How Russia Survived Sanctions

By Chris Miller, Assistant Professor of International History at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University

When Americans discuss Russia’s economy, words such as corruption, kleptocracy, and petrostate dominate the conversation. These buzzwords miss the point. Anyone with even a passing knowledge of Russia knows that the country is badly governed. But the interesting question is not why Russia’s economy is run inefficiently. It is how—after four years of low oil prices and economic sanctions—the Kremlin is doing so well.

Of course, concepts such as corruption and petrostate get much right. Russia’s rulers are corrupt. Former spies and secret agents dominate not only the government, but business, too. Oil and gas play as large a role as ever in Russia’s economy. But despite the corruption and despite the inefficiency, Russia has survived four years of war and sanctions mostly unscathed. It has waged war in Ukraine and Syria. It has imposed counter-sanctions on Western food producers and on Ukraine. Putin recently won re-election (flawed though the election was) with two-thirds of the vote. Russia’s elite is, broadly speaking, united around him. How did Russia manage this? Faced with Western sanctions over its nuclear program, Iran made concessions and cut a deal, which the Trump administration recently withdrew from. Even North Korea appears at least partially responsive to sanctions, and in the past has proven willing to cut a deal in exchange for sanctions relief. Russia has, at least so far, proven relatively immune to economic pressure.

How has Russia managed to survive sanctions? First, it prioritized macro-economic stability, keeping its government deficit low. Second, it pushed the cost of adjustment onto the population by devaluing the ruble. Third, it bailed out sanctioned firms via the banking system. Thus far, the system has worked. The Kremlin has retained domestic control and foreign policy independence. It has not been forced to compromise with the West.

Macroeconomic Stability

Russia has prioritized macroeconomic stability—limiting deficits, keeping government debt levels low—since Putin took power in 1999. The entire generation of people who currently rule Russia suffered through two financial crises during their formative years, first in 1991, when the Soviet Union collapsed, and again in 1998. Russia’s rulers are committed to macroeconomic stability because they personally understand the costs.

Even well-governed countries struggle to manage their economies responsibly. Oil-soaked autocracies manage less well than most. Try this thought experiment: Imagine an oil-dependent country in 1999, in which a young lieutenant colonel took power, committed to using the security services to bolster his power. Such a country exists in Russia (Putin was a Lieutenant Colonel in the KGB), but also in Venezuela (Chavez had been a Lieutenant Colonel, too.) It is worth reflecting on their differences. Putin’s economic successes are often credited to oil prices, yet commodity price swings alone cannot explain what differentiates Russia from Venezuela. Where Venezuela spent recklessly, Russia saved, paying down debt and accumulating reserves.

Chart 1 – Oil Price: Dollar versus Ruble

Devaluing the Ruble

When Russia entered the current crisis in 2014—facing falling oil prices and Western sanctions—it stuck with the Putinomics playbook. The Kremlin kept its budget deficit low, and as a share of Gross Domestic Product, it peaked at 3.4%—significantly lower, as a share of GDP, than America’s budget deficit will be in 2018. Russia balanced its budget via the second part of its crisis response, a sharp ruble devaluation that pushed the cost of adjustment onto the population. Roughly half of Russia’s government revenue is funded via taxes on oil and gas, which is priced in dollars on international markets. Nearly all of Russia’s government spending—salaries, pensions, and the like—occurs in rubles. Russia cannot control the price of oil, nor can it control how much oil it pumps. The Kremlin can, however, control the ruble price of oil. Letting the ruble fall against the dollar means that the Kremlin gets more rubles for each barrel of oil it taxes. Though the price of oil collapsed in 2014 and 2015, the Kremlin let the price of rubles collapse, too. Thus, it received roughly the same number of rubles at the end of 2015 as it had in early 2014 [see chart 1]. Its budget, as a result, was not far from being balanced.

