‘Price of Blood’ Soars as Russia’s Draftees Evade Service

The country’s bureaucracy and industry are struggling to supply men and weapons to the invading army in Ukraine and the situation is worsening.

By Pavel Luzin, Visiting Scholar of the Russia and Eurasia Program at The Fletcher School

Russia continues efforts to restore its badly reduced military ranks and depleted armaments. But there is a small mountain of problems despite upbeat statements from officials on manpower and manufacturing. This is causing serious problems on the frontline as human and material replacements fail to keep pace with attrition inflicted by the Ukrainian armed forces.

The spring draft campaign barely met the government targets for the recruitment of contracted soldiers for regular military units and volunteers for the “volunteer formations” of the Ministry of Defense (MoD.) For its part, the Russian military industry is proving more successful at consuming taxpayer funding than producing weapons of war.

Since fall 2022, there has been no clear official data on how many people are actually drafted into the Russian military. But despite official efforts to suppress data, some is still available. It gives an approximate understanding of what is happening and suggests the Kremlin is having serious problems.

It is losing men at a prodigious rate. At least 47,000 are estimated to have died, with a further 78,000 so seriously wounded they cannot return to the battlefield. Meanwhile, more than 11,000 items of equipment are confirmed to have been lost, including more than 2,100 tanks. The true numbers are thought to be much higher.

Replacements are, therefore, a key national priority. Take Russia’s spring draft campaign of 2023, which ran from April 1—July 15, and which was supposed to recruit 147,000 soldiers.

There are suggestions it has run into trouble. For example, just 2,500 of more than 3,000 expected recruits were sent to the troops from the Perm region during the period April 1—July 6; and sending the missing 500 recruits in the last week of the conscription campaign is barely possible. Almost the same situation occurred in Tatarstan, where just two-thirds of more than 3,000 planned recruits had been supplied by the first week of July. In its turn, the Novosibirsk region declared only 50% of 2,000 planned recruits were drafted by June 14 but promised to send the other 50% by July 15.

In another example, eight troop trains with 5,000 recruits were said to have been dispatched from the Ural regions to the Far East military district, but the first troop train carried only 300 recruits, the second about 200, the third another 200, the next train a further 200. That suggests military officials at various levels of the system may be intentionally misrepresenting the final numbers to hide their failure (this was, after all, a standard response in the Soviet Union with the often-fictional five-year plans.)

Moreover, conscripts are the main source of contract soldiers (those who extend their service) in the Russian armed forces. Consequently, the lack of draftees inevitably means a shortage of contractors. As long as the Kremlin respects its political deal with Russian society and does not send drafted soldiers to the war against Ukraine while instead “purchasing blood” through salaries for servicemen far higher than anywhere else in the labor market, the growing shortage of contracted soldiers inevitably has an inflationary effect on the “price of blood.”

As for the recruitment of contracted soldiers and volunteers, the situation is also murky. Dmitry Medvedev, the deputy head of the Russian security council, published two numbers for those signed up since January 1, 2023: 117,400 as of May 19 and 134,000 as of June 1.

About two weeks later, Vladimir Putin declared that there are 150,000 contracted soldiers and 6,000 volunteers (soldiers signing short-term three- to nine-month terms who serve in irregular volunteer formations rather than regular military units.) A few days thereafter, Minister of Defense Sergei Shoygu offered different numbers: 114,000 contracted soldiers and 52,000 volunteers, with an average daily total of 1,336 new soldiers. That would mean a total of 166,000.

These numbers are at such stark variance that there should be doubts about their accuracy, if not questions as to whether they have been intentionally falsified.

There may be an explanation, however. The Russian personnel system is now a one-way street. Since the partial mobilization started in September, all Russian contract soldiers, sergeants, and NCOs have been compelled to sign new contracts when the old ones terminate. In other words, the numbers may be artificially boosted by those already serving.

For comparison, during the five pre-war years, 2017–2021, the number of contract soldiers and NCOs in the Russian armed forces was about 400,000. The vast majority served only a two-year contract and rarely extended these for another term (the standard term for the second and following contracts is three and five years, respectively).

Therefore, the normal yearly rotation of contracted soldiers and NCOs may be conservatively estimated as 150,000. The real numbers may be even higher considering the research of the Russian National Guard, Rosgvardia, which faces similar problems to the armed forces: 60% of soldiers and 30% of sergeants retired from military service there even before the end of their first contract.

The rotation of contracted soldiers in the Russian armed forces is now almost frozen, and at the same time, there is a deficit of new recruits. This situation is confirmed by evidence from the Khanty-Mansiysk autonomous district, where the regional authorities cannot recruit enough contracted soldiers despite additional payments from the regional budget. Moreover, there is evidence that some recently recruited contracted military personnel, like tank crews, get basic training in the rear areas of the war zone. This also suggests a significant deficit of manpower.

