Student Case Study: It’s (Not) All About the Money: Mobile Money and Innovation at BRAC

by Jessica Meckler (MALD 2016), under the supervision of Prof. Kim Wilson, CEME Senior Fellow, and with the support of Maria May, BRAC

The following is the executive summary of a case study examining mobile money and innovation. Read the full case study here.

In 2007, M-PESA, a mobile payment service for the unbanked, was launched in Kenya. Within the first month, over 20,000 M-PESA clients registered for the service. This interest indicated an unexplored area with great potential in the field of financial services.[i] After M-PESA, digital financial services and mobile technology quickly gained popularity as a new, transparent, and efficient means to alleviate poverty. The benefits of mobile money seemed plentiful. They presented a means to circumvent the perennial issues of delivering financial products to poor communities in rural areas. Suddenly the geographic challenges of bad roads, inclement weather, and the high costs of maintaining operations in rural areas seemed to be approaching their end – in theory.

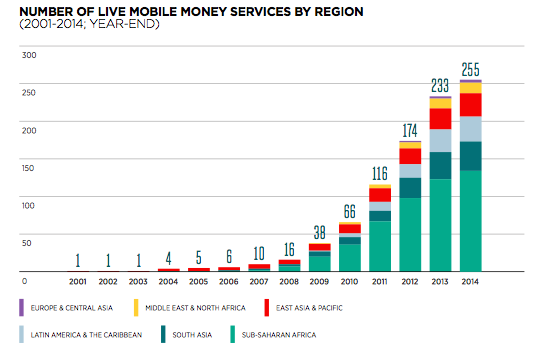

(Graph from the State of the Industry: Mobile Financial Services for the Unbanked 2014.)

In reality, the hype of mobile money fast exceeded proof of the effects of mobile money on the financial lives of the poor.[i] By 2013, mobile money services were available in most developing nations and emerging markets, with approximately 219 live mobile money services available in 84 countries worldwide.[ii] The arrival of mobile money in Bangladesh was inspired by the growth of mobile money in Kenya. Bangladesh’s prominent mobile money provider, bKash, was launched in 2011. By the end of 2013, bKash had registered 11 million accounts[iii]. The rapid growth of bKash led CGAP to estimate that bKash was the fastest growing mobile financial services business in 2013.[iv]

Rapid growth in Bangladesh, as elsewhere, posed many questions. What would spur faster adoption of mobile money payment options in place of cash in existing development projects? Projects and programs could be built around mobile money, but what would it take to successfully integrate mobile money into the existing systems of large development organizations? Could mobile money replace cash in programs designed to run efficiently with cash? What would it take to change the implementation, data collection, and financial models of these organizations? Understanding how the integration of mobile money services affects organizations is vital to the overall success of the technology in the development sector. Given the successful start of mobile money through bKash, Bangladesh is an ideal place to explore these questions of mobile money in development.

To answer these questions, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation joined forces with BRAC. BRAC is one of the world’s largest non-governmental organizations and a respected actor in the fight against poverty. Headquartered in Dhaka, Bangladesh, BRAC programs address the myriad aspects of poverty alleviation: education, health, microfinance, legal and human rights, gender, and disaster relief. In September 2013, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provided BRAC’s Social Innovation Lab (SIL) with a three-year grant of $2.6 million to create an Innovation Fund for Mobile Money. The goal of the Innovation Fund was triple-fold:

- Increase the adoption of digital financial services at BRAC, particularly in service delivery;

- Increase the adoption of digital financial services by BRAC clients; and

- Contribute to the global discourse on digital financial services.

Within the first year of the grant, SIL had uncovered a number of hurdles that organizations must address before mobile money can be integrated successfully into existing programs. Large organizations, especially well-established ones like BRAC, designed their systems to operate with physical cash. Transitioning to digital cash required a great deal of inter-organizational communication and adjustment. Primary lessons that SIL learned were:

- The importance of stakeholder buy-in, both internal and external to the organization;

- Clear communication and goal-sharing with mobile money service providers; and

- The convenience of team members who can develop software targeted to program needs.

It was not an easy year. Despite the difficulties, the first year of the grant saw the start of seven mobile money pilot projects and an increasing interest in mobile money within BRAC operations. Even then, other questions – such as whether or not smaller organizations with less funding could handle the transition – remained. This case study covers the first year of the SIL’s mobile money projects. It is intended to serve as a learning tool to guide organizations that aim to incorporate mobile money into existing organizational structures.

Jessica Meckler is a 2016 Master of Law and Diplomacy candidate at The Fletcher School of Law & Diplomacy

Read the Full Case Study Online

[i] Lee, Jean. “A Roundup of Recent and Ongoing Mobile Money Research in Economics.” Financial Access Initiative. 7 November 2013. Accessed 28 March 2015.

[ii] Penicaud, Claire and Arunjay Katakam. “State of the Industry 2013: Mobile Financial Services for the Unbanked.” Mobile Money for the Unbanked. http://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/SOTIR_2013.pdf

[iii] Chen, Gregory and Stephen Rasmussen. “bKash Bangladesh: A Fast Start for Mobile Financial Services.” CGAP Brief. 29 July 2014. http://www.cgap.org/publications/bkash-bangladesh-fast-start-mobile-financial-services

[iv] Chen, Greg. “bKash Bangladesh: What Explains its Fast Start?” CGAP. 4 August 2014. Accessed 23 May 2015. http://www.cgap.org/blog/bkash-bangladesh-what-explains-its-fast-start

[i] Hughes, Nick, and Susie Lonie. “M-PESA: Mobile Money for the “Unbanked.” Turning Cellphones into 24-Hour Tellers in Kenya.” Innovations. Winter & spring 2007. Accessed 28 March 2015. http://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/innovationsarticleonmpesa_0_d_14.pdf