Step aside robins, unequal cellophane bees (Colletes inaequalis) are the true harbingers of spring in the eastern US. Bees emerge on the first warm day, often when snow is still on the ground, and they refuel on flowers after a long winter. And, they are already out in Boston: in 2022, cellophane bees emerged on March 16th!

Unequal cellophane bees are incredibly abundant, especially in suburban areas, so they are easily spotted around town. Before you head out to find them, read this blog, check out this video, and explore our field identification guide. After you enjoy your time with them, be sure to report photos to iNaturalist!

Flight Season

Unequal cellophane bees are active in very early spring, usually before trees have leafed out, and are active for four to five weeks. In Massachusetts, they are typically active from mid-March through mid-April.

Appearance

Unequal cellophane bees are small—like macaroni, about 0.75x the size of a honey bee—with “cute” heart-shaped faces, sand-colored hair, and bold bands on their abdomen. Males have long antennae and thick mustaches. Females are bigger than males, with cleaner faces, shorter antennae, and long hairs on their legs for carrying pollen.

Nesting habits

Unequal cellophane bees are easily spotted while nesting. Females build underground nests, excavating sand into a small mound at the surface called a tumulus (like an ant hill but with an entrance about the width of a pencil). They live in bee neighborhoods—termed aggregations—each of which can contain thousands of nests. In the first few weeks of the year, males can often be seen zooming low through the aggregation looking for mates.

Nesting aggregations typically appear on trampled, sandy south-facing slopes. Lakeshores, cemeteries, trampled picnic areas, sandy paths on the edge of the woods, and even backyards are all good places to look!

Similar Species

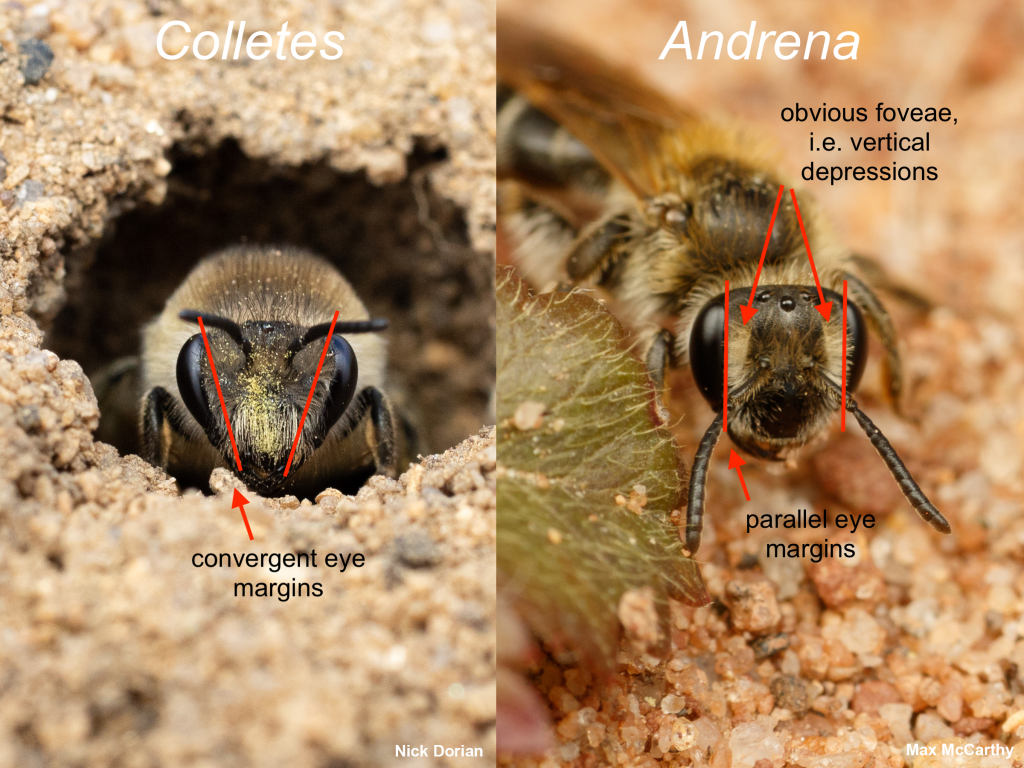

Cellophane bees Colletes can appear similar to many mining bees Andrena that also nest below ground. But, Andrena have obvious facial foveae and parallel eye margins, which Colletes do not.

Favorite Flowers

Unequal cellophane bees are not picky eaters. To attract them to your yard, plant spring-blooming trees like red maples Acer rubrum, apples Malus, eastern redbud Cercis canadensis, and serviceberry Amelanchier. They can also be spotted on garden bulb flowers like snowdrops, blue squill and crocuses.

Safety

You do not need to worry about being stung–cellophane bees are incredibly gentle! Even the biggest aggregations consisting of thousands of nests pose absolutely no threat to people or pets.