The Dangerous Allure of Win-Win Strategies – 11-12-2020

Excerpt from “The Dangerous Allure of Win-Win Strategies”, By Kenneth P. Pucker & Andrew A. King

Published in Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter 2021

Strategies for business-led “win-win” solutions to social and environmental problems—in which companies can promote social good and profit thereby— have gained wide appeal. Associated terms such as “shared value,” “circular economy,” “base of the pyramid,” and “reverse innovation” now pepper corporate reports and foundation websites. Corporate leaders, such as the members of the Business Roundtable, propose that they can simultaneously advance both profit and purpose. Famous academics contend that capitalism itself can be reinvented. The coauthors of this article have a long association with several of these so-called win-win ideas. One, Andrew King, is an engineer turned academic who studies the economics of pollution prevention. The other, Ken Pucker, is the former chief operating officer of Timberland, who worked for 15 years to demonstrate the value of a business model committed to “commerce and justice.” Given our backgrounds, one would think that we would find the present popularity of win-win strategies heartening.

Instead, we are alarmed. We know that these strategies rely on improbable mechanisms, promise implausible outcomes, and boast effectiveness that outstrips available evidence. We believe that they also inflict harm because they distract the business world and society from making the difficult choices needed to address pressing social and environmental issues. Their shiny appeal distracts us from adopting more effective strategies whose costs require careful weighing.

FROM HERESY TO DOGMA

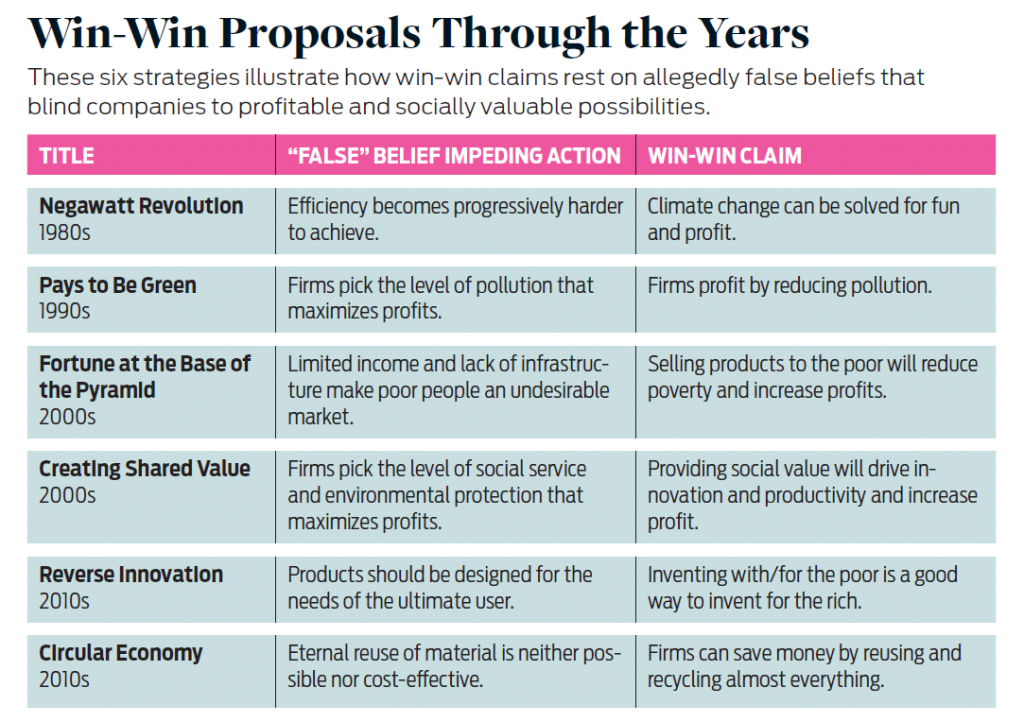

An exhaustive catalog of win-win strategies is beyond the scope of this essay. To give a sense of their breadth, ambition, and influence, we focus instead on six prominent examples. (See “Win-Win Proposals Through the Years” [below].)

The earliest idea of the group, the negawatt revolution, was proposed by Amory Lovins, a University of Oxford-trained physicist who in 1982 founded Rocky Mountain Institute, a US-based research organization dedicated to sustainability and energy efficiency. Lovins argued that companies were so inefficient that profits could be made by investing in energy-use reduction. As a result, firms could “solve climate change for fun and profit,” he promised.

Not long after, Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter and researcher Claas van der Linde formulated the “pays to be green” approach. They held that firms were so profligate in their use of resources that simple operational changes could allow those companies to be both “green and competitive.” Andrew King identified case examples that encouraged this contention.

In the aughts, business professor C. K. Prahalad suggested the “fortune at the base of the pyramid” strategy. He claimed that firms had so neglected the world’s poorest people that they could make enormous profits from those at the “base of the pyramid” (BOP), while also lifting people out of poverty. Business professor Vijay Govindarajan extended this idea in the following decade by proposing the strategy of reverse innovation: He maintained that the innovative potential of BOP markets had been overlooked; if those markets were tapped, he contended, valuable innovations would flow from poor to rich nations, engendering both profitable products and green solutions.

Michael Porter added another win-win proposal in the aughts, this time with consultant Mark Kramer, under the rubric of creating shared value. They argued that firms had neglected the profit potential of both social and environmental improvement. They also denied that conflicts between private and public objectives are common and encouraged managers to emphasize efforts that created “shared value”—i.e., value for both shareholders and stakeholders. Doing so, they claimed, would “drive the next wave of innovation and productivity growth in the global economy.”

Sixth, and finally, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation has synthesized several ideas for social and environmental betterment in recent years as the basis for a circular economy strategy. The foundation believes that firms can save money by reusing and recycling nearly everything.

The influence of these ideas is hard to overstate. They have reached the world’s biggest companies, informed White House strategy, shifted lobbying, and shaped international policy. Inspired by notions of profitable energy saving and poverty alleviation, Jeff Immelt, CEO of General Electric, created the “ecomagination” program in 2005. He designed it to engineer products and services that would save energy and lift people out of poverty—all while delivering superior returns to GE shareholders. In the following dozen years, Walmart, Nestlé, and Enel all announced that they were pursuing “shared value” initiatives.

In October 1993, President Bill Clinton unveiled his Climate Change Action Plan, which leaned on voluntary programs to help firms profitably reduce energy use and toxic emissions and design more efficient products. President Barack Obama’s November 2016 Climate Action Plan assumed that 20 percent of proposed CO2 reductions could be accomplished through “cost-effective energy efficiency.”

The International Finance Corporation has initiated several BOP projects in the past decade, and some policy advocacy groups, such as the Environmental Defense Fund and Greenpeace, have shifted their emphasis from promoting regulation to forming alliances with companies to promote win-win ideas. The idea that firms could profit by solving social and environmental problems went, as business and sustainability scholar Andrew Hoffman observed, “from heresy to dogma.”

About the Authors

KENNETH P. PUCKER (@kpucker31) is a senior lecturer at The Fletcher School at Tufts University, a lecturer at Boston University’s Questrom School of Business, and an advisory director at Berkshire Partners. He worked at Timberland for 15 years, including 7 years as chief operating officer.

ANDREW A. KING is a professor at Boston University’s Questrom School of Business. Over 25 years, he developed methods to test whether and when firms can profitably reduce their impact on the environment. With students and colleagues, he founded the Alliance for Research on Corporate Sustainability