Maria Popova and Oxana Shevel on the Evolution of Russian-Ukraine Relations

By Rosalinde Nebiolo, MALD 2025 Candidate, The Fletcher School

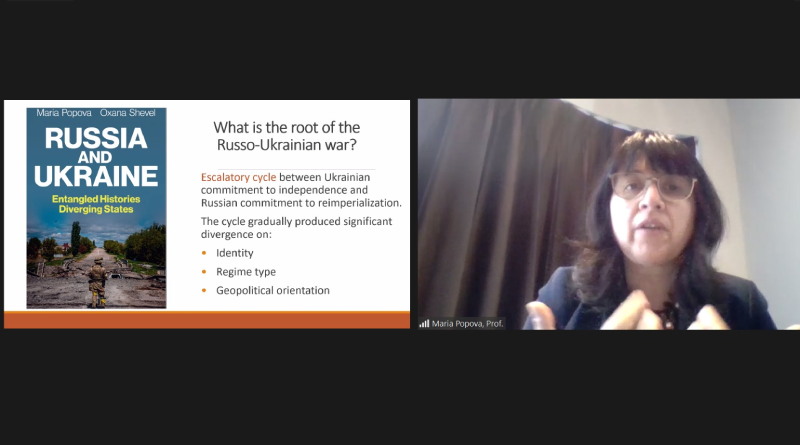

On February 13, 2024, the Fletcher Russia and Eurasia Program hosted political scientists Oxana Shevel and Maria Popova to discuss their book, “Russia and Ukraine: Entangled History, Diverging States.”

Shevel is an Associate Professor and the Director of the International Relations Program at Tufts University. Her research focuses on the post-Soviet region and topics such as nation-building, identity politics, memory politics, and democratization. Popova is an Associate Professor at McGill University and Scientific Director of the Jean Monnet Centre Montreal. She studies the rule of law and democracy in Eastern Europe, anti-corruption, and illiberalism.

The book explores Russia and Ukraine’s relationship since 1991 and how Russian ambitions have led to the war today. The authors see important cycles of the relationship between the nations centered around key events. Popova and Shevel have concluded through their research that the decision-making by Russia and Ukraine has resulted in “an escalatory cycle between Ukraine’s commitment to independence after 1991 and Russian imperialism”. Throughout the discussion, the authors discuss how these moments created a conflict that is based more on identity and cultural supremacy than previous scholars have suggested, who viewed Russian aggression as a result of security calculations.

For the authors, the 1990s started a period of profound change in public perception for Ukrainians and Russians. Shevel called the movement within Ukraine to integrate in Europe in the 1990s a project of ‘elites’ while the rest of the population had a much more complex view. Many Ukrainians were open to some form of political cooperation in the early 1990s. However, Ukraine had a general commitment and drive towards maintaining sovereignty, she said. This was contested by what Shevel described as the belief within Russian political circles that Russia was a “greater civilization or superstate.” This contestation for the authors was highlighted by the Orange Revolution.

Popova categorized the Orange Revolution as a ‘critical juncture’ for the relationship between the two states. In 2004-05, a series of political protests in Ukraine generated a cycle of democratization and reform. Viktor Yushchenko’s agenda prioritized ‘Ukrainization’ and pro-European policies. However, Popova added that the Color Revolution conversely created “an anxiety within the Putin regime that this potential for a color revolution threatens his increasing autocratization”. This anxiety about Ukraine continuing to move closer to the West would underline other policies. One example was the Minsk agreements, which created a ceasefire between Ukraine, Russia, and other armed forces in the Donbas. Ultimately, the underlying motivation linking pro-Russian policies in the early 2000s was about maintaining Russian influence over Ukraine.

Popova and Shevel found that Russian aggression is based on nonsecurity factors. What they describe as a re-imperialization movement by Putin was dictated by a need to control Ukraine. That often manifested through rewriting Ukrainian history and culture. They outlined the main alternative theories to their book, articulated most famously by John Mearsheimer. This thesis claims that Russian aggression and annexation of Crimea was NATO’s fault for expansion, which Russia saw as a security threat. Another variant is that NATO expanded into Russia’s sphere of influence. However, Popova and Shevel do not believe these theses match Russia’s actions. While Putin perceived a ‘permissive’ environment from Western states to expand, there were other factors that pushed him to pursue Crimea’s annexation and eventually war. They claim that “there is something about Ukraine which is driving Russian foreign policy, and it is not about NATO”. Shevel added that Putin’s regime promoted policies that showed “Russia wanted to repress Ukrainian memory politics [of events like Holodomor]..those issues would be there even if NATO disbanded”. They ultimately conclude rather than security, Russia’s calculus is driven by where Ukraine is moving domestically.

Today, Shevel and Popova view the end of the war in Ukraine as potentially determining Russian policies towards other post-Soviet nations. Russian re-imperialization policies may not end with Ukraine “but you start with what is possible or what is easiest to achieve”, Popova claimed, comparing it to Finland. She believes that if Russia wins in establishing control in Ukraine, “the belief that Russia is entitled to nations they used to control” will be utilized to justify aggression against other states in Central Asia and Eastern Europe.