Don’t Expect a BRICS Monetary Revolution Overnight – de-dollarization is a process, not an event

By Michael Power, alumnus of The Fletcher School

I do not think that – as some have breathlessly claimed – the BRICS quintet are out to replace the US dollar overnight on the stage of world capital. In the atmosphere of capital flows, they are, for now, up against a far weightier ‘opponent’: the global private sector.

Groucho Marx famously said that “I refuse to join any club that would have me as a member”. Read much of the South African commentary on the Johannesburg BRICS Summit – both explicit and implicit – and one rather suspects many of these writers would have preferred South Africa, when offered membership of the BRICS Club in 2010, to have taken the same approach.

Much of the reportage prompted by the hosting of the summit centres on the opinion that South Africa should not be in a club with China, not to mention Russia. And while economic reasons are cited in passing, most of the demurral stems from not liking the politics of some of the groups’ members: Russia above all, but China as well. (Thus far, I have read only one objection to the presence of India in the club; none for Brazil.)

Some of this commentary even goes so far as to imply that South Africa is more naturally a member of the Western Bloc led by the US and, by being so, Pretoria should not cock a snook at these Western friends by going clubbing with their adversaries.

Let me be clear up front: I do not agree with every political policy of all our BRICS partners. In particular, I think South Africa should have voted for the United Nations General Assembly Resolution ES-11/1 on 2 March 2023 calling out the invasion of Ukraine by Russia.

Fellow BRICS member Brazil did; so too did fellow SADC members Botswana and Lesotho. Other African countries that voted to censure Russia were Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Ghana, Nigeria, Zambia, Benin, Cabo Verde, Chad, Djibouti, Gabon, Liberia, Malawi, Mauretania, Mauritius, Niger (not now?), Rwanda, Seychelles, Gambia, Tunisia and Kenya.

The latter’s UN ambassador, Martin Kimani, spoke eloquently in the debate, noting that just because Kenya was non-aligned, that did not prevent it from standing up for the principles to which it adhered. In particular, he characterised Russia’s behaviour as imperialist in that it stoked “the embers of dead empires”.

Just because Brazil voted against Russia’s actions does not and should not preclude it from also being a member of the BRICS Club. After all, Brazil – like most of the countries in the Western Bloc – are still co-members of a slew of clubs where Russia remains: the UN, the IMF, the World Bank and the WHO, to name but a few.

While it is understandably impossible to rid this discussion of its political overtones, the BRICS Club is first and foremost an association centred on economics: one might even claim it was “founded” by Goldman Sachs!

In particular, as an organisation, it is raising a variety of topics about the lopsided financial geometry of today’s world. (I attribute much of this misassignment above to the mistaken habit of not being able to distinguish geopolitics from its near relative, geoeconomics. But not all international dealings are political; some are far more economic in nature.)

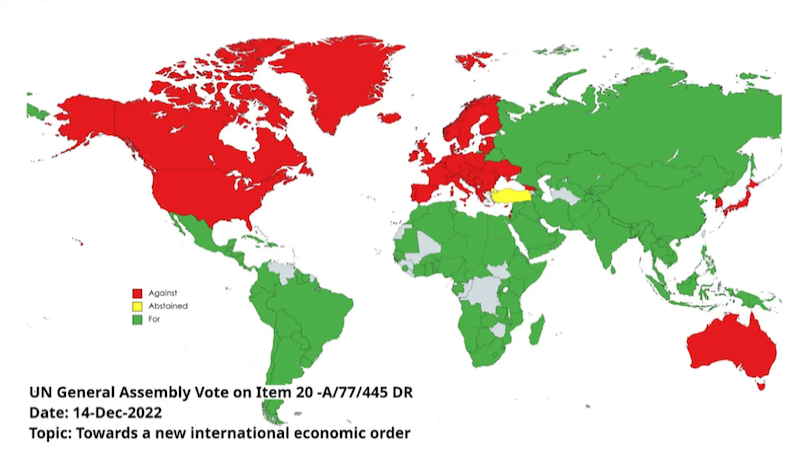

As the map below strikingly illustrates, no one event has crystallised the chasm in geoeconomic thinking opening up between the West and the Rest than a little-noted vote in the United Nations General Assembly on 14 December 2022. Under the subject title “Towards a New International Economic Order”, en bloc the Western Bloc – 50 nations – voted against it. The Rest – 123 nations, all save abstaining Türkiye – voted for it.

