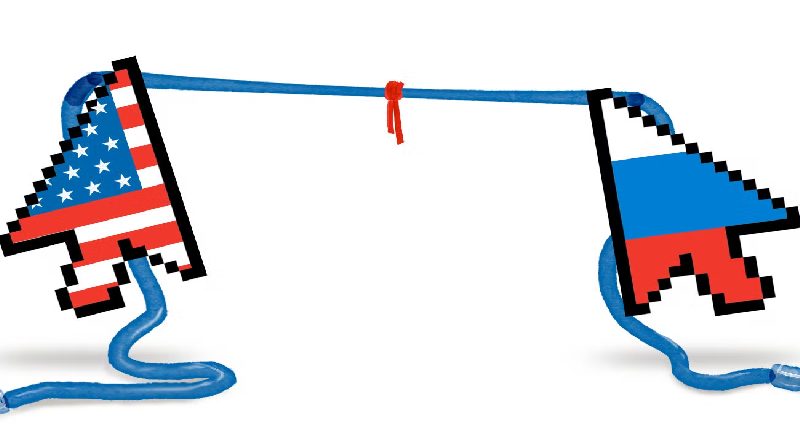

Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine Is Thwarting Its International Internet Ambitions

By Josephine Wolff, Associate Professor at The Fletcher School at Tufts University

In the grand scheme of tensions between Russia and the United States, the election that took place last week in Romania for the new secretary-general of the International Telecommunication Union was relatively tame. It was a race between two candidates—one Russian and one American—for a largely bureaucratic position running the ITU. An international organization founded in 1865, originally to coordinate telegram communications between countries, today the ITU coordinates international issues related to radio spectrum, long-distance calling, and satellite orbits.

On a practical level, it might not really matter who won the election—as it stands, the secretary-general doesn’t have the power to remake the internet. But as several commentators pointed out in the lead-up to the vote, the vote was still incredibly important, as the 193 member states of the ITU had to decide whether they align with Russia’s vision for the future of the internet or with the United States’. If a lot of countries voted for Russia’s candidate, that would have been a strong sign that they wanted to see control of the internet shift to the ITU, as Russia has long advocated. That would mean potentially putting the ITU and its member states in charge of deciding who gets to own which domain names or when to add or remove websites from the internet’s global addressing system—decisions that may effectively shape what the internet looks like.

So it was a big relief for the U.S. and its allies when the American candidate, Doreen Bogdan-Martin, beat former Russian deputy telecommunications minister Rashid Ismailov, with 139 votes to Ismailov’s 25. It was a sign not just that the United States could control the agenda of the ITU for the next four years but, much more importantly, that the large majority of voting members were supportive of U.S. leadership at the organization, and more broadly, supportive of the U.S. goal of maintaining a model of internet governance where governments are not the final decision-makers about how to distribute online resources like IP addresses and domain names; civil society, corporations, and other stakeholders have a say, too. That was a particularly big deal because many more countries—not just Russia—have been skeptical of that model of governance in the past, and wary of how much influence the U.S. wields over the internet.

But Bogdan-Martin’s decisive victory suggests that Russia’s war with Ukraine has alienated many of the other countries that it might once have been able to muster to support a more government-centric model of internet governance. Where once Russia was able to rally nearly half of the ITU countries with accusations that the U.S. is too powerful when it comes to running the internet, now the vast majority of those same countries seem to prefer U.S. leadership to a Russian alternative—and that’s a shift that could have profound implications for the future of the internet and who gets to run it. It’s a striking example of how Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is thwarting its international ambitions related to the internet, an outcome that may well frustrate China, Russia’s long-time ally in rallying ITU members to oppose US leadership.

The ITU deals with international telecommunications issues like long-distance calling rates, radio spectrum use, and satellite orbits. It also develops some technical standards and helps promote broadband access. What it doesn’t do—and has never done—is actually administer any of the internet’s infrastructure or resources (like IP addresses and domain names). Partly, that’s because a lot of internet infrastructure is owned and operated by private companies, and partly that’s because by the time many of the ITU member states became interested in internet governance, the U.S. government had already signed a contract with a nonprofit organization called the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers to manage critical internet resources.

Unsurprisingly, many countries—especially those like Russia and China that were suspicious of the United States’ particularly close relationship with ICANN, a nonprofit headquartered in California—were not thrilled with that arrangement. Up until 2016, for instance, the U.S. government held the power to veto some of ICANN’s decisions about the internet under the contracts it issued to the organization. Even when the U.S. gave up that power—and stopped issuing contracts to ICANN altogether—many governments continued to believe that ICANN did not listen to them when making decisions. Russia, in particular, has long pushed for the ITU, where every member state gets one vote, to be the forum for internet governance instead of ICANN, where governments get no votes at all and instead offer input to the CEO and board through a “Government Advisory Committee.”

