Polina Beliakova on How the Kremlin Kicks When It’s Down

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s trust ratings are at historic lows. So are levels of popular satisfaction with Russian government authorities and economic policy. This discontent recently spilled into the streets with mass demonstrations against the Moscow’s authorities decision not to register the independent candidates for the City Duma elections. The images of riot police beating the protesting Muscovites went viral. Popular Russian celebrities with millions of followers on social media called upon their subscribers to join the protests. Dissatisfaction with the regime is not limited to the capital: In Russia’s European North, the citizens of Arkhangelsk oblast are fighting against the construction of a massive landfill. Earlier this summer, in the Ural city of Yekaterinburg, people protested the local governor’s plan for building yet another church in place of a park. The Kremlin is losing the public’s tolerance to the severe mismanagement of the state. How will this domestic turmoil affect Russia’s international behavior?

Some commentators of Russian politics suggest that Putin uses international adventures to compensate for his decreasing popularity at home. For example, former Georgian president and long-time Putin opponent Mikheil Saakashvili recently pointed out that when Putin’s public support decreases, he escalates ongoing international conflicts or launches new ones to galvanize support at home. This assumption is consistent with a diversionary war argument: To draw public attention away from problems at home, leaders start a war that boosts popular support for the government.

Interestingly, Putin’s track record suggests that the opposite is true: Russia does not go to war when domestic support is at its lowest. Does this suggest that Putin will practice restraint in foreign policy as he deals with discontent at home? That conclusion would be premature. Low public approval does not limit the Kremlin’s ability to advance its foreign policy objectives using nonviolent means. Thus, Russia observers can likely expect covert and cyber operations as well as bold diplomatic moves that will divert the public’s attention at cost lower than the use of force.

Why is that?

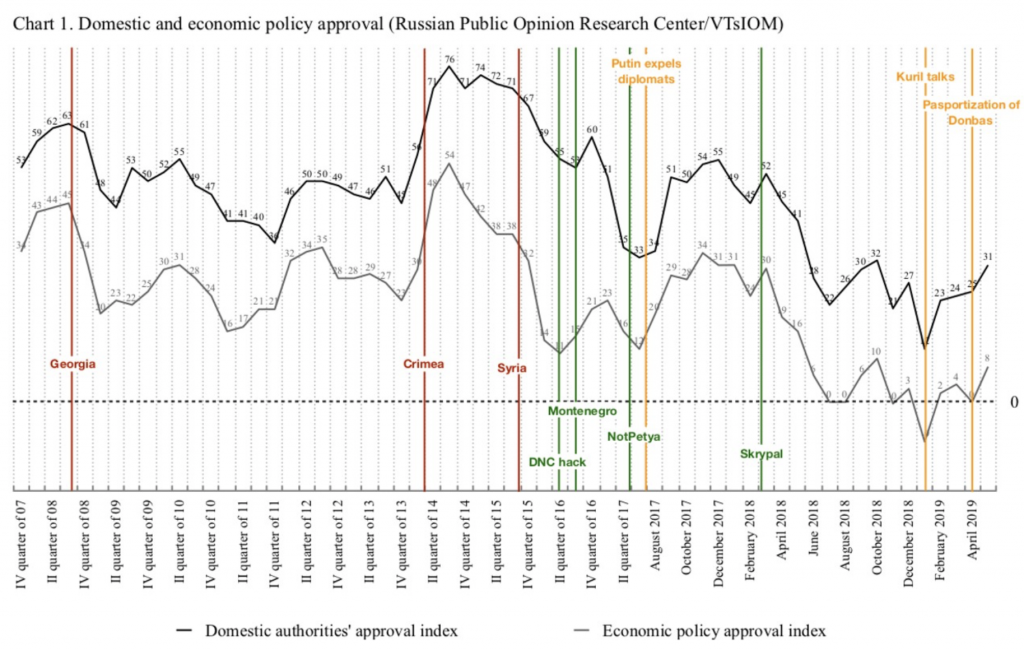

Figure 1: Domestic and economic policy approval in Russia. (Russian Public Opinion Research Center/VTsIOM)

First, relatively high levels of approval for domestic and economic policy (See Figure 1) preceded previous major episodes of Russia’s international offensives — Georgia in August 2008, the annexation of Crimea in March 2014, and the intervention in Syria in September 2015. Moreover, despite an overwhelming increase in public support after the annexation of Crimea, a decrease in domestic approval for the government’s performance followed Putin’s two other audacious moves. Thus, Russia’s aggressive foreign policy does not correlate with public support for the government in a way consistent with the diversionary war argument.