And the latter group embraced nations of all varieties: from Uzbekistan to Uruguay, from Singapore to Senegal, from Cambodia to Colombia and from Mauritius to Mauritania… plus, of course, the five BRICS nations. And all the African nations that voted against Russia.

The matters that concerned the overwhelming majority of the General Assembly vote were varied and on this it serves to quote the assembly’s resolution verbatim: “By its terms, the Assembly expressed concern over the increasing debt vulnerabilities of developing countries, the net negative capital flows from those countries, the fluctuation of exchange rates and the tightening of global financial conditions, and in this regard stressed the need to explore the means and instruments needed to achieve debt sustainability and the measures necessary to reduce the indebtedness of developing States.”

Capital outflows to the US from the developing world are, for many of the latter, hugely significant and burdensome in their economic lives.

At the risk of oversummarising and so oversimplifying, the West – 29% of the votes cast – did not want to change the status quo, while the Rest – 71% of the votes cast – were in favour of reconstituting the basis upon which the global economy operates. Today’s BRICS Club – while in no way carrying a mandate from or on behalf of the other 118 nations – is looking for ways to achieve some of the economic objectives set out in this UN debate.

As I noted above, much of the criticism levelled by writers in South Africa at the BRICS Club is built around the Marxist (Groucho!) charge that “this is not a club of which South Africa should be a member”.

For the balance of this piece, I will take the road less travelled – as often, the longer and harder route – and raise questions as to whether South Africa should instead unequivocally throw in its lot with the West and in particular the US. Again, this would be for reasons of economics not politics.

Kindness of foreign strangers

On 1 September 1961, President-elect John F Kennedy captured the zeitgeist of his age when he noted:

“I have been guided by the standard John Winthrop set before his shipmates on the flagship Arabella three hundred and thirty-one years ago, as they, too, faced the task of building a new government on a perilous frontier. We must always consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill – the eyes of all people are upon us.”

Back then, who could not have been captivated by JFK’s eloquence? Today, for many the US still remains the bright shining light on the hill: polls tell us many foreigners still look upon it with favour. But a forensic look at the US’s place in the world of finance reveals a darker story that lies beneath, one unseen by many.

Leaving aside the US’s increasingly fractious politics – again we are talking geoeconomics here! – beneath the glister and gloss a rather bizarre picture is emerging. The US gets by in large part by borrowing “other people’s money”, and by that, I mean the savings of foreigners.

It is this kindness of foreign strangers that enables the US to fund its external account. And that kindness is then directed internally towards helping fund the ballooning Federal deficit. Yet, as will be noted below, on a net basis, foreign strangers do not “express kindness” towards the equities of US Inc.

And, at the risk of drowning the reader in big numbers, this quantum of foreign kindness is not small: as will be detailed below, last year’s amount was more than $1-trillion. This speaks directly to a phrase from the UN General Assembly’s motion: “the net negative capital flows from those (developing) countries.” Capital outflows to the US from the developing world are, for many of the latter, hugely significant and burdensome in their economic lives.

Roots in 1944

To understand where the pattern of today’s world of financial flows comes from, one must first step back. In the aftermath of World War 2, the framework of global finance was ordered under 1944’s Bretton Woods Agreement. Exchange rates were mostly fixed, the US ran a small current account surplus and, with US Inc taking the lead, that American surplus was in turn invested – recycled – abroad.

This equilibrating arrangement continued until the late 1960s when a shrinking US trade surplus signalled trouble ahead. This turnaround resulted in large part from the budget deficits arising from the Guns AND Butter policies of Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon B Johnson: the expensive fallouts both from the US’s entry into the Vietnam War abroad and LBJ’s Great Society Program at home.

