S1 E5 Supporting Students When Learning Feels Difficult

Episode 5 of CELT’s Teaching@Tufts: The Podcast takes on a challenge every instructor recognizes: how to help students persist when learning feels uncomfortable and hard. Hosts Heather Dwyer and Carie Cardamone explore why that difficult feeling matters, how it’s a signal of deep learning, and what instructors can do when students are tempted to disengage or offload the work to AI. Drawing on foundational learning science concepts like the zone of proximal development and desirable difficulties, they offer practical strategies including scaffolding, peer work, and opportunities for metacognitive reflection. The episode emphasizes a key takeaway: normalizing struggle as an essential part of learning helps students develop the persistence they need to build genuine expertise.

Strategies for Instructors

- Normalize the difficulty of learning to students: If it feels hard, that probably means you are learning something.

- Consider scaffolding the learning process for students: provide additional supports at the beginning such as checkpoints or structured learning opportunities, and then gradually take them away.

- Building opportunities for low-stakes peer work during class so that students aren’t struggling alone.

Resources & References

- Chapter 4: What Motivates Students to Learn in Ambrose, Susan A., et al. How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

- Dunning, David. “The Dunning–Kruger effect: On being ignorant of one’s own ignorance.” Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 44. Academic Press, 2011. 247-296.

- Bjork, Elizabeth L., and Robert A. Bjork. “Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning.” Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society 2.59-68 (2011): 56-64.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: the Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

This podcast was brought to you by Tufts Center for the Enhancement of Learning and Teaching and is hosted by Teaching at Tufts, https://sites.tufts.edu/teaching/

Music Attribution: Inspiring and Energetic by Universfield – License: Attribution 4.0

| [00:00:00] | *Music* |

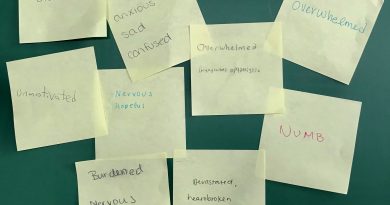

| Carie Cardamone [00:00:07] | Welcome to teaching at Tufts. The podcast brought to you by tufts, University Center for the enhancement of learning and teaching this season, in our first season, we’re exploring what the learning sciences can tell us about engaging today’s students, how their cognitive, emotional and social environments are changing, and what we as instructors can do to meet them where they are. I’m Carie Cardamone, and I’m here today with my co-host, Heather Dwyer. Today we’re going to talk about something we’ve all probably experienced, that feeling of uncomfortable difficulty that occurs when we’re engaged in a task of deep learning. We talked about this a little bit when we started talking about the impacts of AI on learning, because it is important to be able to be in that difficult place as we’re learning, that’s where learning is happening. And Heather recently ran a workshop on this topic. So, in preparing for that workshop, she dived into the literature, and she ran this workshop a couple of times, and had a chance to have this conversation with Tufts faculty and instructors. So, let’s start with, Heather, What made you decide to focus on this topic? |

| Heather Dwyer [00:01:13] | Yeah, I think part of it was the fact that it feels particularly salient in this moment because academic learning, it’s already a challenging thing, we’re asking students to do something difficult, which is to expand their thinking and to make mistakes. So that’s hard on its own, but they’re also managing a lot outside the classroom context. And I think this year felt particularly difficult for a lot of people. I think for many folks, it felt like a constant barrage of new and sometimes upsetting information. And so given the amount of cognitive load that I think students are managing all the time, it’s really important for us as instructors to think about how to help them persist in the learning process when it feels difficult. And I’ll also just mention this is not unique to students. Instructors experience this too, and so hopefully some of the strategies we talk about today will be maybe useful for those of us who are just managing that difficult feeling of deep learning and staying focused in daily life. |

| Carie Cardamone [00:02:15] | Yeah, that’s a really good point, Heather. I think we’re all dealing with a more distractible environment that’s being created around us in the world, the news cycle, the ways that we interact with the world. It’s always a pop up here “Oh, my God, you must pay attention to this thing”. Let’s think about it in the context of learning. You know, that’s what our series is about. And what does it look like when we’re encountering that hard feeling in learning in particular. |

