The Impact of Russia’s “Foreign Agents” Legislation on Civil Society

By Maxim Krupskiy, Visiting Scholar of the Russia and Eurasia Program at The Fletcher School

ABSTRACT

This article analyzes the evolution of Russian legislation on “foreign agents” and its practical implementation over the past decade, including its impact on Russian civil society. It provides an overview of the legislation’s main aspects, an explanation of its quasi-legal nature, and an analysis of law enforcement practices. It also examines the institution of “foreign agents” and its impact on the free agency of Russian citizens with a focus on the peculiarities of the Russian social environment in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“FOREIGN AGENTS” AND “NATIONAL TRAITORS”

In his address to the parliament of the Russian Federation on the one- year anniversary of the war against Ukraine on February 21, 2023, Russian President Vladimir Putin labeled those Russians who share Western liberal ideas as “national traitors.” Specifically, he articulated that “the West will obviously try to undermine and split our society, betting on national trai- tors, who at all times have the same poison of contempt for their own fatherland and the desire to make money by selling this poison to those who are willing to pay for it.”1 Putin has a history of referring to those who

embrace Western liberal ideas in inflammatory terms, previously labeling them as “scums and traitors” whom he blamed for seeking to “destroy Russia,” thereby justifying the “natural and necessary self-cleansing of Russian society” from them.2

The roots of the contemporary Russian narrative identifying “national traitors” as an existential threat dates back to long before the war in Ukraine. In fact, it can be traced to the Russian government’s response to the “color revolutions” of the mid-2000s in post-Soviet Georgia and Ukraine. At the time, Russian officials were convinced that the “foreign or foreign-funded NGOs acting to undermine the country’s sovereignty” supported the opposition in those countries.3 Importantly, they under- stood foreign NGOs to be any NGOs either registered in, or founded on, the territory of a foreign state. In order to prevent the same from occurring in Russia, the Russian government tightened legislation against Russian NGOs funded from abroad.4

Despite the generally atomized and apolitical attitude of the Russian people, the 1990s and 2000s were a window of great opportunity for Russian civil society. Thanks to the rapid opening of borders, and, with it, greater access to international organizations and foreign funding, many civic initiatives emerged in Russia at both local and national levels. NGOs and social movements aimed at promoting and protecting human rights flourished and charitable organizations saw significant institutional growth.

This period of opportunity promoted the development of Russian civil society, thereby contributing to the normalization and legitimization of NGOs in the eyes of the population. In 2011, researchers noted that despite fragmentation of the public sphere, there was a growth of civic activity in large cities.5 At the time, they noted that “new forms of self- organization are emerging in various spheres: landscaping, leisure associa- tions, various aid societies, forms of territorial self-government, the fight against conditional housing, parents’ councils, environmental groups, [and] the growing number of independent trade unions.”6 Additionally, the researchers found that the state not only tolerated their activities but that it was even willing to collaborate on certain projects to solve social problems.7

However, amidst the street protests that took place from 2011 to 2012, the state launched a full-scale campaign against civil society in Russia. Those protests were sparked by mass falsifications during Russian State Duma elections in 2011 and the presidential election in 2012, when Vladimir Putin became president of Russia for the third time. The largest protests at that time took place in Bolotnaya Square in Moscow and were brutally suppressed.8 On July 20, 2012, the first version of the Russian

law on “foreign agents,” officially titled “On Amending Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation Regarding Regulating Activities of Noncommercial Organizations Performing Functions of a Foreign Agent,” was enacted (hereafter referred to as “Federal Law No. 121-FZ”).9 This moment represented a marked expansion of overtly repressive measures against members of Russian civil society.

The authors of the bill, namely the deputies of the State Duma, justi- fied the law on the grounds that legislation on “foreign agents” exists in many countries of the world. In particular, they referred to the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), in force in the United States since 1938, which requires any individual who acts on behalf of a foreign party (state, company, individual, etc.) to register as a foreign agent.10 However, critics pointed to uniquely repressive elements in the Russian bill, including overly vague references to “political activity” and “foreign financing,” warning that “foreign agent” could become synonymous with “spy” and “traitor.”11 This label could therefore severely undermine the credibility and reputation of NGOs, which would negatively affect their activities.

In the aftermath of the bill, 62 percent of Russians responded that they held a generally negative perception of the phrase “foreign agent,” with 39 percent believing that it referred to a “spy” and 22 percent believing that it referred to a “fifth column,” a term used to refer to a group within a country that is sympathetic to, or working with, enemies of the state.12 As this polling data makes clear, the Russian public has a difficult time disen- tangling the linkage between “foreign agents,” “spy,” and “fifth column.” Their confusion plays directly into the state’s hands because it allows the state to blur the line between criminal conduct and legal activities in order to justify greater oppression.

