Polina Beliakova Reflects on Doing Fieldwork in Russia

Polina Beliakova, Ph.D. Student, The Fletcher School

Last April, I visited Moscow for the first round of fieldwork for my research about civilian control of the military. Born in the USSR, speaking normative Russian as my mother tongue, and studying Russia for the last five years, I hoped to be “Russian enough to figure things out.” Of course, I was wrong, which allowed me to collect some funny, surprising, and sometimes disturbing memories along with useful data for my research. Below I share some of the lessons I’ve learned which might help other scholars to find what they are looking for in Moscow and save some energy, time, and money.

Meeting with People

Deciding with whom to meet in Moscow, I contacted the subject matter experts from the Fletcher Russia and Eurasia Program, the Davis Center at Harvard, MIT-Russia Program, the Maxwell School at Syracuse University, and the Higher School of Economics (Moscow). Senior scholars generously devoted their time to make sure I understand what are the dos and don’ts for conducting research on the First Chechen War in Moscow. In particular, their good advice saved me from going to the archives that would not give me access to the documents I needed and prepared me for some peculiarities in navigating in Moscow both physically and culturally.

The first thing I was about to discover is that space and time in Moscow work differently than I would expect. The city is enormous, which makes the schedules of the Muscovites unpredictable. Two implications follow. First, while my advisors and mentors strongly recommended contacting the Russian experts in advance, the people I wanted to interview were not ready to commit to any particular time often until the day of the meeting. Being on the Aeroflot flight to Russia with zero meetings scheduled, I felt like an underachiever. Later I learned that this is how things work in Moscow and ended up talking to everyone I wanted by the end of my trip.

Second, due to the on-the-spot planning, people settle the meeting details over the phone. I mean, by literally talking into the phone with their voices in real-time. Therefore, having a local cellphone number was crucial. And, of course, to buy a pre prepaid SIM card I had to provide a scan of my passport at a random cellphone shop. I soon learned that, due to the way space and time work in Moscow, conducting phone interviews was a great option to talk to the experts who could not meet with me in person.

In the end, I have met with professional and insightful people who generously shared their knowledge, connections, and even books. Interviewing Russian experts also saved me from some biases and misconceptions that the Western view on civil-military relations introduced to my thinking.

Unpacking the Archives

The second component of my fieldwork was archival research in the State Archives of the Russian Federation, Russian State Archives of the Social and Political History, and the Historical Library.

Before I departed to dig Moscow’s archives, my friend and mentor from the MIT-Russia program connected me with a former archivist from Moscow. Talking to this professional, intelligent, and strict (in the Russian caring way) woman, I’ve learned how to plan my visit and speak the language of the archives. Here are some tips I found useful:

First, most of the archives allow browsing the titles of their collections online. For instance, I visited the website of the State Archives of the Russian Federation, went to Funds (Фонды), Electronic Inventories (Электронные описи) and looked at what they have. Making notes in advance saved my time and money for staying in Moscow. Another useful piece of advice was to browse the collections of Russia’s State Library (Leninka) and the Historical Library.

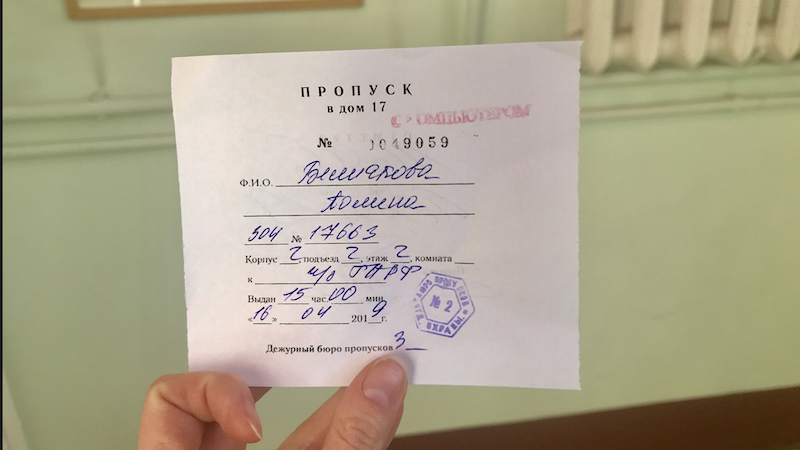

Second, the archives usually require an official letter (отношение) from the head of the department/program. It has to be on letterhead with as many stamps and signatures one can get to make it more convincing. I asked my program director to send the letter to the archives by email and brought a printed copy with me. I think only the printed version was essential for getting a permit (пропуск) to work at the archive. Having this document written in Russian (see an example) would have been fantastic, but I survived just fine with the English version.

