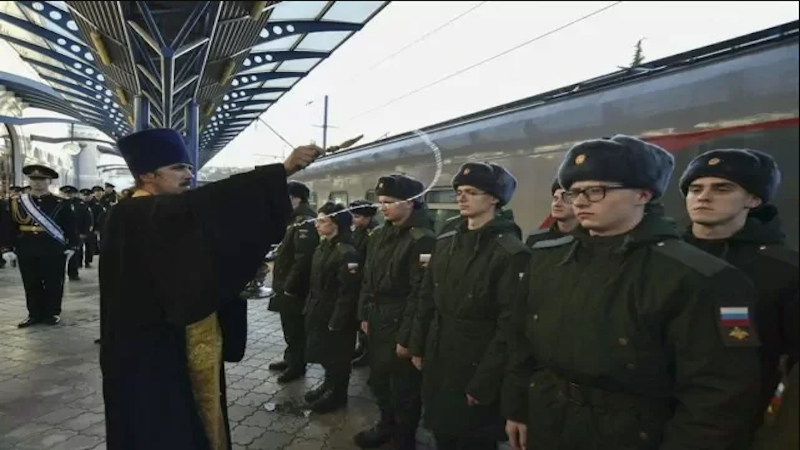

A ‘Revolution’ in Military Recruitment for Russia

By Pavel Luzin, Visiting Scholar of the Russia and Eurasia Program at The Fletcher School

On April 11, the Russian parliament passed a draft law that can be considered a “revolution” in the way Moscow conducts recruitment for the Russian Armed Forces (Sozd.duma.gov.ru, April 11). This measure was passed even before the other draft law on increasing the age of conscription, which was introduced into parliament a month earlier (Sozd.duma.gov.ru, March 13). The legislative rush on this legal matter is rather unusual: Despite the fact that the original version of the adopted draft law was introduced into the State Duma as early as 2018, the amendments to it meant an almost complete revision of the original version and appeared just several hours before the official vote was held (Meduza, April 12).

A number of key specifics were included in the draft law. To begin with, the Kremlin finally decided to increase the level of coercion and even intimidation in an aim to limit Russian male citizens’ opportunities to avoid either conscription or mobilization as much as possible (Sozd.duma.gov.ru, April 11). Now, draft summons may be sent electronically, and the military authorities do not even need confirmation of receipt from those who will be conscripted.

Moreover, the whole recruitment system will be based on a massive, centralized electronic database, which, in theory, will aggregate and combine all the personal information about any single recruit from the databases of other government institutions and even employers. And if recruits miss or ignore the draft summons, their rights are planned to be limited significantly: they will immediately lose the opportunity to travel abroad (and probably within Russia if it concerns airlines and railways), and they will not be able to register a private entity, complete real estate transactions, receive bank loans—and, in some cases, they may even be prevented from using their driver’s licenses freely (Sozd.duma.gov.ru, April 11).

Nevertheless, it is unclear whether such an electronic recruitment system is even possible considering the massive amount of fragmented and non-standardized information in many government institutions and the low level of inter-agency coordination among them.

Furthermore, the draft law will realize the approach in which a conscripted soldier is allowed to sign a contract for military service from the very first day of service, regardless of education level (Sozd.duma.gov.ru, April 11). Together with the planned increase of the conscription age range from 18–26 to 21–29, this will create a paradoxical situation if contracted military service is still possible at the age of 18, well before someone could be drafted.

Several reasons explain Moscow’s rush with the new recruiting system. It confirms that the Russian leadership is facing challenges with conscription. In this way, the spring and fall conscription campaigns of 2022 had a plan to recruit 134,500 and 120,000 conscripts, respectively. However, the actual number of soldiers drafted from April to July 2022 hardly achieved 90,000, and the conscription plan from November to December 2022 also likely did not reach its goal (Zvezdaweekly.ru, July 12, 2022; see EDM, December 5, 2022). Moreover, considering the fact that most contracted soldiers in the Russian Armed Forces are recruited from drafted soldiers during their one-year term of service and that the war against Ukraine has undermined the overall popularity of military service, the number of recruited contracted soldiers will almost assuredly be much lower than before.

The ongoing spring conscription campaign started on April 1 and has a plan to call up 147,000 recruits, more than any time since 2012 (Base.garant.ru, March 30). And even the first week of conscription demonstrated a negative dynamic exacerbating the increasingly dire situation with the rotation of manpower in the Russian Armed Forces amid the ongoing war. Therefore, the Russian authorities are trying to increase political and administrative pressure on potential recruits, even intimidating them with a promise of unavoidable military service. The goals here are: to force young Russian men to opt for a “better sooner than later” approach to conscription and thus make the most of those who are subjected to conscription in trying to convince them to commit to contracted military service.

Other major reasons for rushing the draft law involve the troubles with the “partial mobilization” that started in September 2022 and has yet to be ended officially. The Kremlin realized that it cannot precisely pinpoint where most male citizens subject to military service are located. The problem here is that Russian military recruitment depends on the systems of formal residency registration and military registration at places of work and personal residences. All these systems worked relatively well during the Soviet era. However, when tens of millions of Russians live outside areas of formal residency registration, do not register themselves at military recruiting offices near their homes and their employers do not conduct military registration at their workplaces, the authorities’ capacity for recruiting and mobilizing soldiers decreases dramatically (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, March 25). And thus, the Kremlin is trying to fix this problem by the technical but still authoritarian measure of creating the centralized database for recruitment.

Even Moscow’s attempts to recruit volunteer soldiers into the recently created irregular volunteer units by using short-term contracts (starting from three months) instead of the two- and three-year contracts typical for the Russian Armed Forces and further mobilization also do not appear to be attractive in the eyes of Russian society (Pnp.ru, March 18). Consequently, the proclaimed digitalization and automation of the recruiting process is aimed to restore the Kremlin’s control over the remaining potential manpower.

Ultimately, perhaps one more key reason explains the ongoing “revolution” of the military recruitment system in Russia: the Kremlin feels that it is losing control of the war against Ukraine as well as the wider domestic political situation. Even so, the economic consequences of the draft law are evident: a demoralized Russian society will not respond kindly when the authorities permanently threaten them with recruitment and mobilization and will not invest in the country as a result. Thus, the shadow economy as a main measure of resistance will likely increase in its influence—and further damage the Russian economy.

(This post is republished from The Jamestown Foundation.)