Second, given the decreased level of approval for government authorities and economic policy, expensive foreign endeavors may only exacerbate popular dissatisfaction, and there are signs that Putin does pay attention to fluctuations in the public’s mood. For instance, Putin’s four-hour call-in show on June 20 focused mostly on the questions of inadequate salaries and poor infrastructure. He also underscored that the state’s greatness has to be reflected not in arms spending but in the growing economy — the next strategic priority for Russia. Similarly, in a February 2019 speech he did not advertise Russia’s plans for the next great victories in the international arena like in previous years, but emphasized the importance of welfare, education, and economic health. By contrast, in 2018, Putin started a similar address by mentioning the conquering of new lands and space, and stressing the fatalistic importance of today’s choices for the future in which not all countries will be able to remain sovereign. This should come as no surprise. In May 2019, Levada Center polls indicated that Russians’ willingness to bear the financial burden associated with the annexation of Crimea had significantly decreased over the past five years. Given the unprecedented low levels of approval for economic policy, it is unlikely that another daring and expensive international bid will ignite enthusiasm at home and produce the outcomes expected from diversionary use of force. With a diversionary war off the table, should we expect Russia to keep a low international profile due to domestic troubles? Well, yes and no.

Yes, but only in the sense of a Russian proverb: The quieter you go, the farther you’ll get. Russia’s recent record shows that in the past, even dramatically low levels of support did not discourage the Kremlin’s use of covert action and cyber operations. The record suggests that with or without domestic approval, Russia’s international behavior largely remains consistent with the strategy of raiding — the use of limited means to achieve particular political objectives relying on infiltration, surprise attack, and swift withdrawal.

For example, in 2016 domestic approval ratings dropped to levels not seen since before the annexation of Crimea as the ruble exchange rate plummeted and Russian truck drivers (not Putin’s usual political opponents) continued their countrywide strike against the road tax. At the same time, internationally, Russia orchestrated the hacking of the Democratic National Convention and a coup plot in Montenegro. Similarly, in June 2017, domestic support for the government and its economic policies reached a new historic low. Amidst the ongoing truckers’ dissent, a separate wave of protests in 154 Russian citiesoverwhelmed the domestic political stage following the Anti-Corruption Foundation’s exposé of Dmitriy Medvedev embezzling budget money for luxury goods. As these events unfolded at home, notPetya malware attacks, which the CIA later attributed to Russian military intelligence, hit the world stage, striking multiple targets ranging from the world’s biggest container shipping company in Denmark to Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine. Of course, given the inherently secretive nature of these operations, they were not supposed to boost the domestic support for the government but served to advance Russia’s international agenda regardless of the turbulence at home. While these observations are not sufficient to argue that low public support causes Russia’s use of clandestine operations, it is fair to expect that economic concerns may encourage the Kremlin to prioritize low-cost means of foreign policy. By and large, the above examples clearly indicate that domestic troubles do not tie the Kremlin’s hands when it comes to advancing its international objectives through covert and cyber offensives.

Additionally, plummeting approval rates are not likely to contain (and even might encourage) the Kremlin’s bold symbolic political gestures, the economic costs of which are not immediately apparent to the Russian public. For instance, Putin’s order to downsize the U.S. mission in Moscow and the subsequent diplomatic crisis diverted media attention amidst the second wave of anticorruption protests in 2017. Moreover, as a response to U.S. sanctions, the president’s order projected an image of a strong state that won’t keep quiet when treated unfairly under “an absolutely contrived excuse” of Russia’s interference in U.S. domestic affairs. Likewise, in fall 2018, Putin’s offer to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to sign a Russo-Japanese peace deal, and the following discussion about the return of the Kuril islands, coincided with Putin signing an unpopular pension reform bill that raised the age of retirement higher than the average life expectancy in many Russian regions. Russo-Japanese talks took over the headlines when the unpopular pension law entered into force, and domestic approval rates sank so low that for the first time in the history of Putin’s Russia, the index of support for economic policies broke the bottom and went below zero (See Figure 1). These bold but low-cost foreign policy moves do conform to diversionary war logic but allow the Kremlin to divert public attention at a price far cheaper than the use of force.

Of course, the above observations fall short of proving robust causal links between the government’s domestic support and Russia’s foreign policy going in one direction or another. Nevertheless, they illuminate two critical points: First, it is erroneous to argue that low approval rates at home are the reason why Putin will launch another war. Second, one should not expect the weak domestic support to hold the Kremlin at bay since domestic troubles had not prevented the Kremlin’s cyber and covert actions before. As previous record shows, when the Kremlin is down, it still kicks, and sometimes with serious international consequences.

This piece was republished from War On the Rocks.