A Modest Disagreement with Paul Krugman

Some thoughts on Krugman’s latest international relations musings.

By Daniel Drezner, Professor of International Politics at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy

I think it is safe to say that Paul Krugman’s track record as a New York Times columnistis above average. Recently, however, he has begun to weigh in on questions of international relations theory. It’s worth exploring those thoughts in greater detail.

Krugman’s primary concern is about the fraying of the liberal international order. And it’s a justified concern — there’s an awful lot of fraying going on!1 But I am not sure I agree with Krugman’s explanation for why this is happening.

First, in response to a tweet rubbishing the commercial peace, Krugman said earlier this month that, “People underestimate the role of geopolitical ideas in economic policy — the push for freer trade since World War II had a lot to do with the belief that trade promotes peace, which is increasingly hard to defend.”

Then, earlier this week, he speculated further in his New York Times column about why the Pax Americana seems to be over. He rejects the argument that it must be due to the relative decline in U.S. power; the U.S. share of global economic output has remained relatively constant since 1980. He also rejects the claim that the U.S. has been gun-shy about exercising its power by correctly referencing Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman’s recent work on weaponized interdependence.

So what is the cause? Krugman argues that the fault lies with domestic dysfunction — specifically, the Republican Party:

It seems safe to say that the world no longer trusts U.S. promises, and perhaps no longer fears U.S. threats, the way it used to. The problem, however, isn’t Biden; it’s the party that reflexively attacks him for anything that goes wrong.

Right now America is a superpower without a fully functioning government. Specifically, the House of Representatives has no speaker, so it can’t pass legislation, including bills funding the government and providing aid to U.S. allies. The House is paralyzed because Republican extremists, who have refused to acknowledge Biden’s legitimacy and promoted chaos rather than participating in governance, have turned these tactics on their own party. At this point it’s hard to see how anyone can become speaker without Democratic votes — but even less extreme Republicans refuse to reach across the aisle.

And even if Republicans do somehow manage to elect a speaker, it seems all too likely that whoever gets the job will have to promise the hard right that he will betray Ukraine.

Given this political reality, how much can any nation trust U.S. assurances of support?

Look, I should be pretty sympathetic to this argument. I argued in Foreign Affairs a few years ago that Trump has badly eroded the U.S. ability to credibly commit. I argued in Politico last week that GOP extremism was threatening to undercut U.S. national security. Krugman’s arguments should be pretty appealing to me. I clearly think there’s some validity to foreign fears of U.S. dysfunction.

But GOP malevolence and incompetence is an incomplete explanation for what is going on here. And Krugman’s skepticism of the benefits of the commercial peace hints at part of the problem.