The net result was that the US no longer invested its surplus capital into the world; rather the US started expecting the rest of the world to invest their surplus capital – which often was not “surplus” in the sense of “not being needed at home” – into the US.

This pattern has continued ever since. And its scale has escalated dramatically: as noted above, last year, the US sucked in close to $1-trillion from the rest of the world. In other words, much of the world’s “still-needed-at-home” savings rather plugged the US’s twin deficits, both external and internal. (And be under no illusion about the extraordinary size of that internal deficit – 2022, $1.38-trillion – and the consequent ballooning of the Federal Debt: this has quadrupled in just 15 years from $8-trillion in 2007 to $32-trillion today. No wonder Fitch recently got antsy and stripped the US of its AAA debt rating!)

The US was – and remains – able to overspend because of the reserve currency status of the US dollar. Joan Robinson, Keynes’s most trusted accomplice, characterised this ability to fund ever-growing budget deficits as the natural outgrowth of what she saw as the US misapplication of true Keynesianism: “The bastard Keynesian doctrine, evolved in the United States, invaded the economic faculties of the world, floating on the wings of the Almighty Dollar.”

The US has been able to overspend in the bad times (as Keynes would have advocated) yet overspend in the good times too (which Keynes would not have advocated), all because of the “Almighty Dollar”. What would Keynes say of today’s good times in the US where, at near full unemployment, it is “allowed” to run a budget deficit of close to 10% of GDP?

In the late 1960s, it became apparent that the Bretton Woods Agreement was starting to work back-to-front: mostly in favour of the US and not very much for the rest of the world. The French finance minister at the time, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, famously dubbed this volte face, facilitated by Robinson’s “Almighty Dollar”, as the exercise of the US’s “exorbitant privilege”. (Given the Gallic identity of the speaker, would not the term “droit du seigneur” have been more apposite?)

Either way, the US had discovered that it owned a magic money tree: it could fund its deficits with foreigners – and its deficit at home too, as the two are interlinked – simply by picking money from that tree, either in the form of US dollar cash or of US dollar-denominated Treasury Bills.

The French, unhappy with this growing practice, took to converting the US dollars they received from their exports to the US into Fort Knox gold… at least until Richard Nixon wised up and suspended gold conversion in mid-1971.

The Bretton Woods Agreement was now visibly unravelling: by September 1973, the US fixing of gold’s price was abandoned altogether and by January 1976, the Jamaica Accords ended the Bretton Woods Agreement.

Since then, world finance has become, for all intents and purposes, a free-for-all where one winner in particular nearly takes all. In 2022, the US – with 4.3% of the global population – generated more than 60% of all current account deficits worldwide.

And, though the two are not linked one-for-one, this external deficit is in large part related to the US running a 2022 $1.38-billion budget deficit, itself more than 40% of all such deficits produced worldwide. Yes, some nations – notably those with capital controls – have elected not to take part in this US-orchestrated merry-go-round, a financial vortex where the US sucks in capital, mostly in return for dollar-denominated, never-to-be-truly-redeemed IOUs.

In Ross Perot’s 1992 opposition to the US joining the Nafta accord, the US presidential candidate famously forecast that US membership would result in “a giant sucking sound of jobs being pulled out of this country (by Mexico)”. Today, the Developing World hears a different giant sucking sound – of capital being pulled out of their world by the US.

In this light, it is worth re-reading why the Rest was so unhappy in that December 2022 UN General Assembly resolution:

“By its terms, the Assembly expressed concern over the increasing debt vulnerabilities of developing countries, the net negative capital flows from those countries, the fluctuation of exchange rates and the tightening of global financial conditions, and in this regard stressed the need to explore the means and instruments needed to achieve debt sustainability and the measures necessary to reduce the indebtedness of developing States.”

On pointing out this disequilibrium to friends, their free-market response (to which I would have normally been sympathetic) was that because US Inc uses these foreign capital inflows so efficiently, its deserves to receive them: it is but an arrangement that reflects the natural order of capital’s “best return-seeking behaviour”. (Besides, with the US’s weighting in the MSCI’s ACWI Investable Market Index at more than 60%, is it not “equilibrating” that the US’s shares of global current account deficits and so capital account surpluses are also close to 60%?)

