American Foreign Fighters in Ukraine

Lark Escobar, MALD 2022 Candidate, The Fletcher School

Predictions of the imminent Russian invasion of Ukraine began floating around the veterans’ networks in mid-February 2022. Veterans were already engaged in the overwhelming task of Afghan evacuations, though there was a pause in exfiltration flights due to Taliban threats, so the lull in tempo created the perfect sweet spot for turning attention towards Ukraine. In the first 48 hours of Russia’s invasion, many handlers from the Afghan evacuations operations sprung into action; they began preparing their kits and supplies to head to Poland to help crowdsource evacuations of Americans and retired NATO personnel from Ukraine while simultaneously ramping up medical supply runs.

These seasoned individuals, experienced with humanitarian response and disaster relief, were not the only actors in the landscape. American military veterans outside the constellation of NGOs working on Afghan evacuations took an interest in the cause, as well as unprepared civilians who were excited to engage in violence began flooding into the area on private commercial flights to Poland and neighboring states.

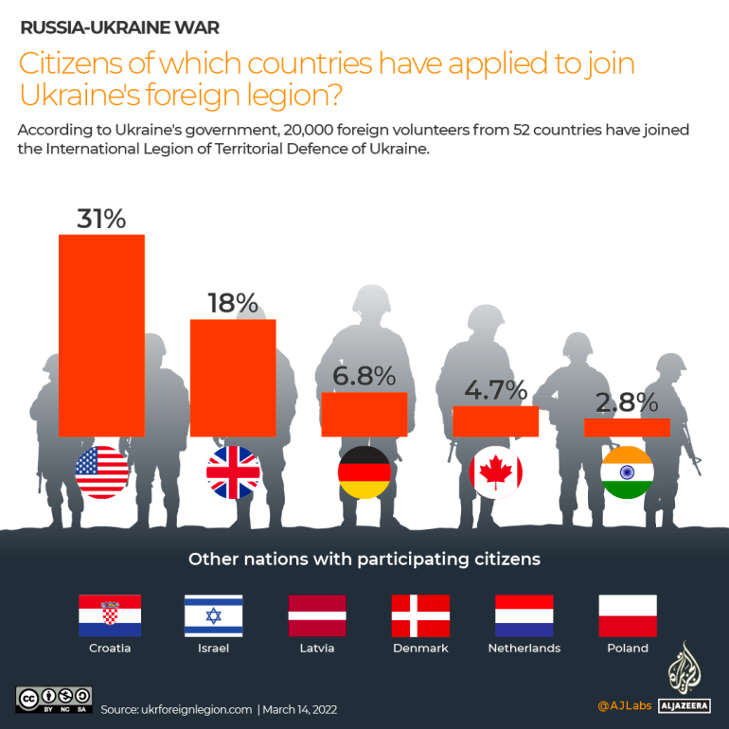

In the absence of ground support from NATO, Zelenskyy called for foreign fighters to join the Ukrainian armed forces, which began waves of interest from Americans, the Israeli Defense Forces, Germans, Brits, Canadians, Dutch, Danes, and Poles, among others. The steps for joining up seemed simple enough, though the US Department of State made it clear that Americans were not to travel to Ukraine and would not be evacuated by the government if they faced an emergency there.

While the idea of an ad-hoc foreign legion sounds like a great idea in theory, in reality, things have not gone smoothly on the ground. Volunteers are not issued weapons or requisite protective gear and may be sent on dangerous, difficult tasks because they are unable to integrate into existing Ukrainian units seamlessly. Interoperability requires having actual combat skills and experience gained through joint training exercises, adequate language skills, and equipment, all of which are missing in the calculus of volunteering to fight.

Thus, the American and British volunteer fighters are left waiting to be put on the battlefields and are waiting in the winter cold without food supplies– or they are sent on high-risk missions. They also face a questionable legal status if the Russian military captures them since mercenaries do not enjoy the same protections under the Geneva Conventions as official combatants. Captured foreign fighters are not automatically eligible for prisoner of war status.

Assuming the foreign fighters do return home unscathed, they may face court-martials or other legal battles. In the calculus of the war, the foreign fighters’ net impact may be neutral– at best and at worst, result in unnecessary loss of life. Although there are no clear tallies of foreign fighter losses and casualties yet, the thousands of volunteers may be gambling with their lives without making the helpful impact they intended to have.