Global Research Fellowship: Entrepreneurship in Nunavik – A new way of sharing?

by Nathan Cohen-Fournier (MIB 2017)

To share: to allow someone to use or enjoy something that one possesses. We can share what we possess in substance such as food or toys. We can also share immaterial matter such as time, memories, or affection. The meaning of words evolves along with the context and culture in which societies operate. That is to say the transformation is continual.

For the past 50 days, I have been conducting a research project on entrepreneurship in Nunavik, the northern portion of Québec. Inuit account for approximately 90% of the region’s 12 090 inhabitants and live in 14 villages connected solely by air and maritime transport, when possible.

When I first arrived, I was craving to discover spiritual bonds uniting native peoples with nature. I believe in the interconnectedness of life and matter. I was initially disappointed to discover a community in many ways similar to the ones “down south,” so clearly distinct from its surrounding environment. Maybe the spirituality I was looking for expressed itself in a way which I had not expected. I couldn’t force the discovery of what I wanted.

That’s when I started to realize the extent of sharing in modern Inuit culture.

The feeling of being at home in a host’s kitchen while serving yourself some boiling stew, the simplicity of a group eating raw arctic char in silence, a circle opening up with smiles as one joins for volleyball practice. These are just a few illustrations of the sharing I’ve experienced here. According to food surveys, I’m not the first one, as 99% of households in Nunavik receive country food from others (caribou, fish, beluga, seal, etc.).

As a matter of fact, over thousands of years, Inuit society “customarily functioned essentially on reciprocal solidarity” (Gombay, 2009) or a kind of collective insurance policy. As the harvesting of country food is known to be highly volatile, sharing was synonymous with survival.

In conducting interviews, I inquired about the changes brought on by economic development and the perspectives towards it. Interestingly, according to many participants, one of the major transformations related to sharing. One contributor, a well-known female artist, says: “They [community members] are starting to buy country food. They used to help each other. It’s less there. It’s a big erasing, helping each other. It’s going away”.

Another participant, who is currently in office for region-wide economic development, answers: “[Entrepreneurship] is a foreign concept. Traditionally, we were taught to share. I was never taught to, let’s say, use whatever I catch from the land to sell it and earn money. But then again, I don’t take offense from anybody who does that. For many, it’s their only source of income.”

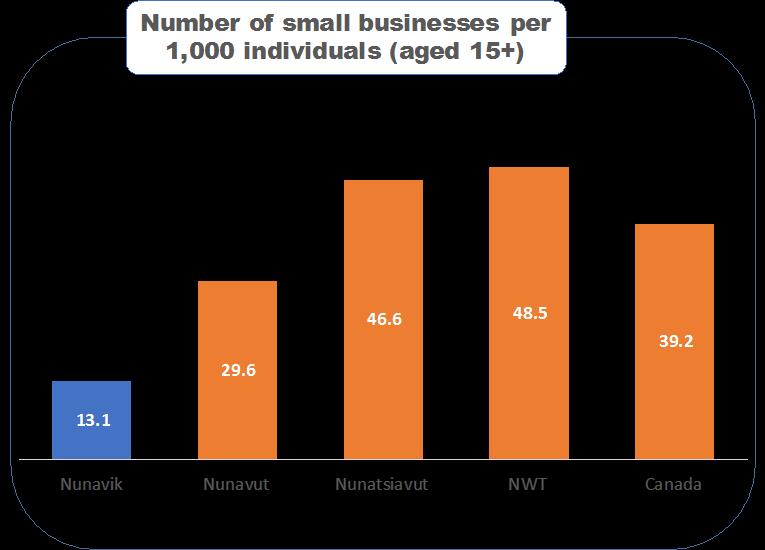

This perception on business certainly translates into figures. As we can see in the graph below, Nunavik is the region in Canada where businesses are scarcest. This can be explained by a number of factors, including remoteness and high operating costs. Nevertheless, the other regions analyzed (Nunavut, Nunatsiavut, and the Northwest Territories) share similar characteristics. We can therefore make the assumption that the notion of individualism, which so often characterizes small businesses, does not dominate the economic logic in Nunavik. To most, the idea of capital accumulation for the prospect of one single individual or group is rejected. As a result, a high proportion of the entrepreneurs I have met with feel “marginalized” despite their best efforts to improve well-being and job opportunities.

Is the sharing economy that is so prevalent in Nunavik irreconcilable with the emerging market economy? And by sharing economy, I’m certainly not referring to the Ubers and AirBnBs of this world. Has the word “sharing” reached a point where it relates to selling unused capacity, whether it be time, real estate, or anything else? I hope not.

Surely, there must be a path to harness the collaborative spirit inherent to Northern communities while also improving collective well-being in a self-sustained way. Air Inuit and the FCNQ, which owns the 14 co-operative stores across Nunavik, are valid examples. These businesses are collectively owned and generate hundreds of millions of dollars, while providing a sense of pride and self-reliance to the region. However, the FCNQ was created in 1967 and Air Inuit in 1978.

Where is the new wave of collective businesses that have the potential to empower future generations and create a brighter future of Nunavimiut?

Where is the new wave of collective businesses that have the potential to empower future generations and create a brighter future of Nunavimiut?

I have met with creative artists, hard-working mechanics, and innovative graphic designers. Each day is a new struggle. In order to thrive, support networks between businesses across the region will be essential. By regrouping, they will be able to bring down costs such as insurance and create a viable supply chain in the territory. Sharing in the Arctic is more than generosity, it’s survival.

Nathan Cohen-Fournier is a Master of International Business candidate at The Fletcher School. This project was undertaken as part of the Global Research Fellowship through the Institute for Business in the Global Context. You learn more about the Fellowship at its website.