Inclusion of NGOs in the register of “foreign agents” in Federal Law No. 121-FZ prohibited NGOs from building further cooperation with government agencies because they were accused of acting to the detriment of Russia’s interests. At the same time, the law stated that any NGO partici- pating in a public event while receiving foreign funding could be included in the registry.13 For similar reasons, organizations engaged in academic activities faced difficulties in carrying out their activities. The government supplemented these restrictions with smear campaigns on state television channels, which were highly detrimental to NGOs’ reputations, especially since television is the main source of information for the vast majority of the Russian population.14

Over the last eleven years, Russian legislation on “foreign agents” has become considerably stricter. The first iteration of the law referred only to

NGOs that received “foreign funding” and engaged in “political activities.” Under a new federal law passed in 2019, some commercial organizations and individuals funded from abroad were labeled by Russian authorities as «foreign mass media performing the functions of a foreign agent» because they supposedly distributed foreign agent “materials.”15 A year later, a new federal law created a separate register of “foreign agents” for individuals who did not fall under the definition of “foreign mass media,” but who participated in “political activities.”16 The simultaneous existence of three separate registries made the legislation on “foreign agents” even more confusing and unpredictable.

Throughout these developments, the main characteristic of Russian legislation on “foreign agents” has remained unchanged in that the content of the legislation does not correspond with the accepted legal meanings of the words “foreign” or “agent.” The Russian legislation on “foreign agents” indicates that one can become a “foreign agent” without ever performing any agent activities, that is, without acting in the interests of a foreign state, company, or individual. In finding someone guilty of being a “foreign agent,” state authorities are not required to prove the existence of a causal link between receiving foreign funding and subsequent “foreign agent” activities.

At the start of the war in Ukraine in February 2022, Russian authori- ties actively used the legislation on “foreign agents” as a tool for suppressing anti-war protests in Russian public spaces. During the war’s initial phase, many prominent public figures who expressed anti-war positions were included in the register of “foreign agents.”17 For example, well-known Russian musicians, actors, journalists, bloggers, and lawyers were added to the registry of foreign agents, and renowned human rights organiza- tions, notably International Memorial and the Memorial Human Rights Center, were shut down by Russian courts.18 Subsequently, in June 2022, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Russia had violated the right to freedom of assembly and association (Article 11 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms) with regard to NGOs.19

In December 2022, a new law on “foreign agents” went into effect.20 In contrast to previous versions of the “foreign agents” legislation, this iteration definitively broke with the principle of legal certainty. This prin- ciple requires that any law be accessible and foreseeable.21 The new law gave authorities the opportunity to label any citizen, media outlet, or orga- nization (whether commercial or non-commercial, foreign, or Russian) as a “foreign agent,” solely on the grounds that they are under “foreign

influence,” which the law defined in vague terms. According to the law, “foreign influence” means “provision of support and/or influence on the person by a foreign source, including through coercion, persuasion and/or other means.”22 In addition, “support” means “provision of money and/or other property, as well as provision of organizational and methodological, scientific and technical assistance, and assistance in other forms by a foreign source to the person.”23

Under this law, if a person is found to be a “foreign agent,” they are prohibited from carrying out numerous activities, such as engaging in educational activities in state universities, schools, and other public insti- tutions, organizing public events, and producing and distributing mate- rials to minors. It also provides the state with sweeping authority to cancel organizations’ programs and activities even if they do not violate the law. Moreover, those labeled “foreign agent” are at risk of administrative liability and may be punished in the form of monetary fines of up to half a million rubles (approximately USD 7,000) and a jail sentence of up to five years.

The new law on “foreign agents” has given formal legitimacy to the current narrative of the fight against “national traitors,” or those who publicly declare their anti-war views, take a critical position on Putin’s poli- cies, and refuse to demonstrate their unwavering loyalty to his regime. The authors of the new law have publicly justified its more repressive bend in light of the war against Ukraine and the necessity of taking precautionary measures during wartime.24

THE INSTITUTION OF “FOREIGN AGENTS” AS A REPRESSIVE POLICY MECHANISM

A decade of evolution of the “foreign agents” legislation and its law enforcement practice has significantly impacted the strategies of Russian NGOs, independent media, and civic activists. It has also created new challenges for civil society. Given the extent of this legislation’s impact on Russian civil society, a comprehensive socio-legal analysis of this legislation is warranted.