Third, I found it useful to get familiar with the structure of the archives and learn some “archival Russian.” The employees of the archives’ reading room (читальный зал) vary on the scale of niceness from very polite and helpful to “we know that you are reporting to your organization” (this is a true story). Regardless of their willingness to help, the reading room’s employees speak and think in terms of the archives’ structure. So, to see what documents the depository has, it is most useful to ask for an inventory (опись). The inventory lists funds (фонды), sometimes referred to as collections (коллекции). Funds are titled by the topics or the names of the organizations that produced the documents and periods they cover. Each fund/collection consists of cases (дело) — physical folders with documents inside. To study the documents, one has to order the cases (дела) to be delivered from the depository to the reading room. Asking for anything outside of the archival vocabulary (e.g., a table of contents, the protocols, documents, or any other more intuitive things) would have likely yielded no result. Therefore, I made sure to translate all my requests in inventory — fund — case language: опись — фонд — дело.

One of the instrumental pieces of advice was to pay attention to the number of sheets (лист) each case of my interest includes. One can order only a limited number of sheets and cases. So, say if the limit is 1500 sheets in no more than 20 cases, one can order 5 cases with 300 sheets in each, 15 cases with 100 sheets in each, or any other combination. Wisely calculating these combinations was important, because one usually has to work through all ordered cases before receiving new. I found it useful to reserve some time for making copies of the documents (i.e., taking pictures with a phone). This service is not free, and issuing the invoice can take from two hours to five working days. Therefore, along with learning the language of the archives, doing archival math was indispensable for planning my visit to Russia.

In particular, it was crucial to study the working schedule of the reading room (annoyingly differs from day to day), the time it takes to deliver a request from the archives to the reading room (can take from one to five business days) and figure out how long does it take to issue an invoice for making the copies. While going through these calculations seemed like a headache, I did not want to take the risk of improvising on the spot. Luckily, the archives usually have the normative documents that contain these data on their websites. The same applies to the prices for different services. For instance, after doing my archival math for the State Archives of the Russian Federation, I decided that it is cheaper to pay roughly $200 so they could make the scans of 100 sheets for me than to stay in Moscow for five more business days waiting for the invoice from their financial department. Two dollars per page seemed insane before I estimated the costs of at least five-day lodging, eating, and transportation in Moscow.

Working in the archives also required some emotional discipline. In particular, I developed a super-power of minding my own business when confronted with things that seemed odd or disturbing. For example, every time going through the checkpoint at the Russian State Archive of Social and Political History, I passed by an expo about the glorious career of Joseph Stalin. As I saw the school kids listening to the tour guide’s stories about the “firm hand with which the Father of the Nation ruled our Motherland” I bit my tongue not to provoke a conversation I would immediately regret. Same happened when the archives’ employee threw a cynical look at me saying: “We know exactly what people like you are really doing in Moscow.” My mantra — be focused, get in, take what you need, get out — helped me tostay out of trouble, ignore passive aggression, and resist the temptation to make unnecessary comments (failed at least once).

Only after coming back home and starting to write my dissertation chapter, I realized how many research treasures I have brought from Moscow. It included the comments from one of the former Boris Yeltsin’s advisors about my initial hypotheses; the archival documents that shed light on the scope of the military involvement in politics, and even a well-researched study about civilian control in Russia published in 1999 in Moscow that one of the contributors to the policy process of the early 1990s kindly presented to me. This experience would not have been possible without a research grant from the Fletcher Russia and Eurasia Program and the generous support of my colleagues and mentors on both sides of the Atlantic.

Of course, above I describe only my first experience of doing research in Moscow. While I would strongly encourage emerging researchers of Russia to consult with their senior colleagues, I would also be happy to answer any questions related to the fieldwork in Russia including those not covered above (e.g., lodging, eating, transportation, etc.).