Chart 2 – Russian Real Wages, 2014=100

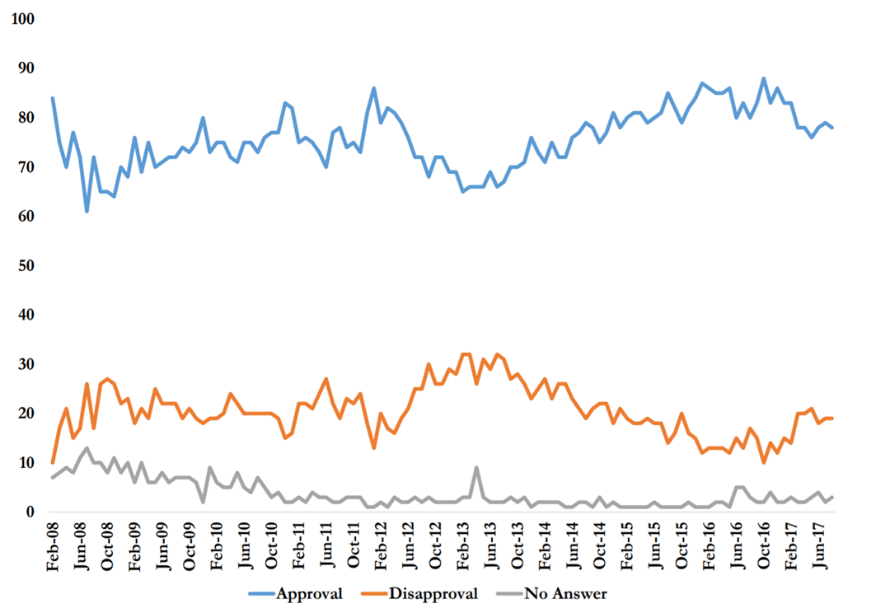

Devaluing the ruble achieved the government’s goals. The Kremlin retained the financial flexibility it needed. But it was not costless, as chart 2 shows. Ruble devaluation saved the budget by shifting the cost onto the Russian people. Imported goods, priced mostly in dollars or in euros, became far more expensive in ruble terms. As import prices increased, inflation shot upward. Yet, Russians’ incomes didn’t increase, so they became poorer. Inflation-adjusted incomes fell by over 10% at the nadir of the crisis—a level that, if it was experienced in the U.S., would bring the population onto the streets with pitchforks in hand. Yet, Russians have not mobilized in opposition to the government’s decision to make them bear the cost of the crisis—at least, they have not mobilized yet. By every metric we have, Russians approve of Putin’s activities in office. Public opinion polls say that at least 80% of Russians approve of his work. Political scientists who have researched the polling data say the true number may be closer to 70%. Either way, it is a far higher approval rating than what you might expect after a painful economic crisis, as demonstrated by chart 3, which draws on research from Yuval Weber. There have been no significant protests about wages, and hardly any strikes. Thus, the government has no incentive not to make the population pay the cost, and to keep its own budget balanced.

Chart 3 – Percent of Russians Expressing Approval and Disapproval of President Putin

Dealing with Sanctions

After the 2014 sanctions, Russia not only had to distribute the cost of adjustment—doing so on the backs of the populace—but it also had to bail out specific firms. The Kremlin chose to do this via the banking system. Rather than handing out cash directly to sanctioned firms, a policy that risked attracting attention from Russians who believed that they, too, deserved help, the Kremlin hid its bailouts in the banking system.

In the year after sanctions hit, several new, privately owned banks grew rapidly, borrowing dollars from Russia’s central bank, and using this funding to provide loans to sanctioned firms. Thus, even Russia’s most heavily leveraged firms that were under sanctions survived. Since then, most of the banks that grew rapidly in 2014 and 2015—largely by lending to sanctioned firms—have gone bankrupt. Taxpayers have picked up the tab. Yet, because this bailout—of banks, but also of the sanctioned firms that they lent to—was disguised via bank loans, few Russians understood, and fewer still complained. In the long run, the government will pay tens of billions of dollars bailing out banks, funded via higher taxes and lower spending on health, infrastructure, education, and other things which make Russians better off.

After the U.S. decision to impose new sanctions on several Russian oligarchs and firms in April 2018, many analysts have asked whether Russia has the capacity to withstand a new round of sanctions. However,, so long as Russia’s population remains docile in face of failing incomes, there is no reason to think that the Kremlin cannot repeat its 2014 playbook. It would take far more serious sanctions to drive Russia’s economy toward a crisis deeper than that of 2014. Sanctioning Russian sovereign debt issuance might have that effect, or cutting it off from the Swift international payments system. But, the more that Russia’s economic problems are directly caused by U.S. sanctions—as opposed to Putin’s mismanagement—the easier it is for the Kremlin to blame economic problems on the West. Sanctions have imposed a significant long-term cost on Russia’s economy, deterring investment and modernization. But the Kremlin has been willing to bear the cost. And the Russian people have been willing to let the Kremlin stick them with the bill. Until they start complaining, the Kremlin will have the foreign policy flexibility it needs.