The nature of the Russian institution of “foreign agents” is quasi-legal. In other words, despite its legal shell, it essentially functions as a repres- sive mechanism that contradicts the rule of law and, instead of upholding the interests of a democratic society, aims to erode democratic safeguards. Despite the fact that this legislation is quasi-legal, it is necessary to do a legal analysis in order to analyze it comprehensively and consider the ways in which it has been formally enshrined into legal norms.

As discussed above, “foreign agents” legislation has had and continues to have a negative impact on Russian civil society. However, this impact goes far beyond the formal legal prosecution of specific NGOs and other independent civic actors.

On the one hand, the implementation of such laws with vague defi- nitions creates conditions for the executive and judicial authorities to abuse their powers. It also erodes the high legal standard of proof that requires the executive branch to present necessary and sufficient evidence to justify its decisions. In addition, the implementation of such legislation over the years has formed a vicious judicial practice in which it is easier for courts to agree with executive authorities’ decision that a person is indeed a “foreign agent” than find this decision unlawful. In this way, the law enables judges to ensure that the person labeled as a “foreign agent” will be unable to prove their innocence in a higher court. Even among professional lawyers— representatives of the Russian Ministry of Justice and judges— this practice leads to legal nihilism, or an attitude that denies the social value of law and finds it to be the least perfect instrument for regulating social relations.

Over his decade-long human rights practice of representing “foreign agents” in Russian courts, the author has found that in the absence of clear criteria in the law for recognizing an organization or individual as a “foreign agent,” the right to judicial protection essentially becomes a fiction. Vague language renders it impossible to formulate a position on the side of the defense. As a result, the fate of a person accused of being a “foreign agent” depends solely on the arbitrary discretion of a biased judicial body whose work is designed to legitimize the position of executive authorities.

The quasi-legal nature of the law on “foreign agents” is not accidental. Some deputies of the State Duma have themselves admitted that the latest iteration of the law is intentionally worded as vaguely as possible. Oleg Matveichev, one of the authors, stated in an interview that:

the law is written in such a way that it cannot be circumvented. For the law to be effective, it is made in such a way that we can always declare a ‘foreign agent’ whoever we deem necessary…I believe that in principle there should not be any people in Russia who have any commercial, non-commercial, or other relations with any foreign people, unless they are diplomats.25

The implementation of “foreign agents” legislation not only under- mines the rule of law but also has a negative impact on society itself. Citizens who have for years witnessed how NGOs, independent media, and civic activists disfavored by Putin’s regime have been arbitrarily listed as “foreign agents” are losing faith in the law’s fairness. This experience

also inevitably leads to legal nihilism among ordinary citizens. In addition, the stigmatization of independent civic activism through the implementa- tion of this legislation makes public participation in civil society practices unpopular and dangerous. This tendency negatively affects the sustainable development of society and inhibits the growth of a tradition of participa- tory democracy.

In addition to analyzing this legislation through a legal lens, a law and development lens provides useful insights, especially given the complex influence of this legislation on Russia’s legal and social development.

Yong-Shik Lee rightly pointed out that law is relevant to develop- ment and that “although law alone cannot create successful development, it can facilitate or inhibit development by influencing actors in the economy and society.”26 Lee emphasizes that law is “a vehicle to implement a policy” and that its significance lies within its practical implementation through regulatory design, regulatory compliance, and quality of implementation.27 This understanding is highly relevant to the analysis of “foreign agents” legislation insofar as this legislation promotes legal nihilism and under- mines Russians’ positive attitudes toward civic activism and participatory democracy.

As mentioned above, Russian legislation on “foreign agents” does not meet the criterion of legal certainty, as it contains extremely vague language and enables state officials to arbitrarily include people and entities onto the “foreign agents” register. Thus, the “foreign agents” legislation allows for the violation of the constitutional principle of equality of all before the law. In Lee’s terms, such legislation is a destructive “vehicle to implement a policy” and, as such, will inevitably retard social development.

Amartya Sen’s approach to development as freedom sheds more light on the negative impact of “foreign agents” legislation on the development of Russian society. He argued that “development requires the removal of major sources of unfreedom: poverty as well as tyranny, poor economic opportunities as well as systematic social deprivation, neglect of public facilities as well as intolerance or overactivity of repressive states.”28 The legislation on “foreign agents,” originally conceived by Russian authorities as a repressive policy mechanism, is a source of unfreedom insofar as it creates unreasonable obstacles to Russians’ civic right to self-organization. Sen particularly cautioned against the dangers of the use of such mecha- nisms by official authorities, stating that “the violation of freedom results directly from a denial of political and civil liberties by authoritarian regimes and from imposed restrictions on the freedom to participate in the social, political and economic life of the community.”29