| Heather Dwyer [00:02:42] | Yeah. So, we ask instructors about this, like, what do you in your daily life, as an expert in your discipline and in teaching your content? What do you do when you encounter that hard feeling? Instructors at this point are really practiced at this. They’ve they know and are familiar with that feeling, and so they had tools to handle it. They talked a little bit about breaking down a task into smaller chunks so that it’s a little bit more manageable. They mentioned sometimes they turn to a colleague for support, or sometimes they just kind of need to clear their mind, so they’ll kind of take a step back from the entire task and take a walk or go have a cup of tea or something. A lot of the instructors and myself included, recalled that difficult feeling as students and even acknowledged that, you know, we feel this on a day to day basis, even now in our work, it is very easy for those of us who are even familiar with that, that feeling to turn to distraction, such as checking email or looking at social media. |

| Carie Cardamone [00:03:42] | Yeah, it’s interesting. We’ve talked a lot about attention this season and this presents like disengagement, right? What you’re talking about, talking to your friend about something else, going for a walk. You know, there are other things people do, like drawing or sketching, all these different things that aren’t even rooted in something new in 2025. If we need to get back to that, I think it’s worth in this episode context, talking about, why, why should we not be disengaged? What is it that’s important about being in that necessary and uncomfortable space? Why does that matter for learning? |

| Heather Dwyer [00:04:20] | So I think for instructors, it can be helpful to think about sort of the space you want students to be occupying when you’re trying to engage them in the learning process. There’s this sort of happy medium in between, a space where it’s complete safety and comfort for a learner, where they’re completely capable of doing a task unsupported, right? That’s not the most productive place to be because they’re not being pushed to do new things, to learn new things, to apply new skills. They already know how to do that stuff, so there’s not a lot of new learning happening there. |

| Carie Cardamone [00:04:52] | That can also be kind of boring, if you think about it, like if you’re doing 50 problems that are the same in a math arithmetic class. By the time you hit the 30th you’re bored. |

| Heather Dwyer [00:05:02] | Yeah, that’s it’s true. Like, if you think about what is interesting for people when they’re doing a task, there has to be some level of challenge, otherwise they’re going to disengage with it, right? Like, if you think about doing a crossword puzzle or something, you want a challenge, right? You’re not going to do like, a super easy one. But on the other end of the spectrum, there’s the space of it being too difficult, where it would be difficult for a learner to do a task, even with the support that they need. And some might call this sort of the unsafe zone, or the panic zone, for the learner, that’s very demotivating for students too, because they don’t have any sense that they can accomplish the task. And so, where we want the students is to be right in the middle of those two ends of the spectrum. And it’s a space where there’s productive learning happening, but it’s pushing us, and that push doesn’t always feel easy or comfortable. It can sometimes feel really hard, and it can feel actually quite uncomfortable, but this is the space where we want our students, because that’s where students can maybe do a task, but only with the guidance and feedback and encouragement from the instructor. Right? For those of you who are interested, there’s a name for that space. It’s called the zone of proximal development. It was developed by a foundational educational psychologist, Vygotsky, and we can drop some resources about that in the show notes, if it’s helpful. |

| Carie Cardamone [00:06:23] | Yeah, no, that’s really interesting. And it also resonates with me about why the learning sciences are so durable. Some of these theories in education started centuries ago or decades ago, in Vygotsky’s case, but like, they persist through because there is a nugget in there that that’s really important, right? And so being in this particularly learning edge, or zone of proximal development challenge zone, is where the learning is really happening. What does it look like when we’re in that challenge zone? That doesn’t feel very good to be there, but we’re persisting through it. |

| Heather Dwyer [00:06:59] | If we’re not ready to persist, like if the student isn’t able to do that, what we might see in a classroom is disengagement, students giving up, turning to distractions or turning to tools, like AI, to delegate their tasks, in part because the student may feel like they can’t do it. They may not believe that they can achieve the task. And this actually happens to me all the time. I’ve noticed for myself my attention span has gotten shorter over time. I also do incorporate generative AI into my daily workflow, and so it’s very tempting to go there, but I’ve found that if I’m trying something and it’s not working out for me, I will pop over to other easier tasks, or I’ll start thinking about something completely unrelated, like what I need to buy at the grocery store. And so, we want to move students away from that temptation and toward persisting with a task even when it feels difficult. And I mentioned a little bit the importance of students feeling or believing like they can achieve something. I think that’s a really important part of this equation, because it’s related to the idea that students need to believe that they can achieve a task in order to feel motivated enough to persist with it. And so, we can think a little bit about how to create a supportive and learning environment where they feel like they can actually achieve something. |

