International Law, Remedial Secession, and the Self-Determination of Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh

By Alex Avaneszadeh, MALD 2023, The Fletcher School

International law has much to say in support of the right to self-determination. This is particularly in reference to internal self-determination, defined as a group’s pursuit of its political, economic, social and cultural development within the state in which they reside. But what if a particular group is persecuted and the state systematically prevents them from exercising their right to internal self-determination? In these situations, when pursuing domestic remedies becomes futile, groups can opt to exercise their self-determination externally, where the remedy is to declare independence from the parent state. In a non-colonial context, this type of external self-determination is doctrinally referred to as “remedial secession.”

Remedial secession as a form of external self-determination holds less weight as an international legal right than does internal self-determination. But the fact that it holds any legal weight at all means that the international community, particularly states, have demonstrated a degree of state practice and opinio juris, meaning acceptance as law, that gives the concept of remedial secession a soft law basis. The international recognition of Kosovo, the International Court of Justice’s 2010 Kosovo Advisory Opinion, and various national court decisions have all set the precedent of state practice and opinio juris regarding the conditions required for groups to exercise remedial secession as a right.

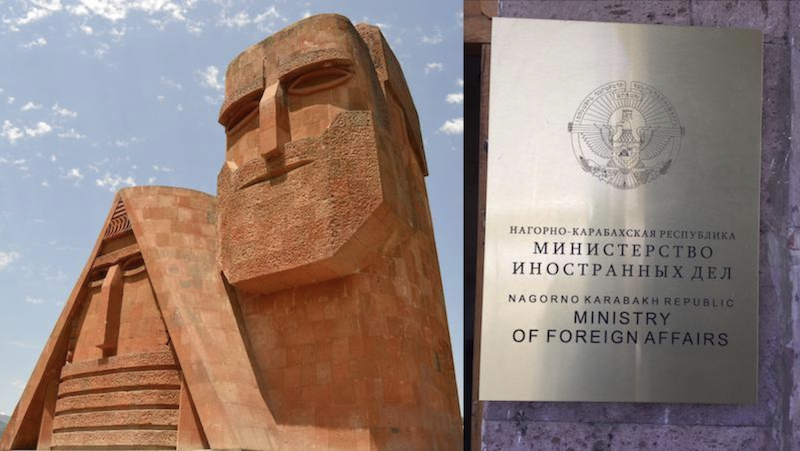

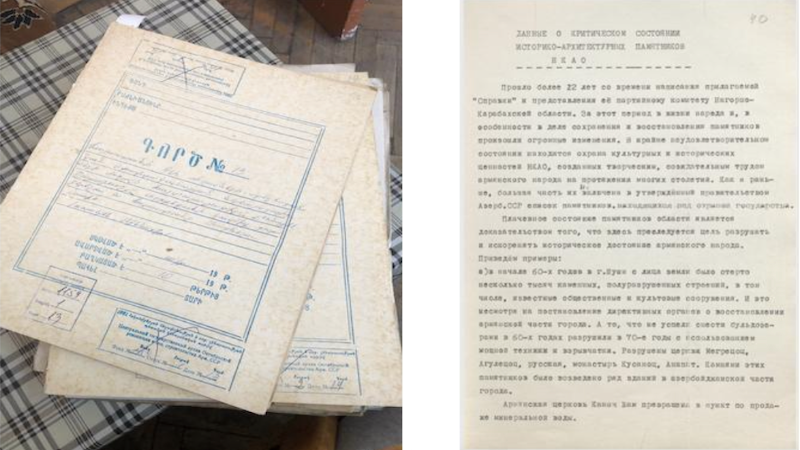

Thanks to a generous research grant from the Russia and Eurasia Program at The Fletcher School, I traveled to Armenia in the summer of 2022 to conduct research at the National Archives of Armenia for my capstone thesis on Nagorno-Karabakh’s remedial secession from Azerbaijan. This unique fact-finding opportunity in the archives allowed me to uncover evidence that revealed a policy of socio-economic and -political persecution of Armenians in the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) of Soviet Azerbaijan. Gathering this information was crucial; in order to understand the motive behind Nagorno-Karabakh’s secession, one must first understand the 70 years of subjugation and neglect experienced by NKAO Armenians under the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic.

In 1988, Armenians in the NKAO, in the spirit of glasnost and perestroika, organized political demonstrations and petitioned the Supreme Soviet in Moscow for the NKAO’s administrative transfer to Soviet Armenia. Between 1988 and 1990, those demands were met with ethnic pogroms against Armenians in various Azerbaijani cities outside of the NKAO. Subsequently, in 1991, Nagorno-Karabakh’s autonomy status was abolished by the newly independent Republic of Azerbaijan.

For the past 30 years, the Aliyev dynasty has ruled the country with an iron fist. To put this into perspective, Freedom House’s 2023 democracy index scores Azerbaijan significantly lower than Russia and Iran when it comes to political freedoms and civil liberties, placing it barely above Taliban-run Afghanistan. Additionally, public incitement of hate speech and the glorification of hate crimes against Armenians has worsened in Azerbaijan; the ongoing humanitarian blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh by the Aliyev regime is testament to the gravity of the situation. Even after Azerbaijan’s victory in the 2020 Karabakh war, territorial claims against the Republic of Armenia have become more prevalent. Thus, the fundamental question regarding Artsakh’s self-determination is: does contemporary international law expect Armenians to subject themselves to harsh authoritarian rule for the sake of upholding the traditional principle of territorial integrity? Unfortunately, the answer leans towards yes, but remedial secession as a soft legal right helps push back on this dogmatic view of territorial integrity.

“Armenia was never present in this region before. Present-day Armenia is our land. I am saying this as a historical fact. In parallel with this, let us work together on returning to Western Azerbaijan [modern-day Armenia]. Now that the Karabakh conflict has been resolved, this is the issue on our agenda. A concept of return should be developed.” – Ilham Aliyev, President of Azerbaijan, Western Azerbaijan Community Headquarters (December 4, 2022)

States, as the authors of international law, must continue to develop the principle of territorial integrity toward being conditioned upon a state’s responsibility to protect its population. From a realist perspective, states have little to no interest in developing remedial secession as a customary right under international law. However, politics often creates law. Therefore, it is on the shoulders of those groups whose existential struggle for independence continues to challenge the traditional view of territorial integrity, bringing their political struggle one step closer to an international legal right to remedial statehood.

Read Alex Avaneszadeh’s capstone thesis here: Remedial Secession as Soft Law: The Case Study of Artsakh’s Self-Determination (2023)