In this paper, civic agency refers to the ability of people to act as inde- pendent actors, to formulate their own social and political agenda, and to influence and control state authorities. Agency, therefore, is closely related to civic freedom and development insofar as “greater freedom enhances the ability of people to help themselves and also to influence the world, and these matters are central to the process of development.”30

Legislation on “foreign agents” fosters a negative attitude toward civic self-organization because it cultivates a sense of fear around possible administrative and criminal liability as well as resulting stigma. In addition, it destroys existing horizontal networks between civic groups. The consis- tent application of such a repressive policy mechanism undermines the free and sustainable agency of people, which—according to Amartya Sen—is “a major engine of development.”31 Thus, so long as “foreign agents” laws remain in force, development is almost impossible in Russia.

THE CIVIC APATHY OF RUSSIAN SOCIETY AND THE STIGMATIZATION OF “FOREIGN AGENTS”

There are few independent research centers in Russia today that study civil society, but two, namely the Levada Center and the National Research University Higher School of Economics, continue to collect relevant and reliable data. Both have conducted numerous studies on the degree of self- organization within Russian society, people’s attitudes toward the state and public initiatives, as well as the impact of “foreign agents” legislation on civil society. The charts presented in this section were made using data from independent opinion polls conducted by these two organizations. Results of previous studies of “foreign agents” legislation conducted by other researchers demonstrate that “foreign agents” laws create signifi- cant barriers that prevent NGOs and public associations from effectively carrying out their work because they are unable to attract funding and engage with activists and public authorities in beneficial ways.32 Moreover, the “foreign agent” label is associated with a high risk of liquidation.33 It is clear that the laws’ implementation has led to a significant suppression of the development of independent Russian NGOs, whose situation has only been further exacerbated by the war against Ukraine.

Societies with a high degree of democratic development and a time- honored culture of civic self-organization may demonstrate greater resis- tance to the impact of such restrictive laws than societies in which those elements are not present. Russia is an example of the latter. The following Levada Center and the National Research University Higher School of

Economics independent public opinion polls consistently demonstrate a low degree of public and political activity among Russian citizens.

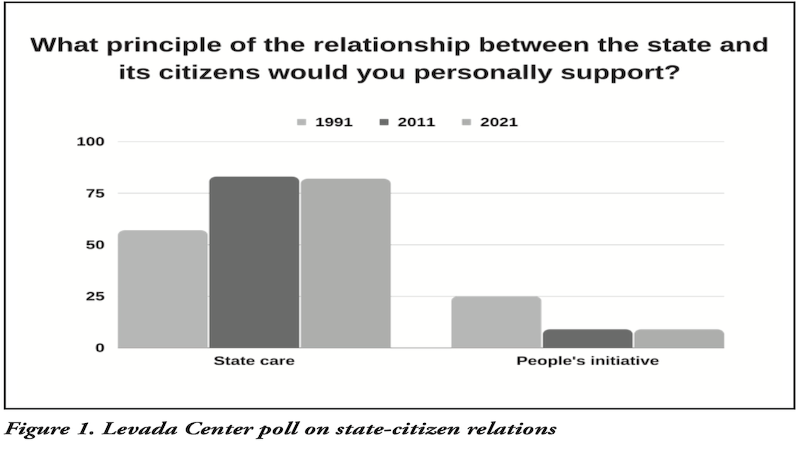

Since the majority of the Russian population, especially the elderly, expresses loyalty to the state, they distance themselves from public and political participation. Instead, they naively believe that the state will provide for them out of goodwill and that, therefore, public participation is not necessary to ensure accountability. Therefore, it is unsurprising that when asked by the Levada Center about the principles that should govern society, more than 60 percent of respondents chose the following option: “the government should take care of people.” Around 30 percent of respon- dents chose the following option: “people should be able to get what they need from the government.”34

The polling data shows that the level of support for state paternalism, or the constraint of individual freedom in favor of what authorities define as the public good, increased almost 1.5 times during the period from 1990 to 2011.35 In 2021, the percentages remained virtually unchanged, as seen above in Figure 1.36 The results of these surveys show that Russian society is rather weak in its desire for independent civic activity and in its demand for the state to fulfill its obligations to its citizens. Unfortunately, these tendencies are growing amidst rising authoritarianism and Putin’s

strengthening of vertical power. As a result, Russians perceive the state in the tradition of Hobbes’ Leviathan: as a powerful force that is not subject to control by citizens.37

