Sunset For Baikonur? A Contract Dispute With Kazakhstan Flashes Warnings For Russia’s Legendary Spaceport

By Mike Eckel, Alum of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University

For nearly seven decades, Baikonur has been synonymous with the Soviet and Russian space programs.

The sprawling complex on the barren steppe of southern Kazakhstan has hurled hundreds of rockets — and ballistic missiles — into space, playing a part in some of history’s greatest spaceflight achievements: Sputnik, the world’s first satellite; Yuri Gagarin, the first human in space.

The complex survived the Soviet collapse, endured the economic chaos of post-Soviet Russia, and then helped position the Russian space agency now known as Roskosmos as a leader in continued space exploration.

The sun, however, may be finally setting on Baikonur. For Russia, anyway.

At issue is an arcane contract dispute between Roskosmos, which pays Kazakhstan around $115 million annually to lease the complex, and a Kazakh company that is partnering with Roskosmos to build a new, multibillion-dollar launch facility called Zenit-M.

Kazakh authorities have seized the assets of Roskosmos’s main operator at Baikonur, citing unpaid debts, and are demanding $26 million. Russian officials have made a $220 million counterclaim.

Without the Zenit-M complex, Russia won’t be able to launch the Soyuz-5, a next-generation rocket that Moscow hopes will replace the stalwart Proton-M. The Proton-M uses a highly toxic fuel that Kazakhstan has complained for years has polluted the landscape.

Without the Soyuz-5 rocket, Russia won’t be able to raise badly needed revenue from commercial satellite launches, a business in which Roskosmos had enjoyed some success until the invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

“It’s the latest symptom of Russia’s continual decline as far as their status as a space power,” said Bruce McClintock, a former defense attache at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow and senior researcher on space policy at the RAND Corporation, a U.S. think tank.

“I don’t think Russia is going to lose access to the Baikonur launches in the near term — maybe in the long term,” he said.

“I think the future of Baikonur looks very bleak,” said Bart Hendrickx, a Belgium-based expert and longtime observer of the Soviet and Russian space programs. “Soyuz-5 looks like the only project that can keep Baikonur alive beyond 2030,” he said. “So if these recent events would jeopardize the future of that project, then yes, that would be a big deal.”

“The situation is quite serious,” said Nurlan Aselkan, editor in chief and publisher of the Kazakh magazine Space Research And Technology. “The situation at Baikonur is turning from a stable one — if sluggish, let’s say — into a problematic one that needs to be resolved.”

Vexed At Vostochny

The seeds for Russia losing Baikonur were planted with the 1991 Soviet breakup, and the question of what to do with the world’s largest space complex, which — for Russia — was suddenly in a foreign country.

For the Russian heirs to the Soviet space legacy, keeping Baikonur’s infrastructure intact was paramount. In 1994, Moscow signed a 50-year lease with the Kazakh government that was later extended until 2050.

Russian officials also realized they needed a viable alternative. A long-standing facility at Plesetsk in the Arkhangelsk region catered mainly to military satellite launches, due to its northern latitude. Plans were hatched in the 1990s to build a new spaceport in the Amur region in the Far East: Vostochny.

With the growth in commercial-satellite launches, Russia capitalized on its reputation for reliable, low-cost rockets, garnering nearly $10 billion in revenue over the past 25 years, according to one estimate.

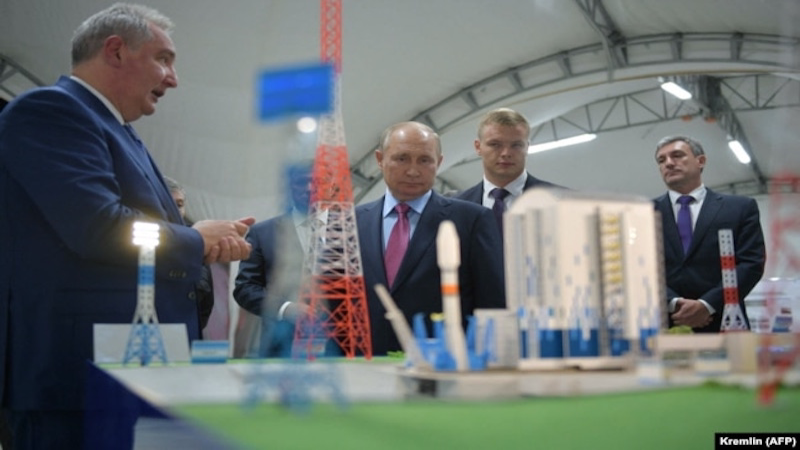

In 2015, the Russian space program, a mishmash of engineering studios, research laboratories, manufacturing facilities, and related operations, was reorganized and put under a single government entity: Roskosmos. A bombastic former deputy prime minister and ambassador to NATO, Dmitry Rogozin, was named director.

The U.S. space agency NASA had partnered with Roskosmos since the 1990s, and the two agencies worked side-by-side to build and operate the International Space Station. The Russian program got a further boost in 2011, when the United States grounded its space-shuttle fleet, forcing it to rely solely on Russian vehicles to get people and cargo back and forth to the station. NASA paid up to $100 million per ride.

Those launches all occurred at Baikonur.

Construction at Vostochny began in 2011. The project slid into a swamp of cost overruns and endemic corruption, with the costs now estimated at $7.6 billion and climbing. The first launch, a satellite, was delayed by one year until 2016; completion, set for 2018, has been pushed back repeatedly. Of the 10 successful launches conducted to date, none have been manned.

Dozens of people, meanwhile, have been investigated for embezzlement and theft. Workers have gone on strike at least once for unpaid wages.

In 2021, the top Russian auditor said that inspectors had turned up 30 billion rubles ($400 million) in financial irregularities at the agency in 2020.

A Star-Crossed Space Agency

After Russia seized Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula in 2014, Western countries, including the United States, began placing sanctions on Russian companies and top officials.

Roskosmos’s reputation was further dented by a series of mishaps and misadventures, including a still-unexplained man-made hole found on a Russian-built module at the station, an emergency landing of crew members returning to Earth, and a scandal involving the demotion of a respected cosmonaut.

(This post was republished from RFERL.)