As I was scrolling through some news articles about museums on my phone, I came across an interesting article about how the Musée Rodin in Paris is using revenue from the sale of bronze casts of Auguste Rodin’s sculptures in order to decrease their budget deficit due to the pandemic. I was not previously aware of the museum’s decision from two years ago to dramatically increase the number of works that can be cast, a decision that is clearly benefitting the museum now. Initially, it seems strange to allow for the sculptures to be made again in bronze and sold to private collectors and other museums; however, this decision was allowed for in the institution’s bequest and Rodin himself stipulated that the museum has the rights to his works. This year, two large bronze pieces have been sold to a Middle Eastern museum, helping the Musée Rodin to lower their deficit to about three million euros. The institution has also set up an online donations page from which they have received 1,200 euros.

What efforts have other museums made to decrease their financial burdens? The Museum of the City of New York is discussing launching virtual adult education courses that might include online discussions moderated by curators that are focused on New York topics. The museum is also putting the online programming it has released during the pandemic to good use: it has collected over 4,000 photographs and “Covid Stories” documenting New York’s experience of the pandemic and curators are now preparing an exhibition for the fall centered on this topic (using a previous 2018 exhibition focused on past epidemics in the city, titled “Germ City” as a model).

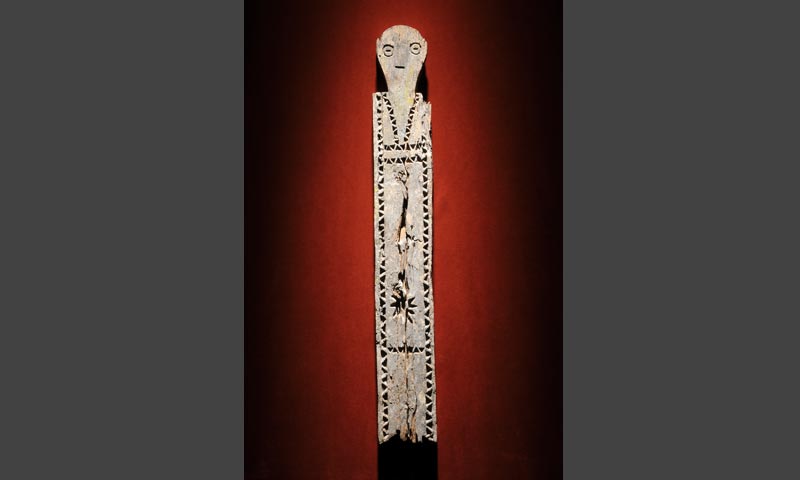

Jacob A. (Jacob August) Riis (1849-1914). [Infirmary.] ca. 1890. Museum of the City of New York 90.13.2.322.

Meanwhile, the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation in Germany is aiming to restructure the extensive bureaucracy within the foundation and perhaps even dissolve and replace it with a new foundation to manage the state museums in a more streamlined and concise structure. This would also allow for more budget autonomy for each individual museum as well as restructuring financing in order to allow for improved long-term planning.

This is an extremely difficult time for all museums as they struggle to survive the economic hardships caused by the pandemic. Many institutions have had to furlough staff and cancel programming, and still some might not survive. However, it is encouraging to see the diverse and creative methods – and self-evaluation – that some institutions are employing in order to improve their economic prospects.