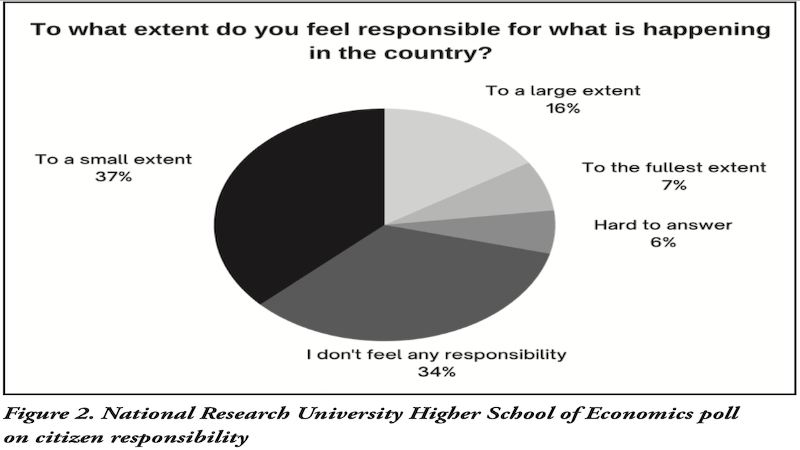

A distinctive feature of Russian society over the past twenty years is the lack of a sense of responsibility for what is happening in the country among the majority of citizens. According to surveys conducted from 2006 to 2021, on average more than two-thirds of the Russian population felt either little or no responsibility for what was happening in the country.38 Similar results are found in a survey conducted in 2011 by the National Research University Higher School of Economics (Figure 2).39

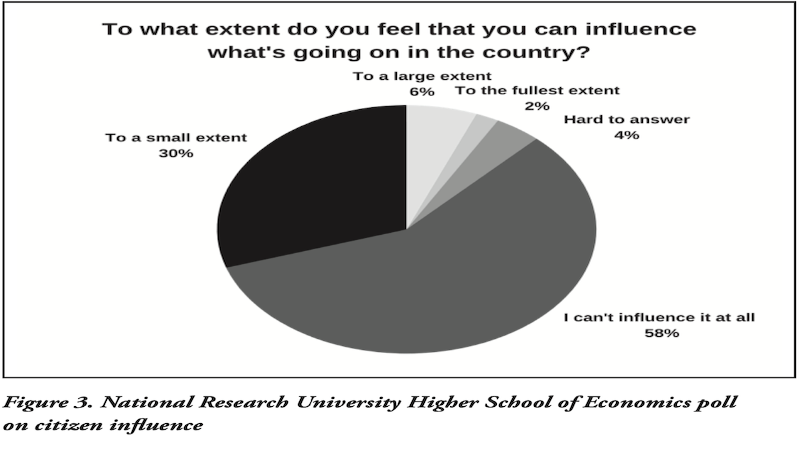

At the same time, more than 80 percent of respondents said that they felt they had little or no influence over the country’s affairs (Figure 3).40 However, the authors found a positive correlation between citizen partici- pation in civil society practices and an increased sense of civic responsibility at the local, regional, and federal levels.41 These findings prove that patterns of civic apathy can be changed, despite the fact that the majority of Russian society supports state paternalism and has a weak sense of civic responsi- bility. If citizens get involved in NGO activities, then they will develop civic responsibility. But the “foreign agents” legislation significantly curtails

opportunities for civic engagement in the first place, thus making such an objective effectively impossible to achieve at the moment.

But, another study provides for cautious optimism for the potential development of Russian civil society through public initiatives.42 It demon- strates that the number of young people under twenty-five who prioritize human rights is almost twice as high as those who prioritize the interests of the state.43 This finding is also supported by a 2017 Levada Center poll of young people, which found that only 27 percent of those surveyed said that they could not get by without government support, compared to 70 percent of the older age group.44

The generation of young Russians demonstrates high potential for civic engagement and, compared to the older generation, shares demo- cratic values to a much greater extent. However, the “foreign agents” law significantly curtails opportunities for citizens to exercise these beliefs, thereby eroding potential civic and political freedom, which is a necessary condition for sustainable development.