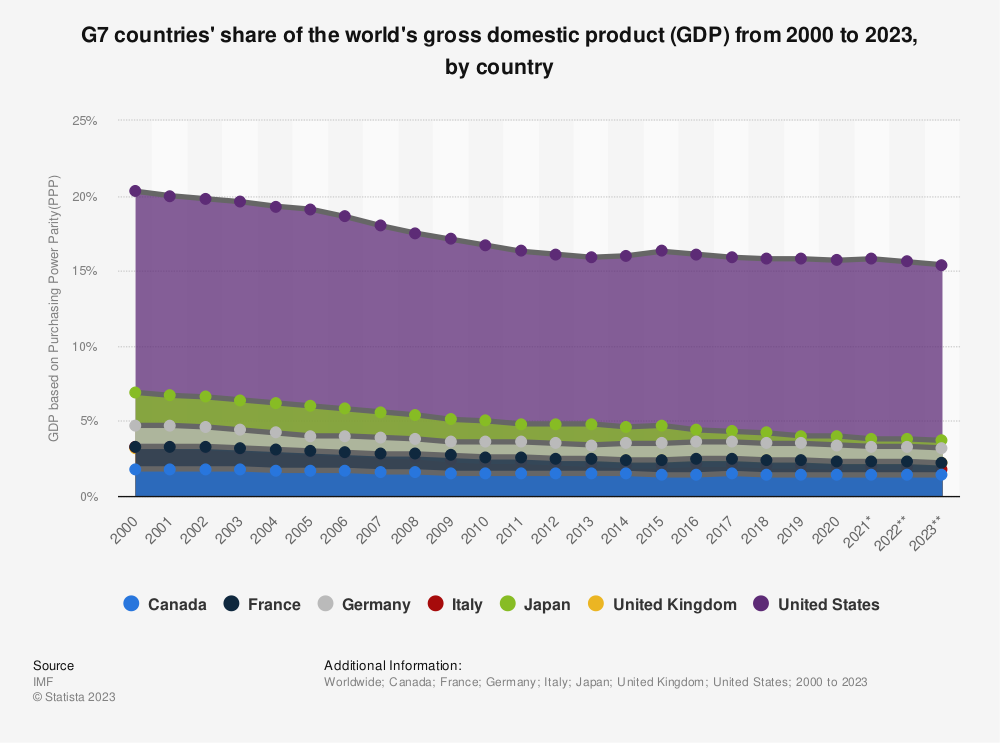

The systemic part of this story is simple. While the U.S. share of global distribution of power has stayed robust, two other key shifts are noteworthy. First, U.S. allies in Europe and the Pacific Rim do not hold nearly the same share they used to. So if one thinks of “the West” as a single grouping, it has declined. See, for example, the combined weight of the G-7 economies:2

Second, even as U.S. power has remained resilient, the rise of China means that it’s a bipolar world now in a way that was not true even a decade ago. Even if China is not going to overtake the United States, its capabilities are sufficiently large at present to function as a counterweight to American power. This gives a lot of other actors in the international system, like Iran or Russia, greater freedom of action.3

Global shifts are one part of the story. U.S. domestic politics are another part. Krugman wants to pin that domestic political shift on Republicans. It is certainly true that the GOP deserves its fair share. But I would argue — and have argued, repeatedly— that the Biden administration has earned some share of the blame by continuing the Trump administration’s more protectionist policies:

Earlier this year the New York Times’ Ana Swanson wrote, “Political parties on both the right and left have shifted away from the conventional view that the primary goal of trade policy should be speeding flows of goods and services to lift economic growth. Instead, more politicians have zeroed in on the downsides of past trade deals.” Last month the Washington Post’s David Lynch wrote, “President Biden is making it clear that the United States’ rejection of full-throttle globalization during the Trump administration was no aberration, as he continues a remarkable break with decades of trade policy that spanned both Republican and Democratic administrations.”

One reason the liberal international order is fraying is that the member countries most loosely tied to it do not see much upside to cooperating with the United States. The implicit contract of the United States maintaining an open economy has come to an end due to unilateral U.S. actions. And those actions have had bipartisan support.

I would also suggest that Republicans, the Biden team, like Krugman et al have weighted the dangers of weaponized interdependence too highly and the benefits of commercial interdependence too lightly. As I argued in my Cato Institute essay last month, the commercial peace is not an ironclad constraint but it is an important constraint on war in the international system:

Economic interdependence is hardly a cure‐all for U.S. national security concerns, but it also is not the acute national security threat that is commonly articulated inside the Beltway. Concerns have been greatly exaggerated, while the geopolitical benefits of interdependence have been underestimated. Even in 2023, China’s interdependence with the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development economies has acted as a constraint on its foreign policy behavior. Indeed, the Biden administration seems belatedly aware that it has stigmatized trade with China a bit too much. If current trends persist, however, the United States risks further geoeconomic fragmentation—and the loosening of those constraints. The worldview of malevolent interdependence is likely wrong, but those fears can be self‐fulfilling. In other words, if policymakers continue to view globalization as a threat, then the combined policy responses are likely to increase the likelihood of great power conflict….

Globalization is not responsible for Chinese bellicosity, and it is not responsible for the pandemic‐fueled shortages. While weaponized interdependence is a real phenomenon, national governments have wildly exaggerated their capacity to exploit it to advance their own foreign policy ends. The result has been a lot of sanctioning activity and very few concessions to show for it. Going forward, the danger is that in attempting to ward off weaponized interdependence, the United States, China, and other great powers will pursue policies that make it easier to conceive of great power conflict.

Krugman is right to throw some blame on Republicans for the fraying of the liberal international order. But this is not just about the GOP.

1 That said, not all this fraying is on the United States. See Andrew Exum’s latest Atlantic essayon this point.

2 Note that this measures GDP using purchasing power parity, a metric that is less favorable to the G7 than using market exchange rates. That said, I don’t think this trendline would look any different.

3 It is also possible that maybe, just maybe, the U.S. exercise of power has pushed these countries closer together.

(This post is republished from Drezner’s World.)