| Carie Cardamone [00:08:17] | Yeah, which you’re talking about is making me remember, when I was working on my PhD dissertation. How you be in these moments where you really didn’t believe you could accomplish this task. It was really hard, and you needed to find a way to persist through it. When I was a student, some of the things that I did were like, go swim for 45 minutes and doing laps in the pool. You’d take your mind off of it, but you’d still keep coming back to why can’t I figure out how to do this thing, and then you’d come back to it refreshed with new ideas, and be able to persist in going and that motivational piece, I think, is critical, believing that there is a way through that it’s worth it, caring enough to not give up and keep persisting it. What are some of the concrete strategies that you know, instructors can think about building into an environment for students to encounter. |

| Heather Dwyer [00:9:04] | So, as I was developing this workshop, I came up with a couple one has to do with this idea of helping students develop the belief that they can actually achieve a task, and one way to do that is through the idea of scaffolding. Many of you may have heard of this concept before, but the idea is just to provide structures to your course or to an assignment, so that students have a support system as they are building up their knowledge and their skills, and then as students get a little bit stronger as they gain that expertise and that mastery, you can take that scaffolding away. But one example of what this might look like is if you have final project that you want students to do, you might break it down into smaller tasks and set up like milestones that the students have to achieve along a certain timeline. So not only does that make the task more manageable, but it also allows them an opportunity for early success. US, which, again, can be very motivating for students. You can provide them with a smaller thing that’s achievable. You can give them positive feedback and reinforcement, and that helps them with that belief that they can actually accomplish what it is you’re asking them to. So that’s one, scaffolding. |

| Carie Cardamone [00:10:16] | I appreciate that. That’s also something that you said the instructors brought up when you ask them, you know, you as an academic, how do you accomplish big things that feel overwhelming or really hard, you start by breaking it up into little tasks where you chart your path through it. And this is sort of like giving that roadmap to the students, that pathway through. |

| Heather Dwyer [00:10:35] | Absolutely it’s a life skill. Another strategy that I would share is to incorporate peer work when possible. It doesn’t have to be formal. It can be really; it can be brief. It can be done in five minutes in class, but giving students the chance to work together a little bit, not just so that they’re exercising their skills and collaboration, but really so that they can see they’re not alone in their struggles, and it helps kind of normalize those feelings of confusion and reduces the sense of isolation that can happen there. |

| Carie Cardamone [00:11:06] | That’s a really important one. It leverages social learning too. And I think, you know, maybe in a future episode, we should talk about, you know, groups and learning together. Because I think that’s a huge bonus. Like, why are you in a college class and not just signing up to Duolingo to learn something, right? And that it’s that environment that you get the instructors, the TAs and the peers in the classroom. |

| Heather Dwyer [00:11:28] | Yes, absolutely. And then a third strategy that I’ll share came from a student. I asked a student, what would you like to see instructors do in terms of supporting students through that feeling of difficulty when they’re learning new things. And this student shared that instructors would emphasize depth over breadth in their courses. And so, she shared an example about reading assignments and reading load, and a situation she had found herself in where the reading load was quite high in volume, but also each reading was really dense and deep, and so she felt compelled to understand in depth each reading, but it was very difficult for her and therefore demotivating. And so, she suggested that one way to address this is to pull back a little bit on the volume, but to maintain that emphasis on depth, because then students feel more motivated to stick with it when it starts to feel hard, rather than turning to just sort of a superficial surface level understanding of volume of content of reading. |

| Carie Cardamone [00:12:31] | That makes a lot of sense. Yeah, you really feel that satisfaction when you really immersed yourself and wrapped yourself in something and persisted through it. You know, it strikes me that something really important to being able to persist through it is understanding where you are, like, you have to be a good judgment of when you’re actually learning and when you’re just spinning your wheels. We’ve all had that experience where a student comes to you and they said, I spent 10 hours reading this one chapter in this textbook, and you’re like, “Hmm, maybe that wasn’t that good”. Maybe you weren’t learning when you were doing that. What were you doing when you were doing that? And you know, cognitive scientists like to call this metacognition, this awareness of your learning. Can you expand on this concept a little bit? |

