“5 Quick Questions for AEI scholar Chris Miller on the geopolitics and economics of semiconductors” – James Pethokoukis

With Chris Miller, Associate Professor of International History at The Fletcher School

The creation of the microchip is at the center of many themes that appear in this newsletter: the unplanned (and not easily replicated) rise of Silicon Valley, the economic gains ushered in by the ubiquity of computers, and the possibility of an AI productivity surge in the coming years, to name a few. But semiconductors also play a key role in today’s debates about industrial policy, government technology strategy, and national security. A new book says this about the importance of the chips that power our devices: “[S]emiconductors have defined the world we live in, determining the shape of international politics, the structure of the world economy, and the balance of military power.” Here’s my 5QQ with the author.

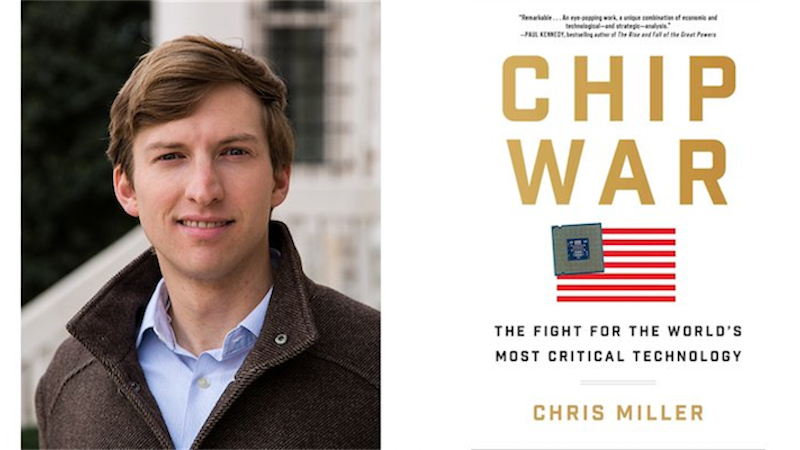

Chris Miller is a Jeane Kirkpatrick Visiting Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and author of the new book, Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology.

1/ As the US looks to stay competitive in the chip space, what lessons should we draw from the history of the development of the microchip?

Today, all manner of devices depend on chips, from microwaves to automobiles to smartphones. Chips have spread across the economy, providing computing power to these devices, only because it has been economically viable to do so. Scientific advances alone weren’t enough to turn an invention into a society-transforming technology. It was only because companies were able to find profitable businesses manufacturing chips by the millions that they’ve had such a transformative impact. Government can play a role in funding science and technology development, but it takes companies to scale technologies and distribute them across society.

2/ In your book you argue that geopolitically microchips have become the new oil. How does that illustration help us understand the importance of chips? What are the limitations of that analogy?

Oil is often considered a “strategic” commodity because a small number of countries can, if they choose to cut supply, drive up oil prices and exert a major impact on other countries’ economies. Saudi Arabia is the best example — the Saudis have used this capability repeatedly for political aims. The chip industry is no less important than oil to the functioning of modern economies, but production is even more concentrated. Taiwan, for example, produces over a third of the new computing power the world consumes each year — a far greater market share than the Saudis have in oil.

3/ To what extent should we view the coming “chip war” between the US and China as a competition between state planning and market capitalism?

The US-China chip war is partly a competition between state planning and market capitalism. But its more complex than this. China has managed to adapt some market mechanisms in its state planning system, which has helped it avoid some of the worst errors of Soviet-style state socialism. On top of this, Chinese firms often compete in the same global markets as Western market-oriented firms, but they have access to highly subsidized capital investment whereas Western firms don’t. So in many ways it is an uneven playing field between Chinese and Western firms.

4/ What principles should guide policymakers in Washington as they craft policy to further our chip-making capacity?

I think there is a strong national security rationale to reducing our reliance on chipmaking capacity in geopolitical hotspots in East Asia, above all, in Taiwan. This isn’t about economic efficiency, this is about preparing for a potential crisis. Given that 90 percent of the world’s most advanced processor chips are produced in Taiwan, we have little margin for error in beginning to prepare.

5/ Why does Taiwan have such an edge in chipmaking? How can we learn from their success?

Taiwan’s biggest chip firm, TSMC, has grown to become the world’s biggest chipmaker for several reasons. First, it was founded with an innovative business model. Before its founding, almost all companies designed and manufactured their chips in house. TSMC aimed only to manufacture chips, allowing other companies to specialize in design. This let TSMC acquire a large array of customers and fabricate far more chips than competitors, producing dramatic economies of scale. In addition, TSMC benefitted from a supportive government, which provided generous tax incentives for investment — a crucial factor in such a capital intensive industry. Finally, TSMC executed flawlessly on its business, earning a reputation for excellent customer service alongside top-notch technology. TSMC’s rise is a reminder that tech companies’ fate doesn’t only depend on having the best technology, but also the best business model.

This piece is republished from Faster, Please!