In order to recruit new contracted soldiers for the war against Ukraine, the Ministry of Defense even decreased the term of the first contract from two years to one and completely eliminated the need to have previously served as a conscript or to have a professional education. Also, the MoD is trying to sign up foreign citizens and actively recruiting prisoners, like the Wagner Group in 2022.

The paradox is that contracted military service may even be considered a safe option for those who want to avoid war. For instance, the Russian strategic missile forces completed their annual plan for contracted soldiers in June 2023. It took on 2,000 people: 1,500 were conscripted soldiers, and another 500 chose to join the unit, which never sends its men to Ukraine. The same may be true for other branches of the Russian armed forces like the navy or air and space forces.

Will Russia’s leadership continue to accept what appears to be a significant passive resistance to service in Ukraine? How can it continue the war without further escalation and subsequent mobilization? The very real risk is that these problems (which effectively prevent troop rotation, leaving men on the frontline for months because there is no one to relieve them) may spark another mutiny. Certainly, complaints about this and other issues were enough to trigger the dismissal of one frontline commander, Major Gen Ivan Popov, in July.

Meanwhile, the authorities continue to express optimism on arms manufacturing output despite the fact that the engagement of high-ranking officials in the business administration of factories, the so-called “manual mode” of management, together with regular inter-agency meetings and reorganization efforts, shows there are serious and continuing problems in this area.

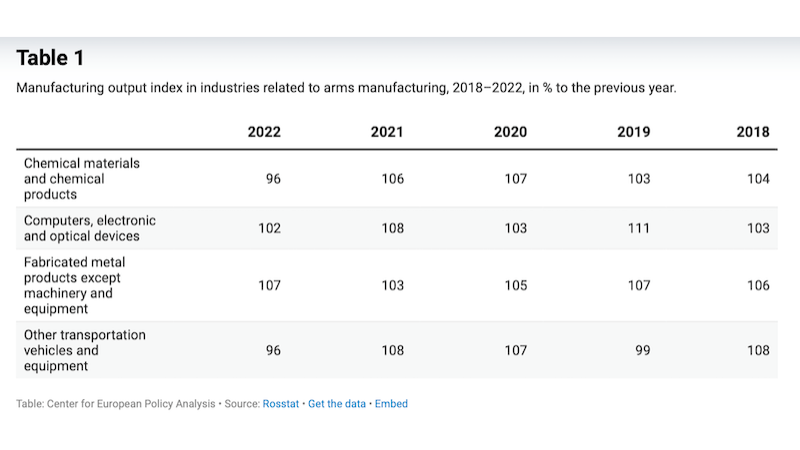

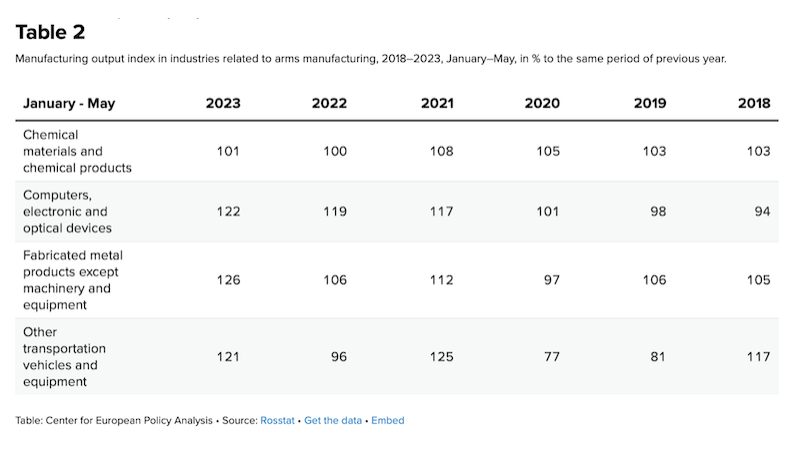

On the one hand, the manufacturing output indexes in industries related to the Russian military-industrial complex demonstrate significant increases year-on-year (see Table 2.).

Nevertheless, the methodology of Russia’s manufacturing output index relies on a formula where the physical amount of products is valued in prices of a reference period (2018.) Consequently, the real dynamics of manufacturing in industries related to the military sector may be lower than the indexes show.

On the other hand, accounts receivable from the Russian ministries were skyrocketing in 2022: from 6 trillion rubles ($81.4bn) to 9.26 trillion rubles ($135.2bn.) The cause here was budgetary payments in advance, something that will be repeated in 2023, especially in arms manufacturing. But an increase in spending does not necessarily mean a corresponding increase in output because of cost-plus inflation.

It is, therefore, difficult for Russia to replace weapons and systems lost and expended. That explains why we see more Soviet-era weaponry taken from long-term storage and sent to the battlefield. (This now includes T-55 tanks, the weapons used by the Kremlin to crush the Hungarian 1956 uprising, and the Prague Spring in 1968.)

So while Russia’s invading army will continue to fight in the occupied territories of Ukraine, its further degradation in troop and weapons quality and quantity seems inevitable.

(This post is republished from CEPA.)