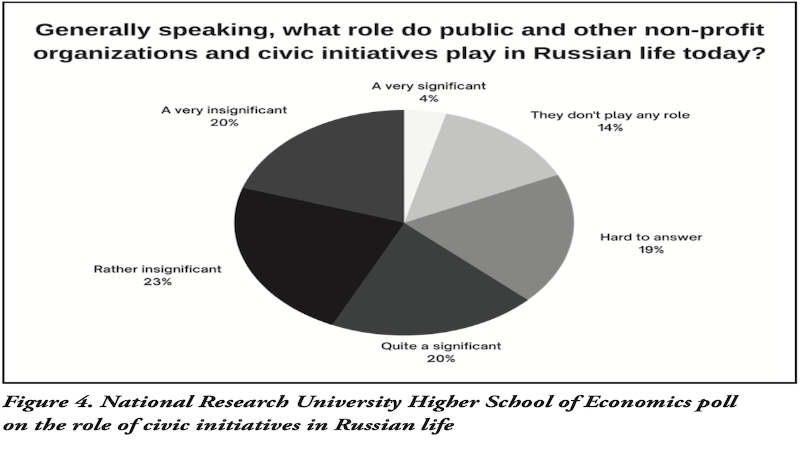

Stigmatization of Russian civic activism in general and NGOs in particular is especially dangerous in light of the current distrust of public organizations and the absence of a sustainable tradition of civic self-orga-nization. The results of sociological surveys show that people are skeptical about the role that NGOs and civic initiatives play in social life, with the majority of respondents considering it insignificant (Figure 4).45 Moreover, respondents to a 2014 Levada Center survey affirmed that the effectiveness of the public’s ability to influence civic initiatives is negligible, leading the survey authors to conclude that among the population there is “a wide- spread feeling of helplessness, loneliness, and inability to manage their own lives.”46

The emergence of “foreign agents” laws and their implementation has further exacerbated the already precarious condition of NGOs, significantly inhibited the development of civil society, and seriously undermined the Russian people’s free and sustainable agency. Indeed, government checks on NGOs to ensure compliance with “foreign agents” laws coupled with smear campaigns have launched the process of “deinstitutionalization of the public sphere – some organizations are liquidated, others are busy with endless reporting instead of meaningful work, [and] new activists (seeing these overwhelming bureaucratic costs) refuse to create officially registered structures.”47 Moreover, the nonprofit sector is “slowly being pushed into the shadows,” and the effectiveness of public work is also being dimin-

ished.48 Researches have assessed this trend as “carrying the risk of reducing the credibility of public organizations and initiatives in the public’s eye, as well as the potential for citizens to solve existing social problems.”49

A decade after the initial application of the “foreign agents” law in 2012 and a year into the Russian war in Ukraine and its accompanying propaganda, the results of the latest public opinion polls show a gradual growth of negative attitudes toward “foreign agents.” Sociologists from the Levada Center point out that although the Russian public does not share a unanimous attitude toward the law, the largest share of respondents (45 percent) believe that the meaning of the law on “foreign agents” is “to limit the negative influence of the West on the country,” while only a year ago 36 percent of respondents agreed with the statement.50 However, in the face of the consolidation of public opinion in support of the government and the deepening conflict with the West, they believe this proportion has increased.51 This trend is particularly troubling given the sharp increase in the activity of the Russian Ministry of Justice to populate the register of “foreign agents.” In 2021 and 2022, 298 organizations and individuals were added to the register, exceeding the 293 entries from the previous eight years combined.52

CONCLUSION

Today, the wheel of Russian history is taking another repressive turn, spinning against the Russian public just as it did at the beginning of the 20th century.53 By adopting the “foreign agents” laws, Russian authorities have given the executive branch unlimited power and turned the rule of law into a fiction. The temptation to indefinitely use the law as a means of suppressing dissenters is too great, especially in the context of a full- scale military conflict. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Russian civil society organizations were able to involve more and more people in their work, but this momentum was quickly quashed by the state as soon as people began exercising their right to peaceful protest. With the propagation of “foreign agents” laws and the war in Ukraine, there is no longer room for sustainable development. Just as they were a century ago, Russian authori- ties today are pathologically suspicious of any independent public initia- tives and any signs of liberal thought.

That being said, fatalism about the doomed nature of Russian civil society is not entirely fair. History shows that Russian society has the poten- tial for free and sustainable agency, but until the Russian people understand that they have the right to freedom of speech and free and fair elections,

and that the government must be accountable to its people, change will not occur. The strength of Putin’s authoritarianism lies in the weak civil consciousness of the Russian people. The question then becomes: how can the Russian population be made to understand the potential for genuine citizenship, self-consolidation, and horizontal cooperation? f

ENDNOTES

- 1 Vladimir Putin, “President’s Address to the Federal Assembly,” (speech, Moscow, Russia, February 21, 2023), President of the Russian Federation, http://kremlin.ru/ events/president/news/70565.

- 2 Vladimir Putin, “Meeting on Measures of Social and Economic Support for the Regions,” (speech, Moscow, Russia, March 16, 2022), President of the Russian Federation, http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67996.

- 3 Pavel Romanov et al., “Foreign agents’ in the field of social policy research: The demise of civil liberties and academic freedom in contemporary Russia,” Journal of European Social Policy 25, no. 4 (2015): 361.