So even though the ITU is essentially a nonentity when it comes to internet governance, countries like the United States, which want to maintain the status quo of multistakeholder internet governance and prevent the ITU from seizing any additional power. They’re worried that under Russian leadership, it might make a bid for some of ICANN’s authority. There’s good reason to be concerned about that possibility, since it actually happened not so long ago.

The last time the United States squared off against Russia for a big vote at the ITU happened at the 2012 World Conference on International Telecommunications in Dubai, when all 193 members came together to negotiate the international treaty that governs telecommunications, the International Telecommunication Regulations. That vote hinged, in part, on the question of whether the ITU would assume some greater responsibility for global internet governance.

The United States and its allies pushed for the ICANN-run model of internet governance in which governments had no greater say than anyone else involved (except for, arguably, the U.S. government, since it was still four years away from giving up its administration of ICANN’s contract at the time—and had not yet announced its intention to do so).

On the other side was a group of countries led by Russia and China, pushing for the ITU to assume more control over the internet so that all countries would have a vote and governments, not private actors, would be the ultimate authorities when it came to deciding how the internet was run. That might have meant government delegates, instead of the ICANN board, deciding whether a company like Amazon could own the .amazon top-level domain over the objections of the Brazilian and Peruvian governments, or whether to delist .ru domains from the internet’s addressing system at the request of the Ukrainian government earlier this year. It wouldn’t necessarily have been disastrous for those decisions to be made by government delegations instead of ICANN, but there was also considerable fear that governments, due to their lack of understanding of how the internet works, might try to do other, more impractical things through the ITU—like dictate how their internet traffic was routed in ways that would be impossible for internet service providers to implement.

Of course, with 193 countries involved, this wasn’t just a battle between the United States and Russia—but there’s no question they were the two central figures in that fight. One op-ed in the New York Post at the time claimed that “if delegates have their way at next week’s World Conference on International Telecommunications in Dubai, the man in charge of the Web will be a Soviet-trained apparatchik from Cold War days.”

The 2012 treaty negotiations were a mess. Even though the new treaty didn’t actually wrest any authority from ICANN, 55 countries, including the United States and most of Europe, refused to sign it for fear it might move the ITU closer to assuming some control over the internet. But another 89 states did sign it, including Russia, China, Brazil, South Africa, and much of the Middle East and Africa.

So while the United States and its allies were able to keep the internet out of the ITU’s hands, they also realized that dozens of countries were fed up with how the internet was being run. Not long after, the Commerce Department announced that it was taking steps to stop administering ICANN’s contract in order to make the organization more fully independent of the US government and in 2016 the last contract officially ended. Some U.S. politicians, notably Ted Cruz, decried that change as “greatly endanger[ing] Internet freedom” because it would make it slightly harder for the US government to intervene if ICANN made decisions it disagreed with. But that, of course, was exactly the point—the change was supposed to appease the international community and reassure them that the internet was not under U.S. control.

Bogdan-Martin’s victory last week can be seen, in part, as evidence of the success of that maneuver. If dozens of ITU members were still suspicious of how much power the US wields over the global internet, presumably they would not have supported her candidacy.

But the dramatic drop in support for Russia’s agenda of having the ITU take control of internet resources can’t be attributed just to the 2016 change in ICANN governance. Many governments still find ICANN a frustrating forum for their delegations and unresponsive to their interests. In 2012, 89 members sided with Russia in ratifying the new treaty and holding open the possibility that the ITU might eventually help administer the internet. The only plausible reason for that number to have dropped to 25 by 2022 is Russia’s war with Ukraine and how wary it has made ITU members of aligning themselves with Russia or its representatives. It’s not a particularly surprising outcome given the current political climate, but it’s a striking one all the same because it suggests that Russia’s decisions with regard to Ukraine may fundamentally reshape the sides in the fight over internet governance. Now, it seems, it’s going to be much more difficult for Russia to work with China and other allies to limit U.S. influence over internet governance bodies.

Ten years ago, many ITU members viewed the United States as the aggressor when it came to internet governance—it was seen as a country that had parlayed its early investment in and development of the internet to controlling the global resources underpinning it that were now shared by the entire world. Some states worried at the time that the US government might shut off or otherwise manipulate their internet access thanks to their influence over ICANN. Last week, those concerns seemed to be much less prominent for ITU members than concerns about Russia’s aggression and instability. And if Russia can’t effectively rally other governments against the existing model of internet governance, it may be that we can go at least another 10 years before it is seriously challenged again.

This piece is republished from Slate.