Amendments to Russia’s Constitution as a step toward the war in Ukraine

By Stanislav Stanskikh, Visiting Scholar at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy

On January 15, 2020, Russian autocrat Vladimir Putin unexpectedly created a detailed plan to change the country’s Constitution. These changes were rightly characterized as a “special operation,” a nod to Putin’s KGB background. During the discussion and adoption of Putin’s amendments to the Constitution, various explanations for the unexpected initiative began to appear: from Putin’s illness and the need to get rid of the “lame duck” syndrome, to the desire to avoid paying colossal compensation awarded by the European Court of Human Rights to the shareholders of the “squeezed out” oil company Yukos. The explanation of the amendments as preparations for full-scale war was viewed as almost unbelievable and therefore was not even considered.

Russia’s perfidious attack against its neighboring state – Ukraine – during the early hours of February 24, 2022, similar in style to Nazi Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in the morning of 1941, allowed us to take a fresh look at the reasons for the political and legal processes initiated by Putin on the eve of the war, including amendments to the Russian Constitution.

By 2019, Russia was already an authoritarian state, “in which the regime seeks to legitimize its rule through managed elections, populist appeals, a foreign policy focused on enhancing the country’s geopolitical influence, and commodity-based economic growth” with the dominance of one political force and the systematic persecution of dissidents. Like many other legalistic autocrats, Putin’s personalist political regime has sought to give a veneer of legality and legitimacy to its criminal decisions by using formal norms and institutions. This approach is rooted in the Soviet legal education of Putin and his closest associate, Dmitry Medvedev. For decades, Soviet legal culture did not recognize the principle of constitutionality. Instead of constitutionality, the principle of legality and formal compliance with the black letter law rather than its spirit was observed.

In contrast to the Soviet era, when the Constitution was not a normative document of direct action and could not be applied in court and law enforcement practice, Putin came to power during an ongoing experiment in democratic transition in which the Constitution played an important role.

Taking advantage of a constitution that favors presidential powers, Putin carried out a series of anti-democratic changes that finally destroyed the already weak system of checks and balances. Most of his so-called reforms were carried out without outward contradiction to the Constitution and even with formal reliance on it. For example, it is possible to recall the creation of federal districts in 2000, which were not provided for by the Constitution, or the reform of the procedure for the formation of the gubernatorial corps and the Federation Council in 2004, recognized by the Constitutional Court as constitutional.

When the Constitution ceased to meet new political realities, the first amendments were made in 2008, which increased the presidential term from four to six years and the parliamentary term from four to five years. Further amendments in 2014 abolished the Supreme Arbitration Court and, with the sanction of the Constitutional Court, legitimized the annexation of Crimea.

After the 2011 protests against large-scale fraud in the parliamentary elections and presidential castling, Putin’s political regime, for the first time, initiated systemic political repression against dissidents based upon formal reliance on the Constitution and legislation.

Having annexed part of the territory of Ukraine, unleashing an armed conflict in Eastern Ukraine and moving to a new stage of political repression in the absence of political pluralism, the Russian political regime finally took shape as an authoritarian one in 2014-2015. As one journalist righteously pointed out in 2017, “For Putin and his new Russia, […] the time for political – and military – expansion has just begun. Now, Russia thinks of itself as the reincarnation of its own past. And it will act accordingly.”

After the possibility of a diplomatic settlement to the armed conflict in Eastern Ukraine by 2019 had been exhausted, the Kremlin began to look for other options for resolving the Ukrainian Question, which demanded from the Kremlin the stability of an authoritarian political course. This stability was threatened not only by ending the Crimean consensus, but also by the Constitution, which prevented Putin from running for president in 2024 and formally guaranteed political freedoms and universally recognized principles and norms of international law.

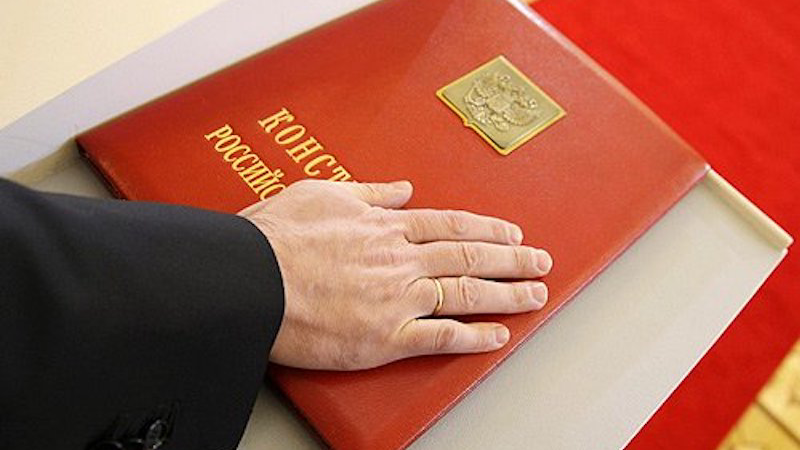

In January 2020, Putin initiated large-scale amendments to the Constitution, as well as an extraconstitutional procedure for their adoption, including a nationwide vote. The amendments to the Constitution were adopted in violation of the existing constitutional procedure, but nonetheless, were recognized by the Russian Constitutional Court as fully in line with the Constitution. This initiative provoked an extremely negative reaction from Russian civil society, human rights activists, the democratic opposition, experts, and the international legal community.

These amendments and the procedure for their adoption gave Putin carte blanche to carry out further political repression, further solidify his power, and adopt more unpopular reforms.

The symbiosis of authoritarian practices, nationalism, and right-wing conservative ideology has reinforced the Kremlin’s militaristic ambitions. A year after the adoption of amendments to the Constitution, Russia, as an aggressor nation, with the participation of authoritarian Belarus, began to gather troops to the border of Ukraine and, on February 24, 2022, treacherously attacked its neighboring state.

A full-scale military invasion, which was not crowned with lightning success, led to new challenges to the stability of Putin’s political regime, “whose authoritarian and nationalistic approach had some features in common with fascism”, jeopardizing its existence. To effectively address these problems, the Kremlin began to look for other sources to maintain political stability and destroy political opposition in Russia. This included brutally suppressing anti-war and anti-government protests, withdrawing from the jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights, introducing war censorship, annexing new Ukrainian territories, and taking other steps similar to the experience of Nazi Germany and Stalin’s USSR.

The presence of new faithful allies of the Kremlin, such as the wounded Constitution and the obedient Constitutional Court, has led to an atmosphere of permissiveness. This allowed the Russian political circles not only to usurp power and fight against dissidents but also to commit war crimes and crimes against humanity in Ukraine, which are already well-known and documented by the international community.

It is obvious that the discredited Constitution, which finally turned into an imitation legal tool, must be replaced with a new one. In 1993, the United States and other Western countries supported Boris Yeltsin’s coup d’état and recognized the legitimacy of the “broken” Constitution, which failed to guarantee a democratic transition. Hopefully, next time, Russians will find a better path to democracy with the assistance of the West, so all actors will be guided by the values of the rule of law and not by considerations of short-term political expediency.

This post was republished from The Fletcher Forum.