The Overwhelmed Brain: Attending To Your Own Well-Being

Last month, Dr. Mays Imad, nationally renowned neuroscientist, author, and Founding Coordinator of the Teaching and Learning Center at Pima Community College in Arizona gave a talk to members of the Tufts community. The title of her talk was “Bearing Witness as an Act of Love, Resistance, and Healing.” This talk was attended by faculty from the undergraduate, graduate and professional schools, staff from many university offices, board members, admissions personnel, and members of the University Development Office.

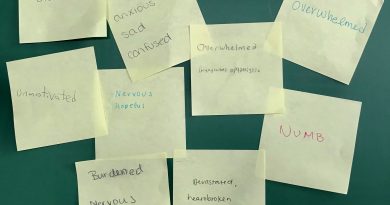

Dr. Imad began her talk with two essential questions: “What does it mean to be human in the aftermath of violence, oppression, and collective trauma?” and “How can we continue to move forward and serve others while attending to our own well-being?” During her talk, Dr. Imad normalized our emotional responses to the layers of stress that the pandemic, racism, and the climate crisis collectively have added to our lives and that has left many of us with sorrowful hearts and foggy brains. “We have been and continue to be in uncharted territory,” Dr. Imad suggests that these stressors, in the aggregate, overwhelm the brain in ways that leave us and our students feeling exhausted, disconnected, and disenchanted.

Dr. Imad contends that there are four states of being that have exacerbated our sense of dis-ease and distress:

- Social isolation. This is extremely stressful for the brain. Moreover, when we are in public spaces we pull away from each other out of fear and protective instinct. Although this may have eased since the vaccination became available, moving through public spaces reinforced our sense of isolation. Dr. Imad referenced experiences of social disengagement in public spaces. She asked us to reflect on experiences of averting one’s gaze or turning away physically from people we encountered at the supermarket in those early months of the pandemic. How many of you felt anxious going into any public space for fear of contracting the virus? This hypervigilance exacts a toll on the brain and our physiology.

- Less movement. We are not meant to sit for endless hours in front of a computer. We are meant to physically move and the lack of this can cause problems with sleep, digestion, and mood.

- Loss of control. Our brains need to have some perception that we are in control of our lives and that life is not entirely a function of chance. In the absence of this perception of control, the brain becomes overwhelmed and our sense of stress is amplified. While might argue that we have little control over much that occurs in life, having some perception of control and self-agency is critical to our managing stress and to keep our nervous systems from becoming flooded with cortisol that stimulates a fight or flight response.

- Loss of sense of coherence. This refers to having a sense of purpose in one’s life, that life has significance and matters, one believes in one’s own capacity to manage life stressors, and that the world makes some sense (Antonovsky, 1979). Janoff-Bulman (1992) refers to this as having an assumptive world where one believes in one’s own capacities and the fundamental goodness of others.

Coping and Well-Being Through Community

Dr. Imad suggests that a way to combat persistent traumatic stress is to “center the collective” and think of others, which is something we are neurologically wired to do, but not socialized to do. Quoting Palestinian poet, Mahmoud Darwish, “I wish I were a candle in the darkness,” Dr. Imad proposes that we can be candles for each other during dark and uncertain times.

Coming together to learn, to grieve, to play, to engage in social action, and to give voice to the voiceless can mitigate the deleterious biopsychosocial effects of chronic and persistent traumatic stress and create hope, meaning, and ultimately healing. These acts of communal coping, comforting, and healing, when possible, can help restore or maintain sense of coherence.

Strategies for Being a Candle in the Darkness For Yourself and Others

- Be gentle with yourself – you have good reason to be distracted and to struggle to get out of bed some days. Show this compassion to your colleagues and your students as well.

- Move, move and move some more. Create boundaries around work and take time to go for a walk, to be outside, and to exercise each day. Even as the days get shorter and darker, give yourself a break from work and screens.

- Try to limit zoom meetings in order to create breaks from screen exposure. Shorten meetings by a few minutes so you are not going to consecutive meetings without time to move, eat, or rest your eyes and mind.

- Hydrate and try to eat healthier.

- Make plans to connect with people. Attend campus events or events in the communities where you live and/or worship.

- Practice gratitude every day. Try to find one or two things for which you feel gratitude every day. There is significant evidence that doing this can change your mood, lessen the severity of anxiety and depression, and improve physical health.

- Continue to show your students compassion and flexibility. Check in to see how they are doing. You will not be compromising the integrity of the course, but making it a humane and inclusive experience.

Rutter (1993) maintained that the methods to cope are less important than the attempts unless the methods are self-defeating or self-injurious. Therefore, whether you try all of these suggestions, some of them, or none of them, central to maintaining sense of coherence and the restoration of emotional energy, resilience, and hope is the effort to cope.

Be a candle in the darkness, and by doing thus, you will find that others become candles that provide light and warmth for you in your darkness. Dr. Imad referenced a book of conversations between the Dalai Lama and the Archbishop Desmond Tutu in which the latter said, “We have hardships without becoming hard. We have heartbreak without being broken.”

References

- Antonovsky, A. (1979). Health, stress, and coping: New perspectives on mental and physical well-being. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.

- Darwish, Mahmoud. “Think Of Others.” Palestine Advocacy Project (blog). Accessed November 17, 2021. https://www.palestineadvocacyproject.org/poetry-campaign/think-of-others/.

- Imad, Mays. “Pedagogy of Healing: Bearing Witness to Trauma and Resilience.” Inside Higher Ed, July 8, 2021. https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2021/07/08/how-faculty-can-support-college-students%E2%80%99-mental-health-fall-opinion.

- Imad, Mays. “Hope Still Matters.” Inside Higher Ed, March 17, 2021. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2021/03/17/how-faculty-can-impart-hope-students-when-feeling-hope-depleted-themselves-opinion.

- Janoff-Bulman, R. (1992). Shattered Assumptions: Towards a new psychology of trauma. New York: Free Press.

- Lama, D., & Tutu, D. (2016). The book of joy: Lasting happiness in a changing world. New York: Avery Books.

- Rutter, M. (1993). Resilience: Some conceptual considerations. Journal of Adolescent Health, 14,626-632.

- Suttie, Jill. “Why Taking Care of Your Own Well-Being Helps Others.” Greater Good. Accessed November 17, 2021. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/why_taking_care_of_your_own_well_being_helps_others.