- 4 Ibid.

- 5 Denis Volkov, Levada Center, Perspectives on Civil Society in Russia, June 13, 2011,https://www.levada.ru/2011/06/13/perspektivy-grazhdanskogo-obshhestva-v-rossii-2011-2/.

- 6 Ibid.

- 7 Ibid.

- 8 Amnesty International, Press Release, February 24, 2014, “Russia: Guilty verdictin Bolotnaya case — injustice at its most obvious,” https://www.amnesty.org/en/ latest/press-release/2014/02/russia-guilty-verdict-bolotnaya-case-injustice-its-most- obvious/.

- 9 Federal Law No. 121-FZ on Amending Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation Regarding Regulating Activities of Noncommercial Organizations Performing Functions of a Foreign Agent, July 20, 2012, http://www.consultant.ru/document/ cons_doc_LAW_132900/.

- 10 The Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, Pub. L. No. 75-583, 52 Stat. 631 (1938).

- 11 “Russia: Reject Proposed Changes to Rules on Foreign-Funded NGOs,” Human Rights Watch, July 13, 2012, https://www.hrw.org/news/2012/07/13/russia-reject- proposed-changes-rules-foreign-funded-ngos.

- 12 Tatiana Vorozheykina, Levada Center, Press Release, October 22, 2012, “How to Understand the Word ‘Foreign Agent,’” https://www.levada.ru/2012/10/22/kak- ponimat-slovo-inostrannyj-agent-kommentarij-t-vorozhejkinoj/.

- 13 Maria Tysiachniouk et al., “Civil Society under the Law ‘On Foreign Agents:’ NGO Strategies and Network Transformation,” Europe-Asia Studies 70, no.1 (2018): 621.

- 14 Polina Malkova, “Images and perceptions of human rights defenders in Russia: An examination of public opinion in the age of the ‘Foreign Agent’ Law,” Journal of Human Rights 19, no. 2 (March 2020): 205 and “Lawfare to destroy ‘enemies within’ – Russian NGOs tagged as ‘foreign agents,’” Amnesty International, October 9, 2014, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2014/10/lawfare-destroy-enemies-within- russian-ngos-tagged-foreign-agents/.

- 15 Federal Law No. 426-FZ on Amendments to the Law of the Russian Federation On Mass Media and the Federal Law On Information, Information Technologies and Information Protection, December 2, 2019, http://www.consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_LAW_339109/.

- Federal Law No. 481-FZ on Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of the RussianFederation in Part of Establishing Additional Measures to Counter Threats to National Security, December 30, 2020, http://www.consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_ LAW_372648/.

- 17 E.g. “The Ministry of Justice Recognized Six People and an NGO as ‘Foreign Agents,’” Foreign Agents (blog), OVD-News, April 8, 2022, https://ovd.news/express- news/2022/04/08/minyust-priznal-inoagentami-shest-chelovek-i-odnu-nko and “The Ministry of Justice Recognized Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Garry Kasparov as ‘Foreign Agents,’” Foreign Agents (blog), OVD-News, March 20, 2022, https://ovd. news/express-news/2022/05/20/minyust-priznal-mihaila-hodorkovskogo-i-garri- kasparova-inoagentami.

- 18 “Russia: Court order to liquidate Moscow Helsinki Group human rights organization unlawful,” Amnesty International, January 26, 2023, https://www.amnesty.org/en/ latest/news/2023/01/russia-court-order-to-liquidate-moscow-helsinki-group-human- rights-organization-unlawful/.

- 19 Ecodefence and Others v. Russia, Application number 9988/13 and 60 others, European Court of Human Rights, June 14, 2022, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/fre?i=001- 217751.

- 20 Federal Law No. 255-FZ on the Control of Activities of Persons under Foreign Influence, July 14, 2022, http://www.consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_LAW_421788/.

- 21 See Venice Commission of the Council of Europe, Rule of Law Checklist, adopted by the Venice Commission at its 106th Plenary Session (Venice, March 11-12, 2016), https://www.venice.coe.int/images/SITE%20IMAGES/Publications/Rule_of_Law_ Check_List.pdf.

- 22 Federal Law No. 255-FZ on the Control of Activities of Persons under Foreign Influence, Art. 2(1).

- 23 Ibid., Art. 22(2).

- 24 Ksenia Veretennikova, “Foreign agents denied liberalization,” Kommersant, June 22,2022, https://www.kommersant.ru/amp/5423940?fbclid=IwAR1jl24Ze_3FuuoJ0eJppnIGK0QVBjYI8139Z2fz951GLq9bspsynGu0g_8.