| Heather Dwyer [00:13:12] | Yeah, so folks listening may be aware that humans just are not always very good judgments of what we know or when we’re doing very well at learning, and often our emotion or our feelings can cloud our judgment of what we know. So, you may have heard of the Dunning Kruger effect. This is what happens when people tend to overestimate their competency, especially when their competency is a little bit on the lower side. And not only are we not really very good at judging our performance when we’re novices, which our students are there, they’re novices, but we’re not always very good judges of when we’re learning effectively. And what happens is when we encounter that difficult, uncomfortable feeling, it doesn’t feel like we’re learning, it just feels really hard, right? And so, it feels easy to turn away from that, that situation. So, one way to address this as an instructor is to try to incorporate this idea of desirable difficulties. And what that really means is making it feel difficult in a way that is productive and engaging and good for learning desirable difficulty strategies really prompt students to encounter the hard feeling that results in more durable learning. And I’ll just pull a simple example, which comes from one of our earlier episodes about retrieval practice. So, if you listen to one of our earlier episodes, we talked a little bit about the importance of retrieval practice, which is the idea that you’re sort of testing yourself as a learner and making sure that you’re able to retrieve on your own whatever knowledge and skills you need in the moment. And testing oneself feels harder and less comfortable than, say, rereading the notes. It can be very tempting to when studying for a test, to just go back and reread your notes, but testing oneself is a lot more effective so retrieval practice. This is a great example of a desirable difficulty. And then coming back to this idea of the Dunning Kruger effect, where we’re not very good judges of what we know, particularly if we’re novice like our students are, I would encourage folks to think about incorporating exercises or opportunities where students can see for themselves, where they stand in their learning, and to make that as low stakes as possible. So if you were to give a student, say, an ungraded practice test and have them do it and then reflect on their performance, that can help the students see with their own eyes where they already have expertise, and you know where there are some gaps, and what they need to do to address those gaps. |

| Carie Cardamone [00:15:43] | This is reminding me of all the ideas around knowledge surveys and asking students, how well do you think you know something, and then giving them a question and letting them try to wrestle with it, and then they get to see for themselves, how well, how accurately did they judge whether or not they knew this concept when they actually tried to apply it. So today we’ve talked about finding that learning edge, that place where learning is most productive, but it feels hard, and it maybe doesn’t feel so good. And we talked about some strategies of that instructors can pull out, such as scaffolding peer work, or even just giving students the space to go deep in a particular topic, to get over it. When you think about today’s conversation, or really the workshop, is there one takeaway that you want instructors to be thinking about in terms of supporting students through the difficult learning? |

| Heather Dwyer [00:16:34] | Yeah, I touched upon this a little bit when we talked about the importance of peer work. But I would say that it would be really good if instructors could just normalize the difficulty of learning to students. Learning is meant to be hard. It’s meant to feel hard, and only repeated practice can get one over that feeling and get somebody to actually be good at what it is that they’re attempting. And I struggle with this all the time with my daughter, who’s learning how to play the piano. She’s seven years old, and she is encountering this uncomfortable, difficult feeling all the time, and she’s she gets very frustrated, and I try to tell her that that feeling means she’s learning, and that it’s okay to feel that way, and it’s normal to feel like that, and it’s part of learning and to just try to as much as she can get used to that feeling, but it’s really hard. And I especially feel for today’s learners, because they have so many distractions available to them, and they also have many ways to offload tasks, particularly with generative AI at our fingertips. And so, I think as much as faculty can just normalize this feeling of challenge and building opportunities to practice encountering it and to be comfortable with it as much as possible. I think that can be really helpful. |

| Carie Cardamone [00:17:49] | Thank you, Heather. I think that’s a great takeaway. So today, we really talked about why learning feels so hard, how we occupy that space where learning is difficult. And I want to thank everyone for joining us today. The resources referenced today in the episode can be found in the show notes. “How Learning Works” is available in the CELT lending library, and of course, you can always reach out to celt@tufts.edu if you have any questions about incorporating these activities into your class. Until next time, keep teaching, keep learning, and don’t forget to take care of yourself too. |

| [00:18:20] | *Outro Music* |