the relationships between artists and institutions such as Hhanya Mashabela’s “Ode to Institutional Critique” and Mitchel Messina’s “Lil Slugger Goes to Zeitz MOCAA.” Messina’s animated short was by far my favorite piece on view and made specifically for this exhibition. The film follows Lil Slugger to a slumber party at Zeitz MOCAA. From my understanding Lil Slugger represents smaller artists and the struggles they face while navigating institutions and systems of power. Throughout the film Lil Slugger is intimidated by security guards, rules, and other works of art before realizing that they may be struggling as well. The label description is written in Lil Slugger’s voice as he grapples with feeling hurt by “big systems’ while still trying to fix them:

And sometimes I wonder if these big systems broken and hurting also, and maybe they want to get better but only way how they can get attention is by acting out and doing things we wish they won’t.

If I ignore them maybe they will fall in with a bad crowd and get worse, maybe they will be pressured into being a badder system. But if I try to hug them they will push me away so hard I tumble and break my heart and never want to go back.

I was interested to see how many artists were willing to have their voices included in the exhibition and even more so in the institutions willingness to present narratives in which the Museum and cultural institutions as a whole were not always depicted in a positive light. I think overall Zeitz MOCAA excelled most in their exhibits that provided more self-reflective, meta looks at cultural institutions and the art world. I am curious to see how the Zeitz MOCAA will continue to progress with attempting to break down power structures and barriers to access and representation. As Limberis mentioned, as a young museum, Zeitz MOCAA has a lot of room for experimentation and that could bring the museum to the forefront as a leader in the museum world. I look forward to keeping an eye out for what they do next.

If you ever find yourself in Cape Town head to the V & A Waterfront for a visit to Zeitz MOCAA.