- 25 “You, Foreign Agent, are a dog: Deputies explain the new law to us. We yell andcall a lawyer,” July 4, 2022, Hello, you are a foreign agent, produced by Sonya Groysman, podcast, MP3 audio, 16:00 – 23:20, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/ podcast/%D1%82%D1%8B-%D0%B6-%D1%81%D0%BE%D0%B1%D0%B 0%D0%BA%D0%B0-%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B0%D0%B3%D0 %B5%D0%BD%D1%82-%D0%B4%D0%B5%D0%BF%D1%83%D1%82%- D0%B0%D1%82%D1%8B-%D0%BE%D0%B1%D1%8A%D1%8F%D1%8 1%D0%BD%D1%8F%D1%8E%D1%82-%D0%BD%D0%B0%D0%BC- %D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B2%D1%8B%D0%B9- %D0%B7%D0%B0%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%BD/ id1579350554?i=1000568744078.

- 26 Yong-Shik Lee, Law and Development: Theory and Practice (New York: Routledge Press, 2019), xv.

- 27 Ibid, 4.

- 28 Amartya Sen, Development as Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 3.

- 29 Ibid, 4.

- 30 Ibid, 18.

- 31 Ibid, 4.

- Pavel Romanov et al., “Foreign agents’ in the field of social policy research: The demise of civil liberties and academic freedom in contemporary Russia,” 363; Maria Tysiachniouk et al., “Civil Society under the Law ‘On Foreign Agents:’ NGO Strategies and Network Transformation,” Europe-Asia Studies 70, no.1 (2018): 625; Polina Malkova, “Images and perceptions of human rights defenders in Russia: An examination of public opinion in the age of the ‘Foreign Agent’ Law,” 205; Galina Goncharenko et al., “Disciplining Human Rights Organisations through an Accounting Regulation: A Case of the ‘Foreign Agents’ Law in Russia,” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 72 (Fall 2020): 7.

- 33 UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Press Release, December 14, 2021, “Russia: Dissolution of human rights organisations could start civil society shut down – UN expert,” https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2022/01/russia- dissolution-human-rights-organisations-could-start-civil-society-shut.

- 34 Levada Center, Annual Report: Public Opinion – 2011, https://www.levada.ru/sites/ default/files/levada_2011_0.pdf, 38.

- 35 Ibid, 40.

- 36 Levada Center, Annual Report: Public Opinion – 2021, https://www.levada.ru/cp/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/OM-2021.pdf, 47.

- 37 Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1994).

- 38 Levada Center, Annual Report: Public Opinion – 2021, 38.

- 39 I. V. Mersyanova et al., Moscow National Research University Higher Schoolof Economics, Series Monitoring of Civil Society: Charity and Participation of Russians in Civil Society Practices: Regional Dimension, 2013, https://www.hse.ru/ data/2014/03/23/1318318359/выпуск-8-сайт.pdf, 79.

- 40 Ibid, 100.

- 41 Ibid, 87.

- 42 Levada Center, Civil Activism of Russia’s Youth, October 1, 2020, https://www.levada.ru/2020/10/01/grazhdanskij-aktivizm-rossijskoj-molodezhi/.

- 43 Ibid, 1.

- 44 Denis Volkov, “A Generation of the Tolerant and Independent,” Gazeta.ru, June 19, 2017, https://www.gazeta.ru/comments/2017/06/15_a_10722443.shtml#page5.

- 45 I.V. Mersyanova et al., Moscow National Research University Higher School ofEconomics, Public Activity of the Population and Citizens’ Perception of the Conditionsfor the Development of Civil Society, 2007, https://grans.hse.ru/monograph, 59.

- 46 Denis Volkov et al, Levada Center, The Potential of Civic Participation in Solving Social Problems, November 18, 2014, https://www.levada.ru/2014/11/18/potentsial-grazhdanskogo-uchastiya-v-reshenii-sotsialnyh-problem-2014/. P. 51-52.

- 47 Ibid, 52.

- 48 Ibid.

- 49 Ibid.

- 50 Levada Center, Press Release, January 16, 2023, “Public Perception of ‘ForeignAgents,” https://www.levada.ru/2023/01/16/massovoe-vospriyatie-inostrannyh-agentov/.

- 51 Ibid.

- 52 “Features of Media Consumption in Russia,” Re-Russia.net, January 19, 2023, https:// re-russia.net/review/163/.

- 53 Anastasia S. Tumanova, Public Organizations in Russia: Legal Status: 1860-1930s (Moscow: Prospect, 2019).

(This post is republished from The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs.)