The Strategic Upside Behind Russia’s $55 Billion ‘Power Of Siberia’ Pipeline To China

By Ariel Cohen, Alum of The Fletcher School at Tufts University

December 2nd was a notable day in the strategic relationship between Beijing and Moscow, which saw the first shipments of Russian natural gas to China via the much-awaited Power of Siberia pipeline. The $55 billion project is Russia’s most significant energy undertaking since the collapse of the Soviet Union, part of a larger $400 billion deal to supply China with 38 billion cubic meters of natural gas (bcm) per year for 30 years.

Pressure from Western sanctions – brought on by Russia’s illegal 2014 annexation of Crimea – is accelerating the Kremlin’s pivot away from the European Union towards the energy hungry East.

The 1,800 mile pipeline is a hedge against a potentially shrinking market in Europe, where souring diplomatic relations and rapid penetration of renewables threatens the appetite for Russia’s oil and natural gas in the long-run.

As the Power of Siberia sends its first molecules of natural gas to China, Moscow is also in the midst of launching two other landmark energy projects — the Nord Steam 2 undersea Baltic gas pipeline to Germany and the TurkStream pipeline to Turkey and Southern Europe. Together these initiatives show a strategic effort by Russia to limit gas transit through Ukraine and diversify its customer base.

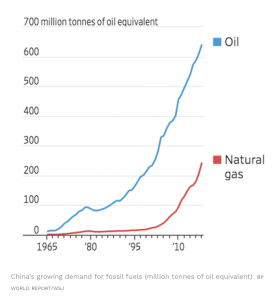

Russia is home to the largest reserves of natural gas on the planet — 20% of the global total — while China is the world’s largest energy importer. By positioning itself between European markets to the West, and the rapidly growing gas-hungry Chinese markets to the East, Russia is preparing to take advantage of arbitrage opportunities. The geo-economic leverage that comes with a new energy pipeline is also not lost on Russia – the Kremlin knows how to use natural gas exports as a foreign policy weapon.

But the Power of Siberia project, much like Russia’s strategic position vis-à-vis China, may not be as strong as it seems.

On the surface, optics are good. Chinese President Xi Jinping has described Russia’s Vladimir Putin as his “best friend” and declared that “Russian-Chinese relations have reached an unprecedented level.”

The two leaders are galvanized by what they consider an unhinged United States, and a belief that together they can create an alternative to the Western-led global order. The U.S. – China trade war, Western condemnation of China’s actions in Hong Kong, and continuing sanctions against Russia are reason enough for Putin and Xi to start their own axis.

Yet all is not rosy in this blossoming romance. China, whose economy is eight times larger than Russia’s, and is increasingly technologically more advanced, is the senior partner in the tandem. Russia is approaching its subordinate role with mixed feelings, on one hand realizing the power disparity, but on the other hopeful that it can benefit from closer ties to the world’s most dynamic economy.

Like the Russia-China relationship, the reality of Power of Siberia project may be less positive than advertised. Mikhail Krutikhin, from the Carnegie Moscow Center, succinctly stated:

In a nutshell, the “Power of Siberia” is a very costly window dressing. For the global market, this project gives nothing…Until 2030, the Power of Siberia will not even pay off.

Because Russia will compete against other pipelinessupplying gas to China, including from Turkmenistan and Myanmar, as well as against shipments of sea-borne liquefied natural gas (LNG), China is in a favorable bargaining position. Contract details have not been made public, but it is safe to assume that Russian gas to China will be sold at lower margins compared to European shipments. There are several other points of concern:

· The inhospitable climate of Siberia and relative lack of connective infrastructure means that transportation costs for feedstocks and other non-local value chain items are enormous, and have likely been underestimated;

· Power of Siberia has secondary and tertiary effects of reducing demand for Russia’s smaller liquid natural gas (LNG) export projects in the region;

· Gazprom likely underestimated the market risks of dealing with a monopsonous buyer such as the PRC;

· Lack of private competition in Russia’s gas industry will guarantee that much of Siberia’s costly-to-extract reserves will remain undeveloped

Ultimately, while a significant project for Russia and China, the consequences of this agreement are not as promising as portrayed. Moscow’s warming relations with Beijing are simultaneously a marriage of convenience, and the result of a mutual and deep-seated distrust of the Western-led global order. By anchoring itself to China with Power of Siberia pipeline, Russia closes many doors, and in the long run, endangers its own energy trade – and national sovereignty.

This piece was republished from Forbes.