Russia and the West: a dialogue of the deaf

Why does the ‘man on the Moscow omnibus’ think and speak in terms that are unpredictable and disturbing to western audiences?

By Tim Potier, Senior Fellow at the Center for International Law and Governance at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy

In 1989 and the years that immediately followed, the Russian people dreamed of the freedoms and prosperity that lifestyles in the West appeared to promise. For Russians, such dreams soon appeared to be nothing more than an illusion. Early on, state-owned assets were sold off, enriching a class of people soon to be described as ‘oligarchs’ – many of whom had been card-carrying Bolsheviks in the Soviet era. Billions of dollars were exported out of the country into Western bank accounts, paying for villas on the Mediterranean, expensive skiing holidays in the Alps, and luxury goods in the world’s most exclusive stores. As many as 90 per cent of the Russian people saw none of this. Money and competition for control led to criminality and social chaos, while the West interpreted the holding of elections and Boris Yeltsin’s electoral victories as sources of success. By 1996, the year of his second presidential election, the murder rate in Russia was nearly three times as high as in the United States.

As the 1990s proceeded, those previously in control, apparatchiks of the old bureaucracy, gradually returned to the foreground, promising a return to former certainties. Vladimir Putin was their chosen candidate, a new elite was formed and, on the surface at least, the streets and subways were safe again, and their leaders promised they would never allow Russia to return to the 1990s. The Russian people, haunted by that spectre, applauded in response.

Meanwhile, the West concentrated its Russia policy around foreign direct investments (for example, in 2003, BP invested around US$8 billion in the formation of the oil company TNK-BP) and managed to convince itself, if not the Russian people, that NGOs would solve the country’s problems and transform Russia. The country was not properly included in the general concert of Western clubs, alliances and organisations. The country’s elite and its political leaders felt humiliated. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that conversation would soon turn to the ‘Russian soul’; a belief that there is something unique in the Russian character, something impossible for a Westerner to understand. Many in the country began to follow an ideology rooted in Eurasianism, a concept dating from the beginning of the 20th century, and revived in the 21st century by figures such as Alexander Dugin, its leading exponent. Dugin argues that Russia has little attachment to European society, and that, in historical terms, if the West moved West, so Russia moved East. This Eurasian identity takes it for granted that Russia is not simply a country, but a huge territorial expanse known as Russkiy mir, a Russian world.

The West has devoted considerable attention over the past three and a half decades to countries on Russia’s periphery. That is, with those other successor states of the Soviet Union and former members of the Soviet bloc. Their membership, whether actual, pending or future in the alliance system of NATO and the European Union, and efforts, largely successful, although still very much a work in progress, to entrench liberal democracy and the rule of law, have been a remarkable achievement. Yet for many Russians, it is natural to imagine that the country is under siege and that the West is out to steal its resources. Until this view begins to change, there can be little hope that Russia will change with it.

On an instinctive level, the Russian people would much prefer to have closer ties with the countries of Western and Central Europe than with the East. It is easy to forget that 19th-century Russian writers described journeys to or from or stays in European cities to the West with ease. There were no barriers then. These were erected during the 20th century. The average Russian will also pause when the United States is mentioned. For Moscow, being seen as a peer to the US is a source of prestige; this explains why Russia’s participation in the International Space Station is seen as a matter of the greatest importance.

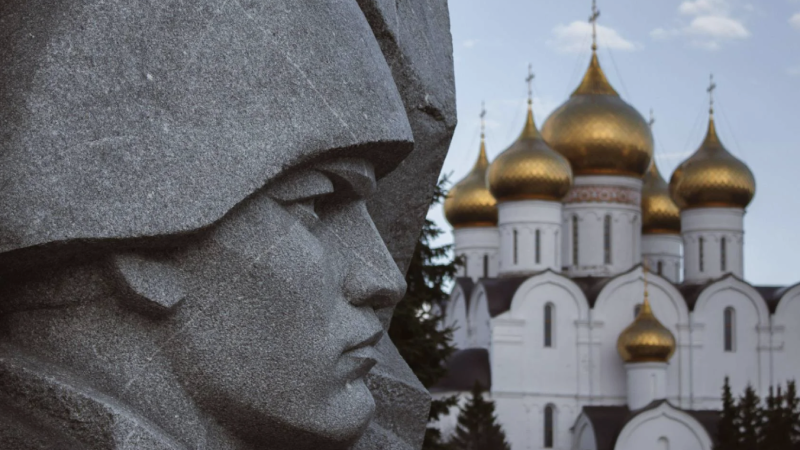

The Russian people remain intensely conservative. What tugs the heart of the average Russian (assisted by their most famous artists, being generally absent from western galleries and, therefore, largely unknown beyond) is their image of the Russian nation. That is, the countryside, the dacha, cold meats and pickles on the veranda, with an Orthodox church present not too far away (consider the paintings of Aleksei Kravchenko). For most Russians, it is the people of other European nations who have changed, not them. This is why Russian politicians make concerted efforts to align with more conservative political parties and associations in the West. The West can be saved from itself, they suggest.

The West views the leadership in Russia as wealthy from ill-gotten gains, and corrupt. And yet, the Russian people often regard Russian opponents of the leadership (overwhelmingly living outside of Russia), also, as wealthy from ill-gotten gains, and corrupt. As more attention, time and resources have been dedicated by Western officials to opponents of the Russian government, those opponents have found themselves imprisoned, in exile or worse. The Russian people continue to misread the intentions of Western politicians, just as Western politicians continue to indulge in public messaging that reinforces the public’s worst fears. Unless this dynamic can be broken, the man on the Moscow omnibus will continue to think and speak in terms that are unpredictable and disturbing to western audiences. And Russia and the West will continue to maintain a dialogue of the deaf.

(This post was republished from Engelsberg Ideas.)