And, for a period after the 1976 collapse of Bretton Woods and the resultant era of much greater free flow of capital globally, my friends were right: US Inc used capital efficiently.

But during the 21st century, not that US Inc stopped using capital efficiently, another volte face has quietly happened, and few have remarked upon it. On a net basis (so with some positive years: 2015, 2019 and the post-Covid rebound of 2022), foreign funds have been withdrawn from US equity markets. In the 12 months to June 2023, equities worth a net $92.2-billion have been sold by foreigners.

The proceeds of these sales may have been directed in part towards US bond markets: over the same period, foreign net purchases of Treasury and Agency Bonds totalled $1,017.1-billion. (Here I rely on the excellent TICS Data monthly summary produced by Ed Yardeni which parses US capital inflows.) And, in large part, this explains how (though there are other secondary categories of flows) 2022’s US current account deficit of $943.8-billion came to be financed.

An important distinction underlies the foreign flows into US Treasury and Agency bonds: they were overwhelmingly from private sources – $892.6-billion – with far less from public or “official” ones – $124.5-billion.

This distinction speaks to the scale of the challenge that BRICS nations might face towards the idea of “starving” the US of increases in their foreign exchange reserves recycled from their central banks: there simply is not much money from non-Western “official” sources (so outside of Europe and the UK; Japanese flows are broadly neutral) currently flowing into the US as it is. Again, that foreign support for the US bond market is coming overwhelmingly from the foreign private sector, not the foreign public sector.

Is this US addiction to debt one upon which the rest of the world – and especially the non-Western World – should remain dependent?

Summarising the above and at the risk of repetition, the US consumes 60% of net mobile capital flows globally to fund its current external overspending and help fund its current internal overspending.

And that domestic expenditure mostly supports either consumption or defence: only a small share of the current Federal budget could be categorised as investing in the US’s future – 73% of all US government spending is now mandatory or on debt interest payments and this “non-negotiable” spending consumes 94% of all Federal government income.

Within a decade, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts “non-negotiable” items will consume more than 100% of Federal income, meaning ALL discretionary items will have to be debt funded. Meanwhile, the CBO forecasts the US Budget Deficit will almost double from $1.38-trillion in 2022 to $2.5-trillion in 2033.

It is this extraordinary quantum of US government overspending that is the darker story that lies beneath global finance today, one which the non-Western world is growing weary not just of indulging but helping to fund. Is this US addiction to debt one upon which the rest of the world – and especially the non-Western World – should remain dependent?

Chipping away at dollar hegemony

This sombre observation sits with the now-revealed preference of the BRICS nations to begin reducing their dependence on a US debt-drenched global financial order and disintermediate trade flows that go via that Almighty Dollar.

For now, the BRICS nations can do little to redirect the relatively small official capital flows they can influence away from US dollar instruments. (That said, they do have the option of withdrawing from their stock of US dollar assets, for instance by switching their foreign exchange reserves and bond holdings into other currencies; this they have been doing.)

I do not think that, as some have breathlessly claimed, the BRICS quintet are out to replace the US dollar overnight on the stage of world capital. In that atmosphere of capital flows, they are for now up against a far weightier “opponent”: the global private sector.

Still, many countries – yes, led by the BRICS – have started to chip away at the hegemony of the US dollar. Economists consider there to be four functions of money: as a store of value, as a unit of account, as a standard of deferred payment and as a means of exchange. The US dollar’s position is much more secure in the first two functions than the latter two. And the first two functions dominate the reason for the pervasive use of the US dollar in the atmosphere of capital flows.

Some disintermediation is now taking place in the third function with the BRICS Bank intent on making advances in the “five Rs”: renminbi, rupee, ruble, real and rand.

The last function – that of a means of exchange – deals with the atmosphere of trade flows. And collectively the BRICS Club – likely enlarged to include heavyweights from the other 118 disaffected nations – has started to move the needle against the US dollar.

But do not expect a monetary revolution overnight: de-dollarisation is a process, not an event.

(This post is republished from Daily Maverick.)